For starters, Paul Chaat Smith describes the reality of Native America before Columbus. From Exile on Main Street: Home of the Brave:

For starters, Paul Chaat Smith describes the reality of Native America before Columbus. From Exile on Main Street: Home of the Brave:

For starters, Paul Chaat Smith describes the reality of Native America before Columbus. From Exile on Main Street: Home of the Brave:

For starters, Paul Chaat Smith describes the reality of Native America before Columbus. From Exile on Main Street: Home of the Brave:

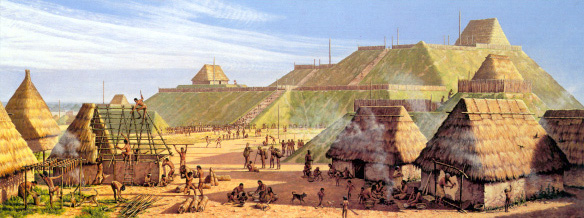

Five hundred years ago we were Seneca and Cree and Hopi and Kiowa, as different from each other as Norwegians are from Italians, or Egyptians from Zulus. One example of just how different is the splintering of languages. Greek and English and Russian all have the same Indo-European root. As different as those languages are, at one point they were very similar. In North America there were more than 140 such different language stocks. The Americas were a happening, cosmopolitan place, and when Europeans first showed up one suspects the reaction was less the astonished genuflection the explorers reported than something more like, "So, what's your story?" When we think of the old days like it or not we conjure up images that have little to do with real history. We never think of the great city of Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire, five centuries ago bigger than London. We never imagine sullen teenagers in some pre-Columbian Zona Rosa dive in that fabled Aztec metropolis, badmouthing the wretched war economy and the ridiculous human sacrifices that drove their empire. We don't think of the settled Indian farming towns in North America (far more typical than nomads roaming the Plains). We never think about the Cherokees, who built a modern, independent nation, with roads and schools and universities and diplomatic recognition from European countries. After Sequoyah invented the Cherokee alphabet, it took just over a year for the entire nation to become literate. The Cherokee were just as typical as the Sioux, but you don't hear much about them.

America pre-Columbus was a riot of vastly different cultures, who occasionally fought each other, no doubt sometimes viciously and for stupid reasons. If some Indian societies were ecological utopias with that perfect, elusive blend of democracy and individual freedom, some also practiced slavery, both before and after contact. And if things were complicated before the Admiral showed up, they got even more so later. For centuries North America was perhaps the most intricate geopolitical puzzle on earth, with constantly shifting alliances between, with and among Indians and Europeans. As Chuck Berry would say many years later, anything you want we got it right here. Yet the amazing variety of human civilization that existed five centuries ago has been replaced in the popular imagination by one image above all: the Plains Indians of the mid-19th century. Most Indians weren't anything like the Sioux or the Comanche, either the real ones or the Hollywood invention. The true story is simply too messy and complicated. And too threatening. The myth of noble savages, completely unable to cope with modern times goes down much easier. No matter that Indian societies consistently valued technology and when useful made it their own. The glory days of the Comanches, for example, were built on the European imports of horses and guns. (We mastered both and delayed the settlement of Texas a hundred and fifty years, a public service we're proud of to this day.)

This passage suggests a basic question: How and why did our view of Indians change from a diverse continent of thousands of tribes to a handful of nomadic tribes on the Plains? The answer is that Euro-Americans wanted to "tame" the continent, to make it theirs. So they had to come up with a justification for marginalizing or eliminating the continent's inhabitants.

In other words, the taming of America meant the taming of the Indians.

Gary Nash has written a superb essay, Red, White, and Black: The Origins of Racism in Colonial America, on this subject. In it, he describes how the colonists' opinion of Indians shifted over time. When the colonists needed them to stay alive or fight a war, the Indians were brave and noble savages. When the Indians got in the way and threatened Euro-American plans, they became heathens, devils, beasts in human form.

If the colonial era saw the first phase of Native stereotyping, the westward-expansion era saw the second phase. It was then that many of the basic stereotypes became rooted in the American mind.

Images spread through media

Once the colonists formed their impressions of Indians, these impressions spread far and wide. People who had never met an Indian, as the first settlers had, got their views from the media. An exhibit at the Huntington Library entitled "Legacy and Legend" explains the role of prints, posters, photographs, and books:

Not always drawn from life

Depictions of Native Americans often reflected what artists wanted to see, a Huntington display shows.

Most of the exhibition is devoted to material from the 19th century, when interest in Native Americans had a resurgence precipitated by the Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804, which sparked the westward expansion. Advancements in printing techniques, especially in lithography, made it possible for this round of images to be widely disseminated. And these depictions also helped feed a push by poets and writers for a national myth, says Hight. "They were looking for a long history rooted in the land, and Indians were part of that."

In the early half of the 1800s, four major portfolios featuring Indians' portraits and their way of life were produced, and Henry Huntington, whose collection and estate are the basis of the museum and library, managed to acquire three of them. (The fourth, by George Catlin, a master of Western genre drawings and paintings was acquired in the 1950s.) A larger gallery of the Boone displays selections from all four portfolios — some as original prints, some as enlarged reproductions — as well as the books that accompanied them.

Among the most famous artists is Catlin, who sketched and painted Native Americans in their home territories. Since "Legacy" focuses on prints and photographs — works that were seen by the masses — Catlin is represented here by both hand-colored lithographs sold to collectors and seven smaller reiterations produced by Currier & Ives to be sold to the middle class. Catlin was another self-promoter, says Hight, and he exaggerated the amount of time he spent in the West, as well as what he had seen.

Hight has also drawn from portraits done when the Native Americans went East, including a set commissioned by the U.S. government of Indian leaders who visited Washington, D.C. Though the original paintings were lost in an 1865 fire, hand-tinted lithographic versions had been made, and 17 of these are included in the exhibition. These portraits show a variety of facial features and tribal garb — Kee-She-Waa, a Fox warrior, wears a turban, and Push-Ma-Ta-Ha, a Chactan warrior, donned a European-style military uniform. And yet, by the end of the century, the Indians' image had been homogenized, becoming identified with the feathered war bonnet and the beaded breastplate, as in the 1907 Edward S. Curtis photograph "High Hawk."

A book review of The Newspaper Indian: Native American Identity in the Press, 1820-1890 explains the role of newspapers:

The book begins with a valuable introduction by the author that sets the tone for discovery in later chapters. Here he addresses Horace Greely in 1859, as the then-noted editor of the New York Tribune newspaper decides to go West. Greely, who had spent most of his life in the East and had never been West, delivered a strong perspective on American Indian people that was heavily influenced by a strong belief in the Bible and in American Christianity. Greely's perspective was that American Indians were uncivilized, had no work ethic, and were examples of the "lowest and rudest ages of human existence." He also believed that the more Christian American Indians became, the more civilized America would become. The significance of this perspective is that a very large mass audience in the East was anxiously waiting for Greely to write of his traveling experiences and first contact with American Indians as he headed West on this, his first excursion.

The introduction of this book is well laid out, well done, and very necessary. Strong historical accounts with some illuminating research are woven into the remaining chapters of Coward's book. Some of the strongest material addresses how American Indians became a part of the nineteenth century American mass media experience. One example is the inclusion of American Indians in Benjamin Harris's Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick, in 1690 the first newspaper printed in colonial America. Harris writes warnings about barbarous Indians lurking about Chelmsford and the disappearance of two children "both of which were thought to have fallen into the hands of the Indians." In another paragraph he praises Christianized Indians for their decision to worship God with a day of Thanksgiving. The accounts thus offer examples of two very different versions of American Indians, both identified as outsiders to the colony.

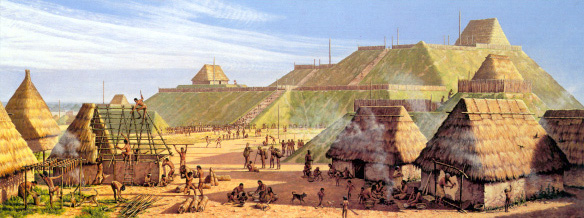

Coward goes on to explain with early newspaper accounts how American Indian identity began to fall into two very distinct areas: 1) American Indians were an apathetic but sometimes romantic people, and 2) American Indians were wild, bloodthirsty, cannibalistic savages willing to kill Caucasian people for whatever reason. According to the New Orleans Picayune newspaper in 1866, "we cannot open a paper from any of our exposed States or Territories, without reading frightful accounts of Indian massacres and Indian maraudings."

This book addresses and references some of the American Indian issues that those who research American Indians may have heard about and believed to be true, while lacking the verification of scholarly references or citations. One example and important contribution is how the press fabricated American Indian confrontations [End Page 673] with the U.S. Army. "Battles" became "massacres," if the Indians were able to defeat and push back U.S. Army attacks. Newspapers choosing words that would stir high emotions, stretch the fabric of truthful reporting, and create negative perceptions against American Indians and cause divisiveness are also examined in this book. Chapter four is an informative read on The Daily Rocky Mountain News and the scandal of Sand Creek. With over two hundred Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians killed by Col. John Chivington's men, The Daily Rocky Mountain News called the attack at Sand Creek "the most effective expedition against the Indians ever planned and carried out." The surprised and peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho thought they were under government protection by the very army that attacked and killed their women and children. In addition, some accounts given by Col. Chivington's own men after the massacre reported that nearly all the dead American Indian men, women, and children had been scalped or mutilated by Chivington's men.

Taming the "Wild West"

It's fairly well accepted these days that America's "Wild West" is a myth. Americans invented it to give context to their national icon, the cowboy. A book review in the LA Times, 4/4/04, hints how this happened:

Larry McMurtry, one of the few contemporary novelists who still write unapologetically about the Old West, once set himself the task of compiling a list of people "who had a hand in inventing the West." Tellingly, the list was far more expansive and eclectic than we might have expected, beginning with Thomas Jefferson and ending with Andy Warhol.

"In between came gunmakers, boot makers, saddlemakers, railroad magnates, painters, Indians, actors, directors, liars of many descriptions, but not, by golly, very many writers: only Ned Buntline, Zane Grey, Max Brand, and Louis L'Amour," McMurtry declares in "Sacagawea's Nickname," a collection of 12 essays that first appeared in the New York Review of Books.

.

.

.

McMurtry despairs of the vast gap between myth and reality in the depiction of the West in arts and letters as well as in popular culture. "[M]ost of the traditions which we associate with the American West," he insists, "were invented by pulp writers, poster artists, impresarios, and advertising men" — a complaint that casts his own work in an intriguing new light.

He points out that celebrated scout Kit Carson was transformed from a flesh-and-blood human being into an artifact of pop culture in his own lifetime. "[He] had become a dime-novel hero as early as 1847-1848," McMurtry writes. "Today it would be hard to scare up one hundred Americans who could say with any accuracy what Kit Carson actually did, and ninety-five of those would be Navajos, who remember with bitterness that in 1863 he evicted their great-grandparents from their homes and marched them to an unhealthy place called the Bosque Redondo, where many of them died."

Not only did Indians help invent our national mythology, but they were key players in it. Since we invented the cowboy to represent our best and brightest side, we needed the Indian to represent our deepest and darkest side. Once thought of as innocent children, Indians became the enemy we had to overcome to realize our potential—to manifest our destiny, one might say.

From "The Tonto Syndrome," Scholastic Update, 5/26/89:

Cowboys and Indians

Most non-Indians form their first impressions of Native Americans on the playground. "When little kids play cowboys and Indians," says Robert Thomas, of the University of Arizona, "the Indians are always the bad guys. The cowboys win, the Indians get defeated. Children learn that Indians are bad."

Such games, and the stories that inspire them, seek to reenact the conflict between Native Americans and the first white settlers, who arrived in this country in the early 1600s. The problem, say most scholars, is that they draw on a one-sided view of history. "From contact with the first European settlers, the people writing the books were the Europeans," says Duane Hall of the American Indian Institute at the University of Oklahoma. "There were very few Indian writers giving an Indian account of the story. Down through the pages of history, Indians became people without names and faces, people who are very stoic, and have no feelings."

Buffalo Bill's Wild West

The myth of the American Indian was further refined by frontiersman William Frederick Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill. In 1883, Cody formed Buffalo Bill's Wild West, a traveling show. The act included a mock battle with Indians, played, for the most part, by members of the Lakota Sioux tribe. Because Buffalo Bill's Wild West was as close as most Americans got to "real" Indians, Sioux traditions became, in the public mind, synonymous with all Indian customs.

By the time "Injuns" made it to the Western movies of the 1950s, directors generalized many Sioux traditions—such as hunting and feather headdresses—to all Indians. In fact, the hundreds of Native American tribes each have their own customs. The Hopi, for example, lived in villages, cultivated corn, and crafted elegant pottery.

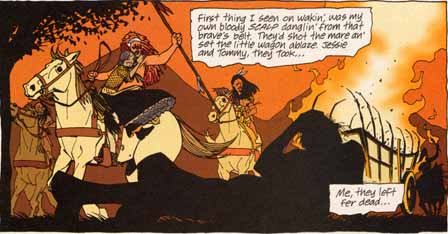

"The old movies rely on a homogenized Indian," says Karen Biestman of the University of California. "He is usually male, wears buckskin, beads, feathers, has a pinto pony, and is savage, uncaring, and brutal. But it's a shallow image. We don't see families, caring, a sense of community, spirituality, or day-to-day life."

And much of what we see is simply made up. "We rarely see women," says Biestman. "If we do, it's the princess, the daughter of a chief. But there's no such thing as royalty in Indian culture. These images are largely perpetuated by non-Indians. They are simply inventions."

Those inventions live on in the form of cigar-store Indians, and roadside attractions such as giant Indian statues, made-for-tourist totem poles, and "ceremonial" dance pageants. The Tomahawk Indian Store in Lupton, Arizona, for instance, looks like an enormous yellow brick teepee, but actually serves as an Indian craft gift-shop and restaurant.

A few small corrections to the Scholastic Update's essay:

The Wild West show

Buffalo Bill's Wild West show was perhaps the apotheosis of Native stereotyping. It showcased beliefs and attitudes also apparent in dime novels and later in Western movies. Therefore, it deserves a closer look. From a book review of Buffalo Bill's America by Louis S. Warren in the NY Times, 12/11/05:

Gunpowder entertainment and Indian wars were also at the heart of the Wild West show he invented and first took on the road in 1883. It offered everything Western that wide-eyed Easterners hoped to see except the landscape: horses, elk and buffaloes; roping, riding and sharpshooting; simulated cyclones and prairie fires and gun battles and (for one season only) Sitting Bull himself. Buffalo Bill was always in the thick of it. Mounted on a handsome gray horse, he swept his big hat from his head to introduce his "Congress of Rough Riders of the World"; shot glass balls from the air; galloped to the rescue of a stagecoach and a settler's cabin surrounded by whooping Indians; and took center stage for a deeply affecting -- and entirely imaginary -- tableau in which he arrived only moments too late to save Custer and his command from annihilation.

Warren explains how Cody and his collaborators, the shrewd showman Nate Salsbury and the brilliant publicist John Burke, figured out how to attract the middle-class family trade by packaging this crowded spectacle as a panorama of unbroken Western progress from wilderness to white settlement. " 'Buffalo Bill's Wild West' is not a show in the theatric sense of the term," the publicity said, "but an exposition of the progress of civilization." Cody could claim to edify and inspire as well as entertain. He gave Americans what they wanted to see, a fast-moving history of the West in which, as Richard White has written, "everything is inverted": Native Americans are the aggressors, their white conquerors the innocent, abused victims in need of rescue. Later, British and European audiences loved it, too.

More on the history of Native stereotypes

From the Baltimore Sun:

Challenging old views of the American Indian

Duality: Images accepted for 500 years are in question. A new Smithsonian museum could supply some answers.

By Michael Hill

Sun Staff

Originally published August 29, 2004

Close your eyes and conjure up what comes to mind when you hear the words "American Indian." No matter your political correctness, the dominant image is probably one of feathers and war paint, bows and arrows, buffalo and teepees, beads and skins, wisdom and warfare.

It is an image derived from adventure movies and childhood books, from sepia-tinged photographs and museum exhibitions, from exploitative television shows and earnest documentaries. Even recent publicity about Indian casinos cannot blemish its iconic power.

Whether the Indian in your image is villain or victim, it is likely some exotic "other," a more primal being somehow in touch with elemental nature which can be a source of savagery and spirituality.

Next month, the Smithsonian Institution -- which had as much to do with cementing the image of the Indian in the American mind as any institution -- opens its Museum of the American Indian, probably the last great museum to be built on the Mall in Washington. This $200 million facility, decades in the making, could go a long way toward challenging views of the American Indian developed since Europeans encountered these people in the 15th century.

"There really is a duality in the many, many images of the Native American over the last 500 years," says Rennard Strickland, an expert on Indian law at the University of Oregon. "It goes between what I call the 'savage sinner' and the 'red- skinned redeemer.' We tend to use the Indian as a mirror on which we reflect a lot of our own particular neuroses."

The duality can be seen in some of the earliest accounts: the noble friend who sat down for the first Thanksgiving dinner, the fool who sold Manhattan for $24 in beads, the enemy who kidnapped white women and raised them in savage ways.

"I think there has been a schizophrenia in the American perception of the Indian from the very beginning," says Orin Starn, an anthropologist at Duke University. "From very early on, there is this dual desire to, at the same time, on the one hand, exterminate them -- either kill or remove them to make way for the United States -- and to romanticize them, to admire them, to be like them.

"Go back to the Revolutionary War and the Boston Tea Party," he says. "Colonists there dressed up as Indians. There was this identification with being proud and wild and savage in rebelling against the British."

This continued, Starn says, in the 1800s, when U.S. troops were fighting Indians in the West. "You are fighting to defeat these people but at the same time you are fascinated by these people who ride bareback with eagle feather headdresses, who know how to hunt with a bow and arrow," he says.

Akim Reinhardt, a historian at Towson University, points out that Indians had a different role in the life of early colonists.

"Indians, from the initial settlements in the colonial period up through the 1700s and the beginning of the nation, represented something scary to the colonists," he says. "It now seems preordained that those 13 Colonies would persist, but it was not clear at the time. The Iroquois confederacy in the North, the Cherokee and Creek confederacy in the South were, in fact, much stronger than the early European colonies. So they had a very different perception of Indians than we do now."

Reinhardt points to the popularity of James Fenimore Cooper's Leatherstocking Tales and the widespread captive narratives -- some fraudulent, some true -- of people taken by Indians and later returned to white society, as evidence of the fear and fascination Indians represented to early settlers.

From the beginning, the settlers' attitudes toward the Indian were a mixture of avarice and altruism. Moving them out of the way to reservations was a way to get their land for expansion of the new country. But many also saw it as a way to protect these innocent people until they could be educated and brought up to the standards of Western civilization.

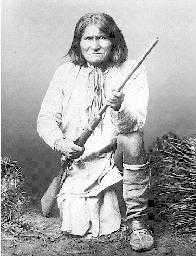

A change in the nation's view came about a century ago. Geronimo was captured in Mexico. The Battle of Wounded Knee ended the last Indian threat. Most thought their culture was on the verge of extinction. The romanticization began.

Buffalo Bill Cody had earlier put Indians on display in his Wild West Show. Others were seen in exhibitions at turn-of-the-century World's Fairs.

Edward Curtis began his photographic odyssey to document the cultures. Anthropologists and amateurs went about preserving a way of life that was seen as disappearing, a tragic, but inevitable byproduct of civilization. Many objects in the collection of the new museum were collected at this time.

Portrayal in movies

For the most part, this is the Indian culture that was put under glass in museums and declared "authentic." This is the one portrayed in movies, even if it meant -- as Strickland says in his 1997 book Tonto's Revenge -- putting Seminoles from Florida in headdresses from the Plains. Or in the case of many Curtis photographs -- as Reinhardt notes -- dressing subjects in inappropriate attire to make them more photogenic.

Ignored was the fact that the culture being documented and preserved was far from that of a pure indigenous people. The horse came from the Spanish. Beads came from Europeans.

Roger Nichols, a historian at the University of Arizona, says that these cultural transitions are rarely examined from the Indians' point of view.

"We tend to think they were ripped off in the fur trade, but they thought they were ripping off the traders," he says. "They were getting glass pots that were a lot better than the clay ones that would break every time you dropped one. ... "People tend to think of everything their ancestors did with the Europeans as negative, but the Indians didn't see it that way."

Starn examined one aspect of this era in Ishi's Brain: In Search of America's Last "Wild" Indian. The book documents the story of the last survivor of the Yahi tribe who was captured in California in 1911, handed over to an anthropologist and put on display in a museum until his death five years later. Starn tells of finding Ishi's brain preserved in the Smithsonian and eventually repatriating it to a California tribe.

"In the 1860s and '70s, Ishi's tribe was described as bloodthirsty redskins and killers," Starn says. "By the time he was captured, the Indians had been defeated on the battlefield and America was moving much more toward a frame of imperialist nostalgia.

"In the 1910s, the Indian tends to be viewed as a noble, primitive man in touch with nature, a master of the arts of hunting and fishing and making arrowheads, who knows the myths of his people," he says. "This was all disappearing. Ishi was viewed as the last of his kind, the last real Indian."

There was a problem with this romanticization of a disappearing culture: It failed to disappear.

"I think it was 100 years ago almost exactly that Edward Curtis took one of his most famous photographs," says Peter Iverson, a professor of history at Arizona State University. "It was of a group of Navahos riding into the distance. It was called The Vanishing Race.

"Today, there are more Navahos than there were Indians 100 years go. There's more Indian land. It has not turned out as many people anticipated."

The reservation system, which was supposed to protect Indians while getting them ready for civilization, became places where culture could be protected and, despite poverty and other social ills, preserved. The schools that were to raise Indians into whites, often served similar consciousness-raising functions.

The Indian had refused to be preserved under museum glass, smoking peace pipes, riding horses and signing treaties that would be ignored by greedy white men. Instead, the Indian smoked cigarettes, drove pickup trucks and, in some cases, opened casinos visited by greedy white men.

Even as the pendulum swung from viewing Indians as wholly despicable to wholly admirable, the Indian story was still based on that small window of time at the end of the 19th century -- and inevitably told not by Indians, but by whites.

"You think about those John Wayne films when the Indian was the savage and you hear the bugle and you imagine that old line from Mighty Mouse -- 'Here I come to save the day,'" Iverson says. "Then you think about that Kevin I-will-be-in-every-scene Costner film, Dances With Wolves, and instead of the bugle, you have a flute. Every time you heard the flute, you knew something terrible was going to happen to the Indians."

Strickland, of Osage and Cherokee heritage, says Indian films almost always involve war. "They become a mirror for examining what was happening in the nation," he says. "Before World War II, you have films like Drums Along the Mohawk in which settlers are fighting vicious Indians who are stand-ins for Nazis and other fascists. Then in the '60s and '70s, you have the Vietnam war played out on the American Plains. Instead of the massacre at My Lai, you have Sand Creek."

Stereotype

Reinhardt says that any stereotype does damage. "Even as they change over time and become ostensibly positive, they were still limiting in their own way by pigeonholing Indians ... ," Reinhardt says.

"So today's Indian people still have to battle these stereotypes. What some of them have voiced to me on numerous occasions is that they continue to fight to say, 'We are still here.'"

Gerald McMaster, a Plains Cree who is head of exhibitions at the new museum, says that is one of the main messages the museum hopes to convey.

"It is this story, principally, that we really want to tell the visitor, that indeed native peoples not only exist today, but that we are diverse, we live across the hemisphere, in almost every country in the Western hemisphere," he says.

"We have engaged the communities at every turn, because we realize that they are the authorities of their cultural information, their histories, their cosmologies and their philosophies," McMaster says.

Copyright © 2004, The Baltimore Sun

Rob's comment

This page is devoted mainly to how Native stereotyping happened. For more on why it happened, see The Political Uses of Stereotyping.

More on the history of stereotypes

Mythologizing the American West

Plains Indians = frontier fantasy

1911: When Indians were children

The first Native stereotypes (ever)

The problem with Curtis's photographs

Related links

Tipis, feather bonnets, and other Native American stereotypes

The harm of Native stereotyping: facts and evidence

Stereotype of the Month contest

The essential facts about Indians today

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.