The Political Uses of Stereotyping

By Rob Schmidt

Chief, brave, squaw. Warrior, mystic, nature lover. Savage, thief, drunk. When most people think of Native Americans, these are the images that come to mind. They're stereotypes, to be sure, but they have a staying power as strong as the truth.

Ever since Columbus bumbled into America and mislabeled the inhabitants "Indians," people have used stereotypes to distort the natives' reality. These fictions aren't just the ignorant or misguided choices of individuals. They're part of a systematic attempt to strip Indians of their identities—and their resources.

The Western urge to dominate others was born in the beginning. "The colonizing religions of the Old World—Judaism, Christianity and Islam—all trace back to Abraham, and through him to Noah and to Adam," writes Steven Paul McSloy.1 In fact, the biblical God's first command was to conquer:

And God blessed them: and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the heavens, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth. (Genesis 1:28)

This assertive attitude continued through the centuries. "Rome's unholy synthesis of Christian ethics and Jewish (God-given) and Roman (Imperial) law provided Rome the absolutist, self-righteous authority to conquer the western world," writes Gerry Lower.2 St. Augustine defined non-Christians as sick or evil. Popes declared themselves infallible and launched Crusades and the Inquisition.

As the Age of Exploration dawned, one papal bull urged "intrepid champions of the Christian faith ... to invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans whatsoever" (Romanus Pontifex, January 8, 1455). Once Europeans became aware of the Americas, another papal bull claimed the noblest work was "that barbarous nations be overthrown and brought to the faith itself" (Inter Caetera, May 3, 1493).

This lust to vanquish and overthrow begat perhaps the biggest myth of the last 500 years: that Christopher Columbus "discovered" America. That the continent was virgin territory, free for the taking and ready to be occupied.

This so-called Doctrine of Discovery let Europeans justify their thievery. It was responsible for centuries of colonization and exploitation. American courts ultimately used it to turn sovereign native nations into wards of the state.

Many people don't know this history, but they do know about Columbus and his "heroism." Glorifying him means glorifying the resulting depredations. As James Loewen writes:

The way American history textbooks treat Columbus reinforces the tendency not to think about the process of domination. ... When textbooks celebrate this process, they imply that taking the land and dominating the Indians was inevitable if not natural.3

Because the Indians were inconveniently in the way, Columbus and those who followed began the task of diminishing them. "Over and over again the inhabitants of the Americas were characterized in firsthand accounts as (1) naked, (2) childlike, (3) willing to share anything they possessed, (4) unaware of religion, and (5) unconcerned with laws or personal property," writes Raymond William Stedman.4 If that didn't work, Europeans tried the opposite tack: demonizing the natives as savages, killers, and cannibals. In Spain, philosophers debated whether Indians had souls, with Juan Gines de Sepulvèda calling them "homunculi" and as different from Europeans as apes were from men.

Thus began the dichotomy of the "good Indian" and "bad Indian." Indians were good when they helped the foreigners enrich themselves: leading explorers to El Dorado or the Northwest Passage, guiding fur trappers or friars, or simply keeping colonists alive. They were bad when they resisted encroachment, fought back, asserted their territorial rights. But both figures demonstrated that the Euro-American cause was just and the outcome inevitable.

On the good side were real-life collaborators such as Pocahontas, Squanto, and Sacagawea. Joining them were the fictional embodiments of Tonto, the Lone Ranger's "faithful Indian companion." These included Daniel Defoe's man Friday, a Carib Indian, and James Fenimore Cooper's Chingachgook, the "last of the Mohicans." As The Straight Dope observes:

After the Indian wars, Sacagawea and other "good Indians" ironically became symbols of the rightness of m�anifest destiny and white displacement of the Indians. Here was an enlightened Indian maiden, the thinking seems to have been, who recognized the superiority of the white race and the inevitability of subduing the west. That this unusually perceptive Indian helped achieve that goal just goes to show that the conquest of the west was best for the Indians too, even if they didn't know it yet.5

The "good Indian" was similar to the "good Negro"—the Mammy or Uncle Tom—seen in old minstrel shows, books, and movies. As Reena Mistry writes:

The underlying message of such images is clear: the slave is someone who is willing to serve their master; their devotion allows a white audience to displace any guilt about their history of colonialism and slavery.6

Good Indians made perhaps their biggest mark in Plymouth, Massachusetts. There the Pilgrims took the "paradise" Columbus found and built a shining "city on a hill." Despite the Spanish settlements in the Southwest and Florida and Jamestown in Virginia, Americans thought and think of this as the country's birthplace.

Our national origin myth

The first Thanksgiving is arguably the apotheosis of the myth-making begun in 1492. Celebrated in school plays and parades, it's our national origin myth, says Loewen. "The archetypes associated with Thanksgiving—God on our side, civilization wrested from wilderness, order from disorder, through hard work and good Puritan character traits—continue to radiate from our history textbooks," he notes.7 Moreover,

The Thanksgiving legend makes Americans ethnocentric. After all, if our culture has God on its side, why should we consider other cultures seriously? This ethnocentrism intensified in the middle of the last century. In Race and Manifest Destiny, Reginald Horsman has shown how the idea of "God on our side" was used to legitimate the open expression of Anglo-Saxon superiority vis-à-vis Mexicans, Native Americans, people of the Pacific, Jews, and even Catholics.8

Conservatives have used Thanksgiving to construct a vision of America founded by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants—in other words, people just like them. This vision is never about how the colonists would have failed and died without the intervention of strangers (Indians) with an alien culture and creator. It's about how God favored his children with help, thus proving Euro-Americans were the "chosen people."

To be sure, there was a constant tug-of-war between the "good" and "bad" narratives. After the Pequot War and King Philip's War, negative characterizations of Indians became more common. As Gary B. Nash explains, the invaders had good reason to portray the natives this way:

To typecast the Indian as a brutish savage was to solve a moral dilemma. If the Indian was truly cordial, generous, and eager to trade, what justification could there be for taking his land? But if he was a savage, without religion or culture, perhaps the colonists' actions were defensible.9

Euro-Americans used similar techniques to assuage their guilt over slavery. As the transatlantic slave trade grew, Nash reports, "We find words like 'brutish,' 'savage,' and 'beastly' creeping into English accounts of Africans. In almost all these respects the image of the African coincided with the image of the Indian after the first period of contact."10

So Africans and Indians were stereotyped in similar ways for similar reasons. As Mistry puts it, the parallels are clear:

The primitivism of black people demonstrates their suitability to their servile positions; the fear of their unpredictability provides justification for maintaining control over them, while the image of the civilised white man 'confronting his Destiny' makes the exercise of this control not only acceptable, but also respectable.11

After a century or so of encroachment, the colonists had expelled the tribes from the Eastern seaboard. These proto-Americans were then able to look at their former neighbors with grudging respect. Having eliminated the immediate danger, they began incorporating Indians into their stories as reference points.

"In the British political cartoons of the mid-eighteenth century," writes Philip Deloria, "the Indian became a familiar symbol of the American colonies themselves. Between 1765 and 1783, the colonies appeared as an Indian in no fewer than sixty-five political prints—almost four times as frequently as the other main symbols of America, the snake and the child."12

Indians represented the "spirit of the continent," he adds. They embodied a range of values: wild, untamed, rebellious, free. When the colonists wanted to protest onerous British measures, they often dressed up as riotous Indians. The Boston Tea Party is merely the most famous example.

Playing Indian was a way for the interlopers to transform themselves into authentic Americans. As Deloria observes, "Conflating Indians and land, the rioters suggested that these qualities lay embedded in the American soil itself and that, as the environment reshaped settlers' personalities, freedom and liberty had made their way into the psychic makeup of white Europeans."13

Back in Europe, philosophers far from the reality imagined Indians as "noble savages." The natives were acting naturally, as God intended, free from manmade restrictions, they theorized. This existence was a bracing revelation for people born to serve church and crown. "Seeing examples of indigenous democracies of North America, eventually led European intellectuals to envision the possibility of a different kind of political order based on 'liberty,' without monarchy," writes Steve Newcomb.14

Throughout the colonial period, Indians vacillated between being allies and enemies. Jefferson deemed them "merciless savages" in the Declaration of Independence, and Washington, nicknamed "Town Destroyer" by the Senecas, ordered their villages razed. But tribes fought as equals on both sides of the Revolution, and the Americans, desperate for military aid, considered giving the Delawares their own state.

The natives traded furs and other goods, signed treaties and sold land, and forged alliances during conflicts. "These transactions had symbolic as well as legal meaning for they served as reminders that the Indian, though often despised and exploited, was not without power," writes Nash.15 Because Indians still had their uses, few people talked of exterminating them—yet.

After the war, the newly minted Americans began migrating west in search of their so-called "manifest destiny." To facilitate this, they began romanticizing the natives. Paintings showed and stories told how Indians lived in some timeless Arcadian past. Plays portrayed Pocahontas, Metamora, Minnehaha, and other semi-mythic Indians. Longfellow's epic Song of Hiawatha closed with the Iroquois leader literally sailing into the sunset.

Deloria describes the thinking behind these sentimental lamentations:

In conjunction with Indian removal, popular American imagery began to play on earlier symbolic linkages between Indians and the past, and these images eventually produced the full-blown ideology of the vanishing Indian, which proclaimed it foreordained that less advanced societies should disappear in the presence of those more advanced. Propagandists shifted the cause-and-effect of Indian disappearance from Jacksonian policy to Indians themselves, who were simply living out their destiny.16

Even the terminology supported the march of progress (at the Indians' expense). Americans were "pioneers" ... pushing the "frontier" ... taming the "wilderness" ... bringing "civilization" ... although Indians had already done these things. Indeed, when Loewen asked college students when America was first "settled," the consensus answer wasn't some prehistoric date such as 12,000 BC but 1620.17

Rhetoric turns virulent

As Americans intruded deeper into the remaining territories and the Indians retaliated, the rhetoric became more virulent. Elegies such as Horace Greeley's Lo! the Poor Indian! gave way to arguments for the Indian's elimination. "He is ignoble—base and treacherous, and hateful in every way," wrote Mark Twain.18 "The rude, fierce settler who drives the savage from the land lays all civilized mankind under a debt to him," wrote Teddy Roosevelt.19 "Having wronged them for centuries we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth," wrote L. Frank Baum.20

Like the Japanese Americans interned in concentration camps during World War II, Indians were victims of a "racial smear campaign," notes H. Mathew Barkhausen III. "How on earth could an entire population have been motivated to perceive the Japanese Americans in such an extraordinarily negative light? The answer of course is in the despicable propaganda campaign of political cartoons, films, and other forms of racist media."21

The Indian Wars ended with the natives' capitulation, but the cultural wars continued. Americans had to find a way to deal with people who were vanquished but not vanished. Using language not unlike the popes' four centuries earlier, they insisted the Indians submit and conform:

The legal status of the uncivilized Indians should be that of wards of the government; the duty of the latter being to protect them, to educate them in industry, the arts of civilization, and the principles of Christianity. ... The religion of our blessed Savior is believed to be the most effective agent for the civilization of any people.22

To hasten the process, officials banned the Indians' religious ceremonies, ensconced their children in boarding schools, and doled out their land to individuals (while selling the "surplus" to whites). They castigated uncooperative Indians as drunk, lazy, or good for nothing. It was the old duality at play again. Good Indians leapt at the opportunity to become "civilized"; bad Indians didn't.

Trapped between two cultures, Indians had a "halfway-house status," writes Stedman. The popular literature about them revealed "psychological cripples and disillusioned alcoholics ... as embittered products of defeat."23 This view was encoded in James Fraser's much-copied 1915 sculpture "The End of the Trail."

Depicting Indians as losers has long been part of the dominant strategy, as Scott Lyons explains:

Representing Indians in the tragic mode is nothing new—think "Last of the Mohicans" or "Dances with Wolves"—because the "Vanishing Indian" was never meant to have a future in the first place. This is how culture has always supported colonialism.

To the extent that Natives are perceived as perched on the brink of extinction, settlers can feel secure in their knowledge that this really was an "empty continent," thus justifying their presence on it. Purging one's emotions over the awful effects of colonization is part of the process of justification—hence, the persistent proliferation of tragic narratives.24

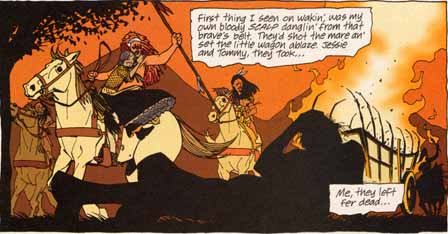

While the actual Indian declined, the mythical Indian rose. Wild West shows, dime novels, and Remington paintings—soon followed by Western movies—coalesced around Plains Indian images: the chief, the brave, the teepee. These stereotypes helped to reduce Americans' remorse but also to bolster their identity. That was necessary because a new threat loomed.

After the Great Famine of 1845-1849, a wave of Irish immigrants hit the US. The newcomers were treated much like the Indians and Africans before them. "Negative stereotypes, supported by much of the Anglo-American population, characterized the Irish as 'pugnacious, drunken, semi-savages,'" reports one website.25 "Newspapers described them as 'Irish niggers' and 'a mongrel mass of ignorance,'" reports another.26

America faced increasing industrialization and urbanization. Then, between 1900 and 1915, a flood of immigrants—Italian Catholics, Orthodox Slavs, and Jews—entered the country. "The popular press often linked Indian people with the 'inferior' east and south European immigrants peopling the urban slums and low-wage factories," writes Deloria.27 Just as the US was resolving its "Indian problem," it was turning immigrants into the new Indians.

A book review of Alan Trachtenberg's Shades of Hiawatha suggests how Americans used one dilemma to solve another:

Trachtenberg writes how the image of the fading, noble Indian was part of a long process of refashioning history. This featured a "remaking of alien natives into model Americans" who then became "models for those immigrant aliens." At the turn of the century in ascendant America, these new arrivals with their strange languages and cultures seemed far more menacing than the long-conquered native inhabitants of the continent.

And:

"Indians had been slaughtered; for the sake of the new race of Americans, they must be resurrected and commemorated, their 'pure' image preserved in gold," Trachtenberg writes. ... "Freezing the Indian image as 'pure' so that it could be incorporated as an ingredient in American whiteness was a cure to both blackness and the 'inferior' strains from Eastern and Southern Europe," he writes.28

As real Indians sank into obscurity, the stereotypical chief began appearing everywhere. Planes, trains, and automobiles were named after him (as were many other products). Colleges and high schools chose him as their mascot. The Boy Scouts of America modeled themselves on him. By linking themselves to Indians, 20th-century Americans celebrated their victories and touted their virtues.

Some picture-Indians looked noble and dignified, but others were crude and buffoonish. Chief Wahoo and other big-nosed, wild-eyed caricatures became prominent in cartoons and advertisements. These images proclaimed the Indians' inferiority and implied they deserved what they got. Exaggerated images of blacks, Jews, and other minorities sent a similar message.

Questions arise

With lynchings and labor riots, a great depression, and a world at war, some observers began to question the nation's values. Ernest Thompson Seton, who wrote the first Scouting manual, was one. "Our system has broken down," he charged. "Our civilization is a failure."29 To him the Indian was an alternative, an ideal for others to emulate.

In the 1960s, doubts about America's direction reached a pinnacle. People again turned to Indians for inspiration, this time in their imagined role as mystics and ecologists. The implicit wish was to reconnect with authentic, earth-based cultures. Hippies became faux Indians by donning beads and buckskins, living in rural communes, and adopting New-Age beliefs.

Since then, other stereotypes have come to the fore. They're primarily employed by conservative-leaning status seekers. Like the Pilgrims and pioneers, these people are striving for the American Dream and don't want anything to impede them.

The new and improved stereotypes include:

Indians as casino owners. Americans now see Indians the way they used to see Jews: as rich, greedy, and corrupt. As an editorial explains:

Like European Jews, Native Americans have developed particular financial industries because they have been denied control over land, and left with few other economic options. And like the myth of the "rich Jew," the myth of the "rich Indian" implies that all tribal members are swimming in money. The truth is that most tribes are heavily in debt, cutting budgets, and still being shaken down by state governments.30

This is scapegoating, says Zoltan Grossman, and it serves several purposes. Among them:

To win over "Middle Americans" by diverting animosity toward the poor, but also by emphasizing the economic threat from above to detract attention from ruling institutions.

To portray white Christian citizens as underdogs, which can mask the historic theft of land by claiming a new "theft" of their wealth.31

Indians as socialists. James Watt, Reagan's disgraced Secretary of the Interior in the 1980s, called reservations "the last bastion of socialism in North America." Libertarians make similar claims every Columbus Day when they write how lucky Indians were to join Western civilization. In New York Times and Wall Street Journal editorials, they revise history to say Congress has "granted" sovereignty or "invented" tribes. Echoing Watt, they declare the reservation system should end.

It's all an effort to denigrate "big" government and its social programs. These naysayers advocate a "survival of the fittest" society where the rich and mighty rule and the will of the people is thwarted. With their communal and spiritual cultures, Indians stand as an obstacle and a rebuke to these goals.

Indians as mascots. Commercial products, newspaper cartoons, and sports logos still feature the ubiquitous Indian chief or warrior. Supporters of these images bawl like babies when anyone tries to remove them. After the NCAA's 2005 ban on mascots in postseason tournaments, CNN's Lou Dobbs labeled the decision an "Orwellian exercise," "academic political correctness," and "idiotic."32 Few people care that Indians reject the "honor" supposedly bestowed on them.

Mascot backers hope to keep America's moral crimes safely in the past. If the masses think of Indians as dead and gone, they won't have to feel bad about how they've treated them. More important, they won't have to worry about upholding treaties, paying trust-fund bills, or returning property such as the Black Hills.

Indians as pretenders. Some people argue that Indians aren't who they say they are. For instance, when the Army Corps of Engineers dug up the skeleton known as Kennewick Man, scientists immediately claimed he looked Caucasian. The implication was that Indians weren't the first Americans after all and had no special right to the land.

Critics such as Shepard Krech III, author of The Ecological Indian, imply Indians weren't the environmental stewards they're alleged to be. They killed the prehistoric megafauna, hunted beaver and deer to extinction, and burned and cut down forests, speculates Krech. One can only wonder what would happen if these charges stick. Americans might turn reservations, sacred sites, and wildlife refuges into paved-over parking lots.

In 2006, riots erupted over the publication of cartoons depicting the prophet Muhammad as a terrorist. Many in the West thought the images were right on. They believe Arabs and Muslims are savage and uncivilized—the latest minority to be stereotyped like Indians.

The controversy was yet another instance of Westerners demonizing "the other" to protect their political interests. Whether it's an Arab with a bomb, an African with a spear, or an Indian with a tomahawk, the message has been consistent. "Someone is out to get us, so do as we tell you and don't ask questions." It's society's version of using the bogeyman to scare a child into submission.

"The mythology of America is based on the denial of the indigenous," Winona LaDuke has said.33 By relying on stereotypes instead of understanding Indians, we perpetuate a fictional history based on fear and doubt. Fairy tales may be fine for children, but grownups need facts. Only then can they live and act responsibly.

Notes

1. Steven Paul McSloy, "McSloy: 'Because the Bible tells me so.'" Indian Country Today, September 10, 2004.

2. Gerry Lower, "Gandhi's Seven Root Causes: An East-West Dialectic Synthesis." Posted at http://www.opednews.com/Lower_gandhi.htm.

3. James W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me (The New Press, 1995), 35.

4. Raymond William Stedman, Shadows of the Indian: Stereotypes in American Culture (University of Oklahoma Press, 1982), 20.

5. Straight Dope Science Advisory Board, "What's the real story on Sacagawea?" Posted at http://www.straightdope.com/mailbag/msacagawea.html.

6. Reena Mistry, "Can Gramsci's theory of hegemony help us to understand the representation of ethnic minorities in western television and cinema?" Posted at http://www.theory.org.uk/ctr-rol6.htm.

7. James W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me (The New Press, 1995), 85.

8. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me, 87.

9. Gary B. Nash, "Red, White, and Black: The Origins of Racism in Colonial America." Posted at http://www.toptags.com/aama/voices/commentary/racismorigin.htm.

10. Nash, "Red, White, and Black."

11. Mistry, "Can Gramsci's theory of hegemony help us to understand the representation of ethnic minorities in western television and cinema?" Posted at http://www.theory.org.uk/ctr-rol6.htm.

12. Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (Yale University, 1998), 28-29.

13. Deloria, Playing Indian, 26.

14. Steve Newcomb, "On America's Pathological Behavior Toward Native Peoples." Indian Country Today, September 10, 2004.

15. Gary B. Nash, "Red, White, and Black: The Origins of Racism in Colonial America." Posted at http://www.toptags.com/aama/voices/commentary/racismorigin.htm.

16. Deloria, Playing Indian, 64.

17. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me, 67.

18. Mark Twain, The Noble Red Man, 1870.

19. Theodore Roosevelt, The Winning of the West, Volume Three: The Founding of the Trans-Alleghany Commonwealths, 1784-1790, 1894.

20. L. Frank Baum, editorial, Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, January 3, 1891.

21. H. Mathew Barkhausen III, "'Red Face' Does Not Honor Us." Snap Magazine, February 1, 2005.

22. 1869 Board of Indian Commissioners Annual Report 10.

23. Stedman, Shadows of the Indian, 175.

24. Scott Lyons, "Leech Lake Storytelling Was Poor Journalism." Minneapolis Star Tribune, June 5, 2004.

25. Dan O., Katherine F., Julia M., "Irish Immigration." Posted at http://nhs.needham.k12.ma.us/cur/kane98/kane_p3_immig/Irish/irish.html.

26. "In the City of Brotherly Love." Posted at http://www.tolerance.org/teach/printar.jsp?p=0&ar=526&pi=apg.

27. Deloria, Playing Indian, 104.

28. "What It Means to Be an Indian in America." Hartford Courant, January 9, 2005.

29. Ernest Thompson Seton and Julia M. Seton, The Gospel of the Redman, 1936.

30. "Indian-Bashing: a New Pastime in 'Tolerant' Dane County?" Wisconsin State Journal, 12/29/03.

31. Zoltan Grossman, "Rich Tribes, Rich Jews: Comparing the New Anti-Indianism to Historic Anti-Semitism." PowerPoint presentation.

32. Transcript of CNN broadcast, August 9, 2005.

33. Winona Laduke, "Social Justice, Racism and the Environmental Movement." University of Colorado at Boulder, September 28, 1993.

This article is available for reprint but may not be reprinted without permission. Contact the author for details. All rights reserved.

More information about Native stereotyping

Tipis, feather bonnets, and other Native American stereotypes

A brief history of Native stereotyping

Stereotype of the Month contest

Related links

America's cultural mindset

Native vs. non-Native Americans: a summary

Author's Forum

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.