The good

A collection of testimonials to the man who may represent America best:

In the Harris Poll of the most popular movie stars, conducted since 1993, John Wayne has ranked as follows:

This is an impressive testament to Wayne's continuing popularity, especially since he died in 1979.

John Wayne was named the No. 1 favorite movie star of all time in a Gallup Poll this past March. His movies continue to post high ratings when shown on television. Several of his classic films were recently released on DVD. He's even appearing in a new Coors beer commercial. These are pretty heady accomplishments for Wayne, considering he died 22 years ago at age 72.

Susan King, LA Times, 7/8/01

The Quigley poll of the biggest box-office stars suggests that the moviegoing public is always more loyal to men than to women. Of all the stars who have made the top 10, John Wayne remained on the list longest. He first made the list in 1949 and lasted through 1974, missing it only once, in 1958. In four of those years he was No. 1.

Over the last half of the 20th Century, America has had a true Hero, in every sense of the word. He was a true Christian, and he taught values to the youth as well as to the adults. He taught wrong from right, good from evil, and set the example of what God intended for a man to be. He was the toughest American ever to exist, and to this day, no man has, or will ever fill his shoes.

From a fan website

At the time of John Wayne's death, President Jimmy Carter said, "He was bigger than life. In an age of few heroes, he was the genuine article. But he was more than a hero. He was a symbol of so many of the qualities that made America great. The ruggedness, the tough independence, the sense of personal courage—on and off screen—reflected the best of our national character."

John Wayne was the portrait of America. He was the Ambassador that told the rest of the world what America stood for. When America went to war, the rest of the world knew what they had to deal with. They had to deal with the spirit of America which IS JOHN WAYNE. By becoming so believable in the roles he created, even today, 20 years after his passing, young children and men alike still try to emulate the standards that he set.

Love him or hate him, you can not deny that he accomplished what no other actor has duplicated. The purest representation of American ideals, standards, and goals.

From a fan website

You know, I've always liked the cowboys,

and the war heroes,

Men like Roy Rogers, Audie Murphy,

and who could forget John Wayne?

John Wayne, as American as baseball,

a living legend in his time,

He carried a torch for America brighter than

the lights of Dallas,

And stood as imposing as the Statue of Liberty.

John Wayne—a symbol of America.

Beverly Hearn Cook, Tribute to John Wayne

There is no one who more exemplifies the devotion to our country, its goodness, its industry and its strengths, than John Wayne.

President Ronald Reagan

The bad

An excerpt from John Wayne Must Die by Robert Flynn (San Antonio, TX):

...John Wayne didn't die.

John Wayne became the hero of America, replacing such impostors as Lindbergh, Clarence Darrow, Albert Einstein, Audie Murphy, William Faulkner. He became the icon of the west, replacing such impostors as Sam Houston, Chief Joseph, Teddy Roosevelt, Bill Haywood, Will Rogers.

John Wayne was spit and image of the American hero. He was tougher than a longhorn steak until real bullets flew. He was meaner than a side-winder if someone sat on his hat, beat his woman or was discourteous to a horse. But only on film. He stood tall, walked proud, and pretended the deeds that sent Nazis to the hanging tree and his addled sidekick, freeze a vet for HUD Reagan, to the White House.

John Wayne was charmingly inarticulate. He had only twelve words in his vocabulary other than Winchester, six-shooter, kill, shoot, maim, horse, dog and pilgrim. Six of the remaining words were conjugations of "Wal." Don Quixote might have been addled but he wasn't incoherent. In the theater, even heroes have to speak. In novels, even stupid men have to be able to think. Starve a kid and make a Buck Reagan wasn't inarticulate, he was just dumb. It took movies to give us "yep" heroes. Movies started out silent anyway. They remained dumb, they just added sound.

John Wayne didn't need nobody. He didn't ask favors. He didn't take handouts. He pulled himself up by his own six-shooters.

John Wayne had no self-doubts. His opinion was right and you were welcome to your own as long as it agreed with his. He was on the right road, headed in the right direction and if you didn't get out of his way he'd kill you. Or maybe just maim you if you had made an honest mistake. Although he sometimes let women and children live. Unlike his inept sidekick, don't give a Hoot Reagan.

And John Wayne didn't die.

John Wayne never broke a sweat for daily bread, toiled at a repetitive and humbling job for minimum wage, or was gainfully employed, except at killing people. His only skill was violence, but it was the skill most honored and most envied by his countrymen.

And John Wayne didn't die.

John Wayne loved freedom. The freedom to go wherever he wanted to go, to whatever he wanted to do, and kill anyone who wanted the same. He was the quickest to violence. Always. Leaving slower men dead in the street.

Wayne had values. Good horses. Good dogs. Good whiskey. Good violence. He hated bad violence and killed bad-violent men. He was more violent than anyone, but for a good cause. He only killed those he though needed killing. He had a code that permitted no extenuating circumstances and no exceptions. Except himself. And his fatuous sidekick, Save the Rich Reagan.

John Wayne was innocent. No matter how many people he killed, or how much pleasure or satisfaction he got out of it, he maintained a boyish innocence about the whole bloody business. Well, sure, some good men died too. And some women caught in the crossfire. And some babies. Some babies always die. But when you look up there and see old glory waving in the breeze, high up there, on top of the Savings and Loan Building, it makes you wish the taxpayers weren't so gol darned cheap and had given you a few more bullets to waste.

John Wayne didn't lose. Right means might so John Wayne couldn't lose. John Wayne wasn't at Wake Island or Corregidor. Because John Wayne didn't lose. He left Vietnam early. I didn't see the Alamo. I don't know how he got out of that.

John Wayne didn't lose and John Wayne didn't die. They had to bring in an Australian to bravely and defiantly kill Indians in a gallant last stand. Custer died. John Wayne didn't die. I've been in the Alamo. And I know that John Wayne is in there somewhere. And he's alive.

Okay. Some red-eyed insomniac with sixteen VCRs is going to say John Wayne died in Vietnam. I've been out of boot camp a long time. I'm a college professor now and no one is smarter than a college professor. Except John's lambent sidekick, cut and run in Lebanon, Duck Reagan, who couldn't remember who was president while he was in the White House, whether or not he sold arms to Iranian terrorists, or what use was made of trees. "Well, I know when I was president they caused pollution. It was called trickle-down smog."

John Wayne didn't die. His spirit transcended him, passed into the souls of Americans everywhere. The story that St. John bodily ascended into heaven while his back-shooting sidekick, praise a vet and make a Buck Reagan went to hell is probably not true. That's an exaggeration combined with an understatement. No, John Wayne passed into the spirit of Americans who died in Beirut, Grenada, Nicaragua, Libya, Panama, Iran, Iraq. John Wayne didn't die.

A few years ago I interviewed some Kickapoos who clung to their tribal ways, resisting if not denying the twentieth century. How do you learn what it means to be a Kickapoo? I asked them. How do you learn what it means to be a Kickapoo man, or woman? How do you know what is expected of you as one of these people?

From the stories, they said.

What stories?

The stories the grandmothers and grandfathers told us, they said.

I asked them to tell me the stories but they wouldn't. If I knew the stories, I would be Kickapoo, too.

What are the stories that tell us how to be human? That tell us what is good, what is true, what is beautiful?

The Kickapoos never heard of Shelley, but I think they would have agreed that you become what you behold. What are the stories that tell Americans how to be men when women and children don't measure up to your standards for them? When other men don't get out of the way of your ambition? When teachers, parents or peers try to fence in your ego? When inferiors like Libyans, Panamanians, Nicaraguans pretend they have the same rights as you have?

St. John had the answer. St. John taught us, big and powerful is good. Small and weak is bad and must be killed. Or at least exploited.

St. John told us that a man should take everything he can get, and the quickest way to get it is with a gun.

St. John taught us that the first to use violence is the winner, the fastest to the trigger is the hero.

John Wayne didn't die. John Wayne lives in the souls of those who believe bullets speak louder than words, who believe a gun, a quick draw and a steady aim are the only Bill of Rights we'll ever need.

John Wayne must die.

The ugly

On the reservation, he and others would play cowboys and Indians because they were American, too, he says. Watching Westerns, he would root for John Wayne, he adds.

"I distinctly remember doing that because I didn't recognize those Indians; I wasn't those Indians; I wasn't running around in a loincloth. I wasn't vicious. I wasn't some sociopath with war paint." Alexie says.

Interview with Sherman Alexie

CBSNews.com, 3/20/01

I don't feel we did wrong in taking this great country away from them. There were great numbers of people who needed new land, and the Indians were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.

John Wayne

Comment: Those darn Indians. They selfishly tried to keep themselves alive while the US selflessly tried to exterminate them. The nerve of some people!

That Wayne voiced the excuse of the typical cowboy and American is telling. We couldn't help it if we broke our treaties with the Indians, stole their land from them, and killed them if they got in the way. We're goodness personified, so we can't do wrong by definition. No wonder Wayne is revered by so many Americans.

Who's the real hero?

As Beverly Hearn Cook's poem and Robert Flynn's essay make clear, Americans consider John Wayne their greatest hero. Although he sat on his duff during World War II, Cook equates him with Audie Murphy, the most decorated real soldier of WW II. A Milwaukee Journal editorial (6/6/94) made the link clear when it ironically noted that "while war must sometimes be waged, it is almost never the bloodless, black-and-white, 90 minute spectacle that John Wayne and Audie Murphy portrayed."

Let's examine the thesis that John Wayne was a real-life Audie Murphy—er, that Audie Murphy was a real-life John Wayne. Murphy's experience as a hero is most instructive about the American character...and the John Wayne myth.

From an article titled "Secrets at the Bottom of the Drawer" by David Weddle. In the LA Times, 7/22/01:

The phenomenon began with the 50th anniversary of the end of WW II, and has continued with the nostalgia wave. More and more soldiers—men who never exhibited overt symptoms before, who used to scorn Vietnam vets for claiming to have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—have been walking into VA counseling centers and asking for help. More than 32,000 WWII veterans have sought psychological treatment at vet centers since 1996. Most have led normal, productive lives, at least on the surface. They married, raised children and enjoyed careers as accountants, architects, lawyers, electricians, small business owners and so on.

But now, in their 70s and 80s, they have been debilitated by memories of events on distant battlefields a half-century ago. Many have nightmares, others find themselves crying uncontrollably when the subject of the war comes up, and some have three-dimensional flashbacks that force them to relive traumatic combat experiences.

"Many of these veterans have possibly been suffering PTSD since their return home in the 1940s and '50s," says Dr. Kenneth Reinhard, a clinical psychologist at a VA hospital in Montrose, N.Y. Reinhard, son of an infantryman, Edward Reinhard, who fought on Guadalcanal, has treated hundreds of WWII soldiers for PTSD in the last five years. He currently runs four weekly group therapy sessions for them. "These are tough children of the Great Depression, who went to war, won it and came home to build fresh lives," he says. They have known terrible privation and horrific violence, but learned they couldn't afford to wallow in their emotions. Tears wouldn't put food on the table or knock out the machine gun killing their friends. So they swallowed their feelings, got the job done and moved on.

But now all of the hurdles have been cleared. They've retired and are no longer able to keep their minds occupied by working 15 hours a day. There's time to remember, and all those feelings they swallowed have started to bubble back up again, primed by incessant WWII tributes and the deaths of wives, siblings and friends that remind them of other loved ones lost years ago.

Reinhard believes these men are just the tip of the iceberg. There are no reliable statistics to pinpoint how many of these old soldiers might have PTSD, but two other psychologists who have studied the VA's medical records agree with Reinhard. Elizabeth Clipp of the VA and Glen Elder Jr. of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill write: "There is evidence that PTSD in World War II veterans is currently underdiagnosed because of an unwillingness on the part of veterans to associate current symptoms with war experiences. Symptomatology is sometimes misdiagnosed as anxiety, alcoholism, depression or schizophrenia."

Many veterans I interviewed admit to having symptoms similar to Reinhard's patients, either now or earlier in their lives. Most common are nightmares from which they wake up screaming and sweating. Some experience free-floating anxiety, depression or phobias such as claustrophobia or an aversion to crowds.

Thaine High of Oceanside can't stand the smell of meat on a barbecue. High was a graves registration officer in Europe. He and his eight-man squad picked up more than 1,700 corpses from the front lines in France, Belgium, Germany and Czechoslovakia. "The worst thing were the tank battles," he explains. "If a tank was hit and burned, you had to wait until the tank cooled down, sometimes two or three days. We'd get the five names of the men who were in it from the tank commander. After the tank cooled down, we'd go in and open the hatches and try to get some kind of remains from the bodies. If we were lucky, we'd find an arm, a leg, or a foot, sometimes a skull." His voice quivers. "To this day I can hardly stand to have a barbecue because it reminds me of the burnt flesh."

The Angry American

It's not surprising that WWII veterans tried to conceal their psychological wounds, if one pauses to consider the social climate they returned to. The government and the media told them to shrug off the past and embrace the good life they'd fought to preserve. In 1946, movie director John Huston, who was still in the Signal Corps, made a harrowing documentary about the war's "neuropsychiatric casualties," which made up about 20% of the casualties in the war. It included hair-raising footage of soldiers with severe psychosomatic symptoms such as stutters, amnesia and paralysis. The Army decided the movie was off-message and locked it in a film vault for more than 40 years.

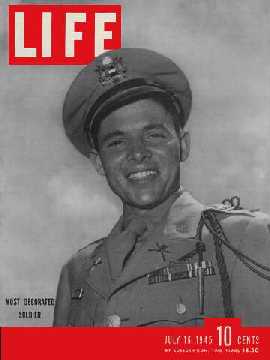

Instead of Huston's shattering depiction of "casualties of the spirit," the government and media preferred to hold up America's most decorated soldier, Audie Murphy, as the role model for veterans. Newspapers ran countless stories on this freckle-faced Texas kid who had single-handedly killed 240 German soldiers. Gary Cooper, who had played Sgt. York in the movies, befriended Murphy. Life magazine put him on the cover and ran photos of the clean-cut small-town kid getting a haircut in his local barbershop, and showing his sister Nadine a German sniper rifle—a trophy from one of his kills. Journalists gushed that Murphy was "the nicest boy you ever saw" and "a swell kid, absolutely modest and sincere and genuine and unaltered by terrible experiences."

"That last phrase—unaltered by terrible experiences—was the key," Don Graham wrote in his biography of Murphy, "No Name on the Bullet." "That's what Audie Murphy was intended to represent in his incarnations as the nation's darling young soldier—hero. . . . It was terribly important that these returning veterans be perceived as still our boys, untouched, unchanged, the nightmare behind them. They could resume their lives just as the American people could resume theirs."

But Murphy had been altered. At first only a few friends noticed, but as the years passed, the public began to recognize that something was terribly wrong. He constantly complained of being tired, yet couldn't sleep. When he did, nightmares came. One time he pounded a wall in his sleep until his fists were cut and bleeding. Other times he bolted upright from his bed, pulled the pistol from beneath the pillow and shot clocks, mirrors and light switches. Then there were the public brawls in which he beat opponents to a bloody pulp with a riding crop or pulled guns on them.

.

.

.

The Great Turkey Shoot

In January of 1949, Audie Murphy married a Hollywood starlet, Wanda Hendrix. Audie and Wanda were hailed as America's golden couple. But Wanda realized something was terribly wrong at the altar. "It was the moment I lifted my veil for him to kiss me that I noticed the change," she later recalled in Graham's book. "His eyes were those of a stranger." After the ceremony, Audie told her, "If there's a God in heaven, I hope he forgives me for what I've done to you tonight."

In the following months, Wanda discovered what he meant. Murphy turned cold and critical. He ridiculed her in front of friends, and finally, there were the guns. "The big thing in his life was his guns," she said. "He cleaned them every day and caressed them for hours." There were the times he bolted from his sleep and shot something off the wall, but far worse were the times he turned a gun on her. "He held me at gunpoint for no reason at all. Then he would turn around and put the gun in his own mouth. I finally told him one night to go ahead and shoot. He put the gun away and turned all white."

What would motivate America's most decorated soldier, by then not only a national hero but also a successful movie star, to stick a gun in his mouth? Perhaps the same dark forces that propelled so many WWII veterans toward self-destruction.

.

.

.

Why were so many of these young men, who had won the war and returned as heroes, so determined to throw their lives away? One answer is survivor guilt. "I was in combat for 29 months, and I wasn't wounded, and I apologize for that," says Bob Williams, who served as a machine-gunner in North Africa, Italy, France and Belgium and now lives in South Salem, N.Y. When I ask why Williams feels a need to apologize, he says, "I don't know. How come the fellow next to me was killed and I wasn't?"

Murphy seemed haunted by the same question. "The real heroes are dead," he said darkly on many occasions. For no matter how many machine-gun nests you knocked out, the re were always those other moments, the ones you never spoke of. The time a wounded and dying buddy cried out for help but you couldn't get to him because of enemy fire—or so you told yourself. The time you hesitated or almost ran—the times only you know about and secretly condemn yourself for.

But even worse than the guilt about what you didn't do, is the guilt about what you did. When Al Umbach, of Palm Coast, Fla., talks about the first German soldier he killed, his breathing becomes labored, his voice burdened. Umbach was a farm boy from Long Island, drafted into the infantry and thrown into action for the first time in the Battle of the Bulge. "The Germans were retreating, and there was a raised railroad track. They were going over this track, and the one guy, I hit one guy and—what bothered me—he never, he tried to get up and I took him out again and I— you know, that, that's nasty. I kept thinking, 'Don't stand up, please don't stand up.' I felt anger that the guy didn't have sense enough to stay down—that's about all that I can—I don't really—you're trained, you're trained, it seems kind of cold and everything, but that's what we were trained for. You knew, I mean, the one thing that an infantryman knows and is drilled into him is that if somebody points a gun at you, kill him first before he kills you."

Yet Umbach can't help thinking about that young German these many years later. "I wonder if he had a family, if he had a girlfriend. I had a girlfriend before I went overseas and I married her—we've been married for 50 some years. You not only think about that one person that I killed, but all the young men on both sides that lost so much of the future."

That "war is hell" is no secret...except, that is, to America's cultural myth-makers. Whether it's the feel-good "historians" who write books and raise monuments to America's heroism...the Hollywood producers, video-game makers, and comic-book publishers who glorify the biggest and baddest brutes...or the happy-faced Pollyannas who write paeans to John Wayne's memory...we're engaged in a collective case of denial. It's time to stop denying and start dealing with reality.

John Wayne wasn't a hero, he was a freakin' actor. If he had been a hero, he would've been a traumatized victim just like so many war veterans. The "heroes" we worship—your Rambo, Punisher, and rap-star types—would be the same way if they were real. They wouldn't be standing tall, protecting us from Commies, crooks, or gangstas. They'd be a quivering mess with guns in their mouths.

Americans don't want to deal with the reality of death and violence. They don't want to deal with the reality of racism and sterotyping. They want short-term, pragmatic solutions that requirement no thought, planning, or sacrifice. That's part and parcel of what makes them American.

They're myopic, in other words. And that's why they need a multicultural perspective. Why they need comics like PEACE PARTY and websites like this one to shake them up.

I hope this study of John Wayne helps clarify what it means to be an American. If it still isn't clear, the following links may help.

More on John Wayne

Indians in Red River

Apaches in Hondo

George W. Bush = John Wayne

Rio Grande isn't grand

Noble Americans in Fort Apache

John Wayne's mainstream Westerns

John Wayne respected Indians

Review of She Wore a Yellow Ribbon

A century of John Wayne

Related links

A shining city on a hill: what Americans believe

Violence in America

America's cultural mindset

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.