The only thing I know about the Native American is a movie about the western United States.

Marie Kanke of Keio University, Tokyo, Japan—quoted in Japanese Students Get Taste of Oklahoma, the Oklahoman, 8/11/06

The only thing I know about the Native American is a movie about the western United States.

Marie Kanke of Keio University, Tokyo, Japan—quoted in Japanese Students Get Taste of Oklahoma, the Oklahoman, 8/11/06

Polls and surveys

Where do stereotypes come from?

Native American youth say the media has a powerful influence on perceptions of people of color and that they see themselves characterized as "poor," "drunk," "living on reservations," "selling fireworks," and "fighting over land." Whites and African Americans are also seen by these young people as racially stereotyped on TV—"black people are always funny," "white people are all rich and stuff."

"Native American Children Recognize Media Stereotypes," Oklahoma Indian Times, July 1999

"Is there a growing anti-Indian sentiment in the country?"

Yes 76%

No 13%

Unsure 11%

"What do you believe is the primary cause of anti-Indian sentiment?"

Media stereotypes 45%

US government 33%

Systemic racism 22%

Indian Country Today poll of 450 American Indian opinion leaders, 10/18/00

Most people polled (57.4 percent) felt that public schools do not teach enough American Indian history, while 74.3 percent would request more American Indian studies courses from colleges and universities.

About half of these polled American voters, arguably representative of the mass of Americans, get their information on American Indian issues from TV news, some 25 percent from newspapers and 7.7 percent from radio. Even so, they overwhelmingly (71.6 percent) report distrust for the accuracy of the images and characters of American Indians portrayed by Hollywood. The more education, the more distrust. Teachers-educators (78.4 percent) believed this most strongly.

From a Zogby Poll reported in Indian Country Today, 2/14/01

Media is the source

I don't know whether to laugh or cry when people say things like "Indians need to learn to separate entertainment from reality." These people need to learn where the public's misunderstandings and misperceptions come from. If not from the media, then where?

If anyone has an answer other than the media (i.e., stereotypes in the media), I haven't heard it. But let's see what those in the know have to say:

"In day-to-day coverage, minorities often are ignored except for certain categories of stories—notably crime, sports and entertainment," said M.L. Stein in Editor and I. This is a dangerous way of reporting because the media shapes the views of the audience and plays a role in shaping the formation of Canadian minority identities. The media provides an important source of information through which citizens gain knowledge about their nation, and our attitudes and beliefs are shaped by what the media discerns as public knowledge. "The media is responsible for the ways that Canadian society is interpreted, considered, and evaluated among its residents," said Minelle Mahtani in Canadian Ethnic Studies Journal.

Chloe Tejada, Media Column: How the Media Silence Native Americans, 7/2/05

Most non-Indians form their first impressions of Native Americans on the playground. "When little kids play cowboys and Indians," says Robert Thomas, of the University of Arizona, "the Indians are always the bad guys. The cowboys win, the Indians get defeated. Children learn that Indians are bad."

"The Tonto Syndrome," Scholastic Update, 5/26/89

No one illustration is enough to create stereotypes in children's minds. But enough books contain these images—and the general culture reinforces them—so that there is a cumulative effect, encouraging false and negative perceptions about Native Americans.

Council on Interracial Books for Children, Unlearning Indian Stereotypes

Second to religion, I think movies have been the most damaging thing to Indians.

Chris Eyre (Cheyenne/Arapaho), filmmaker, quoted in Indian Country Today, 4/20/02

The media—radio, television, film—is powerful. The messages dominate our thinking, particularly when the viewer has little or no opportunity for firsthand observation. How many Americans see "Indians" anywhere but on the screen? And either way, who is able to distinguish fact from fiction?

Rennard Strickland, Ph.D, Coyote Goes Hollywood, Native Peoples, 1/13/97

The film industry is arguably the most influential entity on the planet and is an almost universally accepted American icon. It shapes our views about almost everything, and American Indians are key players in the history and continuance of American film.

Paul Apodaca (Navajo/Mixton), Apodaca: Hollywood Tragicomedy, Indian Country Today, 11/30/07

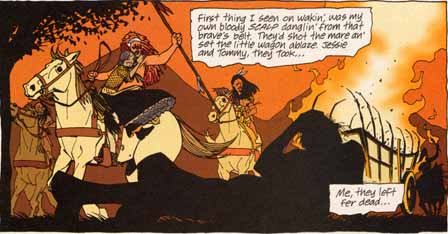

A huge influence on our perception of Indians was moviemaker John Ford. He once quipped he had killed more Indians than the Seventh Cavalry.

"Ford depicted Indians generally as tragic figures on their way to extinction," Strickland says. "Dangerous, vicious people who were savage primitives."

.

.

.

"Surprisingly, even with fewer and fewer Western and Indian films being produced, I find that students in my classes still retain the old movie image. I think this is so because it has no competitive contemporary image out there for younger generations to see."

Rennard Strickland, retired dean of Law, University of Oregon, quoted in Exhibit Preview: The Hollywood Indian, The Register-Guard, 1/26/06

The Native American has been damaged by mass media. The American mythology of cowboys, and the process of moving across the west. The cowboys moved across the west glamorously riding horses, a strong sense of freedom, and conquering the land. In reality, the cowboys moved west by moving the Indians out. There are all kinds of misconceptions about cultures created by Hollywood.

The film Indian is pervasive. No Indian reservation is too distant, no native community too traditional to escape the impact of the movie stereotypes. The ramifications of motion pictures—social and cultural—are everywhere. Indian-authored tales tell of childhoods spent playing cowboy and resenting that the Indians never seem to win. The effect of film can be seen from the smallest details of a child's everyday game of "cowboys and Indians" to the international arena where the movie star President of the United States gives Hollywood-rooted answers to Soviet student's questions about Native Americans.

It is the repetitive regularity of the image in movies that refines and reinforces the societal stereotypes. Hollywood provides an endless parade in which we have "good Indians and bad Indians." In the thousands of individual films and the millions of frames in those films, we have few, if any, "real Indians" who have individuality or humanity; who have families; who lead real lives that differ in marked degree from the lives of other "Indians." Hollywood has tried to squeeze all of these people into these two basic molds. Almost five hundred tribes, bands, and villages are thus reduced to the homogenized film Indian stereotypes.

Rennard Strickland, Ph.D, Coyote Goes Hollywood, Native Peoples, 1/13/97

[As part of a quiz on Indians, moderator Jean Gaddy Wilson] asked participants to write down two positive traits of Indians and two negative traits. Among the positive traits were such things as resourceful, traditional, helpful, knowledgeable of the natural world, survival, spiritual and bravery. Under negatives, responses included words such as alcoholic, lazy, mean, dirty, savages, dishonest, raiders and murderers.

Wilson asked participants where they got their first view of Indians or Native Americans, with the common answer being television and/or movies.

Discussion Centers on Explorers' Interactions with Indians, Marshall Democrat-News, 4/27/04

Beginning with Wild West shows and continuing with contemporary movies, television, and literature, the image of Indigenous Peoples has radically shifted from any reference to living people to a field of urban fantasy in which wish fulfillment replaces reality.

Dr. Cornel Pewewardy (Comanche/Kiowa), Why Educators Can't Ignore Indian Mascots

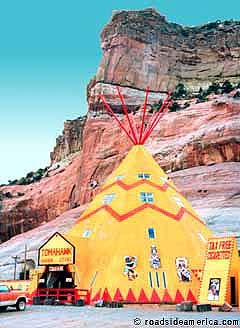

Close your eyes and conjure up what comes to mind when you hear the words "American Indian." No matter your political correctness, the dominant image is probably one of feathers and war paint, bows and arrows, buffalo and teepees, beads and skins, wisdom and warfare.

It is an image derived from adventure movies and childhood books, from sepia-tinged photographs and museum exhibitions, from exploitative television shows and earnest documentaries. Even recent publicity about Indian casinos cannot blemish its iconic power.

Whether the Indian in your image is villain or victim, it is likely some exotic "other," a more primal being somehow in touch with elemental nature which can be a source of savagery and spirituality.

Michael Hill, Challenging Old Views of the American Indian, Baltimore Sun, 8/29/04

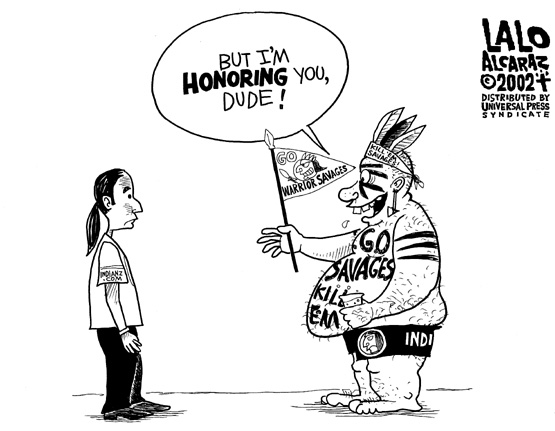

While Little Black Sambo and the Frito Bandito have gone the way of minstrel shows, Indians are still battling a red-faced, big-nosed Chief Wahoo and other stereotypes. No wonder people are confused about who Indians really are. When we're not hawking sticks of butter, or beer or chewing tobacco, we're scalping settlers. When we're not passed out drunk, we're living large off casinos. When we're not gyrating in Pocahoochie outfits at the Grammy Awards, we're leaping through the air at football games, represented by a white man in red face. One era's minstrel show is another's halftime entertainment.

Rita Pyrillis, Sorry for Not Being a Stereotype, Chicago Sun-Times, 4/24/04

How people learn about race

From the Lincoln Journal Star:

Speakers: Media teach racial views

Wednesday, Jun. 5, 2002

By JOANNE YOUNG

Lincoln Public Schools

For those who don't believe multicultural education is needed in public schools, consider this:

• Well before schools were talking about multicultural education, the mass media were teaching multicultural education, however chaotic, confused, semicoordinated, multivocal and unintended.

• The greater the gap between a child's culture and his or her school's culture — frequently white, middle class — the greater the likelihood the student will fail or show low achievement.

Those were the messages from Carlos Cortes and Cornel Pewewardy, speakers at Tuesday's Multicultural Leadership Institute at Lincoln East High School. Lincoln Public Schools Multicultural Office sponsored the conference.

Cortes said the media play a large role in how people perceive each other in America, estimated in the 2000 Census to be 28 percent nonwhite. Children, who generally have their racial attitudes firmly in place by age 9, learn much of what they know about different cultures from television news, talk radio, TV entertainment, movies, newspapers and magazines.

"Whether or not schools and teachers get involved consciously in multicultural education, it will exist in the media," Cortes said. "It's omnipresent, it's ongoing, it's powerful. It affects the ways kids view themselves. It affects the way we view the world around us."

With that in mind, teachers need to prepare young people to deal with information, ideas, values, attitudes and expectations that come to them from the media. They need to help kids be critical consumers.

"That's a big challenge. That's a big change. But the future of a multicultural nation really depends on how we face multicultural education," said Cortes, a professor emeritus of history at the University of California, Riverside, and holder of a master's degree from the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism.

How do ideas about different races, cultures, ethnicities get into people's heads, Cortes asked. Pick a group and see what is being taught every time you see it in the media.

He cited example after example of how the print media use "sleepy" or similar adjectives to refer to Latin American villages and small towns in the United States populated heavily by Latinos. European villages are "quaint" and "picturesque." African villages are "primitive" or "violent."

"This just creeps in all over the place," he said.

He does not accuse the media of bias or racism, but of being lazy and reflexive. The issue is not accuracy, he said. It is frequency and mindless patterns.

"These things are pounded over and over until they are part of kids' minds, their parents' minds, other people's minds," he said. "It happens so surreptitiously we are not aware that these things are building up inside of us."

The media refers to "black on black" crime, but "white on white" crime is never cast in racial terms. A Newsweek headline fanned the dichotomy of "us and them" after Sept. 11 with: "Why They Hate Us, The Roots of Islamic Rage." Another news magazine headline read: "Welcome to Amexica," to reinforce a "They're taking over" fear. And yet another read: "Who Speaks for Blacks? New Fears and Suspicions."

On television, programs based on social situations — families, friends — are frequently segregated as to color. But programs based on work situations mix whites with people of color, giving the impression that it's OK to work together, but not socialize together, Cortes said.

"They say they're not trying to send that message. I don't care, they are sending that message," he said.

Pewewardy, an assistant professor at the University of Kansas School of Education, is a founding member of the National Association for Multicultural Education and consults schools on improving the academic achievement of underrepresented populations. He is Comanche and Kiowa.

He said the "atomic bomb" for indigenous peoples was Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools that dismantled their religions, education, families and communities in an effort to reform their identities into one more European-American.

The ultimate power and control is to define other ethnic groups and control their images, he said. He has written and spoken extensively on the use of Native mascots in colleges and high schools.

Pewewardy teaches future educators how to use multicultural methods in the subjects including math and science. He says teachers have a professional responsibility to eliminate racism in all aspects of school life.

He lauded LPS as is a premier district, a pacesetter, in multicultural infusion in public schools.

"The beauty of multicultural education is upon us," he told the teachers and administrators. "Affirm diversity in everything that you do."

Copyright © 2002, Lincoln Journal Star.

Expert opinion and research

On the psychological harm of stereotyping:

Young children's conceptions of Native Americans often develop out of media portrayals and classroom role playing of the events of the First Thanksgiving. The conception of Native Americans gained from such early exposure is both inaccurate and potentially damaging to others. For example, a visitor to a child care center heard a four-year-old saying, "Indians aren't people. They're all dead." This child had already acquired an inaccurate view of Native Americans, even though her classmates were children of many cultures, including a Native American child.

Debbie Reese, Teaching Young Children About Native Americans

Children are being harmed by these mascots, and not just the Native American children. Once the stereotype is established in a student's mind, it makes it very difficult for children of any race to learn about present day Native Americans. For instance, I have been asked by school children if I still live in a TiPi, and I have been told by a young school aged child that I can't possibly be an Indian, because Indians were all killed a long time ago, and that's why the school mascot is an "Indian"—so Indians can be remembered.

Mike Wicks, MASCOTS--Racism in Schools by State

"Don't you have more important things to worry about?" This statement often is posed by non-Native students at UND to Native students taking part in Fighting Sioux logo discussions.

As a Native educator of 30 years, I can say I have nothing more important to worry about.

I have committed my life to dealing with harmful and negative stereotypes and educating students on my reservation of their culture, traditions, ceremonies and spirituality. As Native people, we experience layer upon layer of stereotypes and images that dehumanize. Eurocentric curriculum and children's literature reinforce stereotypes of the "vanishing Indian," "romantic Indian," "militant Indian" or "drunken Indian." I have seen firsthand how these images, along with poverty or low socioeconomic status, generational trauma and other issues of reservation life contribute to low self-esteem in Native students.

Denise K. Lajimodiere, VIEWPOINT: Racism at Protest Shames UND, Grand Forks Herald, 4/12/06

Almost every Indian person I know of has been horribly impacted by the imposition of the all-pervasive "categorical" stereotypical classification upon their basic sense of humanity--so much so that I feel quite safe in declaring that all Indian people suffer a unique form of self-esteem deficiency based solely on the widespread mayhem that Indian stereotypes have caused us since before the Boston Tea Party.

Melvin Martin (Lakota), Identifying Indians with Stereotypes, 2/28/09

Certainly, there are other areas of life that need to be addressed and which may appear to be more urgent. Crime, substance abuse, incarceration and many other ills are relevant problems that require solutions. However, the root of many, if not most, of these is the lack of self-esteem our children experience. Over the past five centuries our religions, our languages, our ceremonies, the totality of our cultures, have been violently suppressed. Today, youth learn about Indians through distorted depictions in advertising, by watching television and movies, and through the symbols associated with athletic mascots. Not many years ago, some of our friends overheard reservation children, while watching a Hollywood western, voice the hope that someday they could meet a "real" Indian. This situation must change, because without a healthy self-image, our youth are condemned to lives of continuing social and emotional problems.

Jonathan B. Hook, Ph.D., president, American Indian Resource Center

Minority groups are regularly excluded and marginalized, and the dominant culture is reinforced as the norm. As a result, not only does the audience believe that minorities are bad people, minorities themselves feel excluded from their Canadian identity and believe that they are indeed inferior people. "Negative depictions of minorities teach minorities in Canada that they are threatening, deviant, and irrelevant to nation-building; they effectively serve to instill inferiority complexes among minorities; there are few positive role models," says Mahtani.

Chloe Tejada, Media Column: How the Media Silence Native Americans, 7/2/05

I point to the American Indian Mental Health Association of Minnesota's 1992 position statement supporting the total elimination of Indian mascots and logos from schools. "As a group of mental health providers, we are in agreement that using images of American Indians as mascots, symbols, caricatures, and namesakes for non-Indian sports teams, businesses, and other organizations is damaging to the self-identity, self-concept, and self-esteem of our people. We should like to join with others who are taking a strong stand against this practice."

Dr. Cornel Pewewardy (Comanche/Kiowa), Why Educators Can't Ignore Indian Mascots

Laboratory research readily demonstrates that when one group of experimental subjects is directed to inflict pain or harm to members of another experimental group of subjects, the "victim" group is routinely derogated and dehumanized verbally by the "oppressor" group (Davis & Jones, 1960; Glass, 1964; Worchel & Andreoli, 1978). By developing such negative attitudes toward their own victims, "exploiters can not only avoid thinking of themselves as villains, but they can also justify further exploitation" (Franzoi, 1996, p. 394).

Negative images and attitudes toward American Indians have served precisely the same function: To protect the historical oppressors from a sense of guilt over the atrocities committed against Indians and to justify further exploitation. Indians as well as other ethnic minorities in America today "become acutely aware of the [negative] evalutions of their ethnic group by the majority white culture" (Santrock, 1997, p. 402). In a study of identity formation among minorities, Phinney (1989) reported that African Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanics, and American Indians all suffer from negative stereotypes imposed by the dominant American culture, which denigrates precisely those aspects of ethnic culture that minorities take pride in.

Research on the adverse outcome of such negative stereotypes on the functioning of minorities in America is voluminous (see Spencer & Dornbusch, 1990, for an overview). Negative appraisals of non-whites in America lead to perceptions among minorities that employment avenues are cut off and that success is out of their reach.

David P. Rider, Ph.D., Stereotypes/Discrimination/Identity

Native Americans have the highest high school drop out rates, the lowest rates of college-age youth enrolled in colleges or universities, and the highest rates of teen suicide in the entire country. It has been argued by statisticians that the suicide rate of Native Americans is about 75 percent higher than the national average. Other self-destructive activities are also commonplace, such as alcoholism and other substance abuse. The poor self-image Native Americans have as a people [has] contributed to these tragedies. That poor self-image is a direct consequence of the persistent misrepresentation of Native Americans in popular culture, by the media, athletic teams and organizations, and the refusal of the mainstream public to acknowledge that these are indeed a major root cause of all the larger problems.

H. Mathew Barkhausen III, 'Red Face' Does Not Honor Us, Snag Magazine, 2/1/05

Study proves harm

A study demonstrates how being deemed inferior hurts people.

Black people's reality rebuffed

By Wendi C. Thomas

Sunday, November 11, 2007

The truth: It is nearly impossible, even for the most anti-racist white people, to truly understand how a lifetime of discrimination digs into your soul, how the disrespectful denials of your truth can make you insane.

I don't want sympathy, just the respect that I know my reality more than you ever could. More than anyone else I've seen, Elliott makes this clear.

She's the creator of the legendary "Brown Eyes, Blue Eyes" experiment. She tried it first on her third-grade classroom in the all-white town of Riceville, Iowa, on April 5, 1968, the day after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Dividing her class by the color of their eyes was her attempt to show her students what it feels like to be assigned to the underclass.

The third time she segregated her class by eye color was in 1970 and the lesson was videotaped.

On the first day, she told the blue-eyed students that they were better, smarter, would get more time on the playground and could get seconds at lunch. The brown-eyed students had to drink from a cup, not the water fountain, and would endure unwarranted criticism of their behavior.

Almost instantly, the brown-eyed children began to wither. Their second-class citizenship, just hours old, had begun to affect their performance in class. And the blue-eyed students reveled in their privileged status. "I felt like I was a king," one of the blue-eyed boys said, "like I ruled them brown-eyes. Like I was better than them. Happy."

Contrast that with the despair of a brown-eyed student: "The way they treated you, it felt like you didn't even want to try to do anything."

The next day, Elliott told her students she'd been mistaken, that brown-eyed students were better, smarter. And the students who had been discriminated against the day before adopted the attitudes of the oppressor. When they were the lower class, the brown-eyed children struggled for more than five minutes to get through a flash-card exercise; when they were on top, they whizzed through the cards in under three minutes. "The only thing that had changed was that now, they were superior people," Elliott said on the tape.

She'd created a little America in her classroom, one in which the discrimination experienced by people of color could not be denied, not even by third-graders.

That transformative aha moment happens for almost all of the adults who have participated in the "Brown Eyes, Blue Eyes" exercise Elliott has conducted around the world in the decades since.

How resistant are some white people to her message? Very. She's had a knife pulled on her, one white man hit her and others have threatened her life.

Psychologists agree

From the American Psychological Association, 10/18/05. Note the reference to "a growing body of social science literature that shows the harmful effects of racial stereotyping and inaccurate racial portrayals."

APA Calls for the Immediate Retirement of American Indian Sports Mascots

Such Sports Mascots Promote Inaccurate Images and Stereotypes and Negatively Affect the Self-Esteem of Young American Indians

WASHINGTON, DC—The American Psychological Association is calling for the immediate retirement of all American Indian mascots, symbols, images and personalities by schools, colleges, universities, athletic teams and organizations, the Association announced today.

APA's action, approved by the Association's Council of Representatives, is based on a growing body of social science literature that shows the harmful effects of racial stereotyping and inaccurate racial portrayals, including the particularly harmful effects of American Indian sports mascots on the social identity development and self-esteem of American Indian young people.

"The use of American Indian mascots as symbols in school and university athletic programs is particularly troubling," says APA President, Ronald F. Levant, EdD. "Schools and universities are places of learning. These mascots are teaching stereotypical, misleading and, too often, insulting images of American Indians. And these negative lessons are not just affecting American Indian students; they are sending the wrong message to all students."

Psychologist Stephanie Fryberg, PhD, of the University of Arizona, has studied the impact of American Indian sports mascots on American Indian students as well as European American students. Her research shows the negative effect of such mascots on the self-esteem and community efficacy of American Indian students.

"American Indian mascots are harmful not only because they are often negative, but because they remind American Indians of the limited ways in which others see them," Fryberg states. "This in turn restricts the number of ways American Indians can see themselves."

The issue of the inappropriateness and potential harm of American Indian mascots is broader than the history and treatment of American Indians in our society say many psychologists who have studied issues of race in America. Such mascots are a contemporary example of prejudice by the dominant culture against racial and ethnic minority groups, according to these scholars.

Psychologist Lisa Thomas, PhD is a member of the APA Committee on Ethnic and Minority Affairs which drafted the Indian mascot resolution.

"We know from the literature that oppression, covert and overt racism, and perceived racism can have serious negative consequences for the mental health of American Indian and Alaska native (AIAN) people. We also need to pay careful attention to how these issues manifest themselves in the daily lives (e.g., school, work, traditional practices, and social activities) and experiences of AIAN individuals and communities. As natives, many of us have had personal and family experiences of being the target of frightening, humiliating, and infuriating behaviors on the part of others. This resolution makes a clear statement that racism toward, and the disrespect of, all people in our country and in the larger global context, will not be tolerated," Dr. Thomas states.

Full text of the resolution can be found at http://www.apa.org/releases/ResAmIndianMascots.pdf

For more information or interviews:

John Chaney, PhD Oklahoma State University (405) 744-6027

Stephanie Fryberg, PhD University of Arizona (520) 621-5497

Lisa Thomas, PhD University of Washington (206) 897-1413

Related links

Indians and poor self-esteem

The painful reality

If anyone thinks these leaders, artists, academics, and researchers aren't in touch with what's really happening in America, they should think again. These people are talking about real problems, not hypothesizing about theoretical ones. Here's the proof: people who have endured the psychological pain and confusion we're talking about.

In my short lifetime — I'm only 42 years old — I have experienced on occasions too numerous to count encounters with non-Indians who have asked me, "What was it like to grow up living in a teepee?"

And it never fails that once I have responded to the teepee question I always get the follow up, "But I thought all Indians lived in teepees."

Sebastian "Bronco" LeBeau (Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe), What an Indian Is Not, 6/13/01

As a young girl trying to establish an identity, I absorbed these mass media images about American Indians. I devoured books such as The Indian in the Cupboard and though no one in my family watched sports, I sought out and learned the "Tomahawk Chop," all for mainstream cultural validation. It was no different than looking to the mass media for society's ideals on beauty and athleticism, except I couldn't find any American Indians there so I had turn to these other representations.

Darla M. Wiese, Chief Is Reflection of American Indian Education, Quad-Cities Online, 9/18/06

Dan Ninham's three children ask questions when they see the Eaton High School mascot caricature of an American Indian. The questions sting Ninham, a Greeley resident who is a member of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin: Do we look like that? Should we dress like the Indian in the Eaton logo when we go to the Denver Pow Wow? Is our nose part of our forehead?

"In Eaton, Fightin' Reds Mascot Has Come Under Fire," Greeley Tribune, 1/20/02

[L]ast year I remember my 5-year old daughter coming home very excited and saying she learned how to be "Indian" in school. At first I was shocked and upset because she's Navajo, I then decided to find out what she was talking about. I asked her, "What is it to be Indian?"

She replied, "We put paint on our faces, wore feathers in our hair and did Indian dances." I asked, "Who showed you the Indian dance?" She answered, "My teacher." I said, "Show me the dance." She started prancing around in circles — it was cute.

Eugene Tapahe, Indian Mascots Affect More than Sports, Navajo Times, 1/29/06

[Indians] have a way of surviving. But it's almost like Indians can easily survive the big stuff. Mass murder, loss of language and land rights. It's the small things that hurt the most. The white waitress who wouldn't take an order. Tonto, the Washington Redskins.

Sherman Alexie (Spokane/Coeur d'Alene), The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven

On the reservation, he and others would play cowboys and Indians because they were American, too, he says. Watching Westerns, he would root for John Wayne, he adds.

"I distinctly remember doing that because I didn't recognize those Indians; I wasn't those Indians; I wasn't running around in a loincloth. I wasn't vicious. I wasn't some sociopath with war paint." Alexie says.

Interview with Sherman Alexie, CBSNews.com, 3/20/01

My elementary school is known as Cotaco. Its symbol is a large native american head. Our mascot when someone puts him on is grossly disfigured. He does not even make us look human. I remember one time when my high school had a pep rally the principle announced that since the school we were playing that day had an indian mascot the theme of the pep rally would be "attack those indians!" At that two of my friends who frequent pow wows with me dive under their desks shouting "Don't attack us! pleaaassseee!" Just like them to shed humor on something that makes them uncomfortable.

It is not uncommon for me to suffer many derogatory and degrading remarks many done in so called good nature including by teachers. I have developed a system of explaining to these people and teachers that even though it may be meant in good humor it is still hurtful and considered a form of prejudice. Some abided by my wishes some become defensive and others continue to make such remarks just to eat at me.

Kristen Dross (Echota Cherokee/Indian), age 18, 4/6/01

"I went back to school in the fall…We read a history book about "the savages." The pictures were in color. There was one of a group of warriors attacking white people – a woman held a baby in her arms. I saw hatchets, blood dripping, feathers flying. I showed the picture to the Sister. She said, "Rose Mary, don't you know you're Indian?" I said, "No, I'm not." She said, "Yes, you are." I said, "No!" And I ran behind a clump of juniper trees and cried and cried." —Rose Mary (SHINGOBE) Barstow, (Ojibwe), 1976

H. Mathew Barkhausen III, 'Red Face' Does Not Honor Us, Snag Magazine, 2/1/05

After listening to her sob uncontrollably for an hour and a half, Barry Landeros-Thomas finally calmed his daughter down enough for her to explain to him why she came home from school in tears.

During recess, a couple of boys danced around her singing a Pocahontas song, "Savages! Savages! Barely even human," he said.

"Native Americans Face Stereotypes," The Post (Ohio University), 11/1/01

Daniel Green, a Diversity Studies professor at the University of Wisconsin, La Crosse, Wis., who spoke at an early morning meeting in UND's Lotus Mediation Center, agrees.

"What goes into the mind comes out in the form of behavior," Green said.

He said that cultural stereotypes have a negative impact on native and non-native American people alike and gives them erroneous information about Indian culture and traditions.

It also promotes low self-esteem in the developing minds of Indian teenagers who are often cast out and grow up thinking that they are not good enough compared with mainstream society, Green said.

"I know that because I used to be one of them," he said.

Elisa L. Rineheart, "Tribes Protest Use of Fighting Sioux Nickname, Logo," Grand Forks Herald, 3/27/05

[M]any American Indian children start life with less-than-glowing self-images, images reinforced by the realization that their ancestors were driven from their homes by European settlers, images reinforced by silly cowboy movies, images reinforced by their marginal role in society.

Even Begay, who did a postgraduate year at exclusive Phillips Exeter Academy and earned a pre-med degree from an Ivy League college, felt he was different from mainstream America as he grew up in Shiprock.

"It wasn't the best image," he said. "It definitely took me a long time to accept that I was part of this minority with this history of subjugation and domination. I wasn't proud."

Chris Simmons, Are Native American Nicknames Appropriate? (An Opinion Column), Daily News-Record, 9/16/05

Our youth face the consequences of public ignorance every day. Some of the taunts I remember: "say something in Indian", "why don't you do a rain dance", "hey chief", "ug", "you ought to be grateful for all we gave you", "you are so lucky the Pilgrims saved you," "you all get free money and don't have to do anything for it," "you don't pay taxes like the rest of us", ad infinitum. All of which were constant reminders that I was some kind "object", a curiosity to be separated from the "normal" people, not a person. The questions for Indian Country should include: How does this ignorance continue to work on the psyche of American Indian youth? How is this connected to the fact that American Indian youth drop out of school, commit suicide, and become substance abusers at higher rates than any other group?

Mike McLaughlin (Winnebago), The Need for American Indian Librarians, Native American Times, 10/12/2005

More psychological effects

Besides acknowledging the fact that television media often offers negative stereotypical portrayals of individuals belonging to certain racial and/or ethnic groups such as African-Americans and homosexuals, social psychology goes further by examining the direct implications of these mostly negative images. One of these implications is the notion of stereotype threat, the risk of confirming a negative stereotype about one's group as self characteristic. As an individual is constantly exposed to negative images of his/her racial or ethnic group, this person begins to internalize the same social and personal characteristics of these images.

Numerous psychological studies have examined effects of stereotype threat in areas such as standardized tests, and athletic performance. For example, the commonly held assumption that women are less skilled in mathematics than men has been shown to affect the performance of women on standardized math tests. When female participants were primed beforehand of this negative stereotype, scores were significantly lower than if the women were led to believe the tests did not reflect these stereotypes (Spencer & Steele, 1997).

Going hand in hand with the idea of stereotype threat, the negative television portrayals have a direct correlation with the effects of the self-fulfilling prophecy. Although not in the realm of primetime television, channels such as MTV offer blatantly stereotypical images of African-Americans and women that greatly affect the young viewers who, in turn take these images to heart. Rap videos lead young black males to internalize a positive image of Black culture that emphasizes the degradation of women as objects, the lurid appeal of money, and material possessions, as well as the endorsement of alcohol and drug use. With constant exposure to these images, it is no surprise that we have seen many instances of young black men attempting to emulate these images through overt behaviors such as drug use, domestic violence, and criminal activity.

In terms of primetime television, an issue that has been in the news recently is how many women are seen on television represented by unrealistically thin images of many prominent actresses in Hollywood. Shows such as Ally McBeal and Friends have generated a great amount of controversy over how these images affect a number of women viewers into aspirations of attaining these virtually unattainable bodies. While television images provide only one aspect of our culture that leads women to desire these traits, it deserves the most attention because of how pervasive television has become in American society. The negative impact of these media trends is seen in the many women who suffer from eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia in hopes of reaching a slim figure.

One Native correspondent of mine compared seeing a mascot like Chief Illiniwek to having post-traumatic stress disorder. She said it reminded her of being taunted as a child for being Indian, and caused her great anguish and sadness. Hmm...sounds like a problem to me.

As these quotes indicate, the problem is more than an abstraction. It goes beyond creating biased impressions of minorities. Stereotyping causes real harm to people. It harms the physical and mental well-being of the minorities being labeled.

It should be obvious that wrongly labeling people is harmful. Anyone who's ever been called a "dunce," "weakling," or "slut" can attest to that. The hurt feelings last long after the source is gone. People often remember the pain of name-calling all their lives.

If you're called something often enough, you tend to internalize feelings of worthlessness. That mental anguish can cause physical impairment is extremely well-documented. You also tend to "act out" to defy your tormentors, which can lead to rejection or punishment. So bad "feelings" can have both physical and social consequences.

Research also confirms that names can hurt you. Consider the studies in which students were arbitrarily divided into two classes of people (e.g., guards and prisoners). Within a matter of days, the students were playing their roles in dead earnestness. And those in the "lower" class were experiencing genuine feelings of persecution and inferiority.

More physical effects

To reiterate, stereotyping can cause physical as well as psychological pain. From the Wall Street Journal:

July 15, 2007, 5:21 pm

Research into the physical effects of racism on its victims could help explain a disparity in health across races and reframe racism as a health issue. Health experts have long blamed racial disparities on social forces, linking higher rates of disease and death among African-Americans to joblessness, unsafe housing, and other inequities. This round of research, which scientists stress is preliminary, seeks to establish if racism itself plays a role in the disparity. In more than 100 studies on the subject, most of them published since 2000, some patterns have been established, reports Madeline Drexler for the Boston Globe.

Discrimination seems to act as a source of chronic stress the same way that marital conflict or strains at work do, increasing the stress hormone cortisol, raising blood pressure, and suppressing the immune system. High stress also has been linked to unhealthy behaviors such as overeating or smoking. When African-Americans are shown a racially provocative scene on television—a white store clerk racially insulting a black customer, for example—their blood pressure and heart rates rise. It also takes a longer time for those indicators to return to normal than usual. A yet-to-be-published study by Elizabeth Brondolo, a psychologist at St. John's University in New York found that racism experienced in the day led to elevated blood pressure at night, suggesting the body can't turn off its stress response.

When Jules Harrell, a Howard University psychology professor, saw a photo of the Rutgers University women's college-basketball team players after Don Imus labeled them with a racial epithet he was moved by their reserve. "The expressions on their faces. All I could think was, 'Good God, I'd hate to see their cortisol levels.'" Studies have shown that the stress of suppressing the inner turmoil caused by racist encounters can itself lead to ill effects.

Skeptics say the research lacks an objective definition of racial discrimination. What seems like racism might have a more benign motivation and these studies overly rely on their volunteers' accounts of racial discrimination. Scholars in the field say they are following the same procedures used in studies of depression, anger, and post-traumatic disorder. They have refined their questionnaires to look out for moods such as depression or hostility, which encourage people to interpret acts as racist.

— Robin Moroney

Here are some of the symptoms of stress:

Health Problems Linked to Stress

* Heart attack

* Hypertension

* Stroke

* Cancer

* Diabetes

* Depression

* Obesity

* Eating disorders

* Substance abuse

* Substance abuse

* Ulcers

* Irritable bowel syndrome

* Memory loss

* Autoimmune diseases (e.g. lupus)

* Insomnia

* Thyroid problems

* Infertility

Beyond pain and suffering

Not only does stereotyping harm the victims, it arguably harms the victimizers. Suppose you're a "redneck" or "hillbilly" or "white trash" who believes you're better than a minority. Your prejudices may make you feel good, but they also help keep you down. Instead of finding common cause with people who might agree with you, you end up fighting them. It's the epitome of a "divide and conquer" strategy.

Stereotypes also harm society as a whole. They reinforce our dominant cultural attitudes—about race, gender, class, religion, and other defining traits. They allow the people in power to remain in power. If Indians or other groups are deemed inferior or worthless, we can take their possessions and rights and not feel bad about it.

First, some background on how the media influences racial perceptions in general:

For centuries, art has been used for less than honorable purposes. Some of the earliest examples of art that has been used to purposely incite violence against an ethnic minority are found in anti-Semitic political cartoons in Europe. In the U.S., early examples include the extremely grotesque caricatures of African Americans in an effort on the part of the dominant Anglo-American society to solidify in the minds of the public that they were not "people," so denying them basic human rights was perfectly permissible. In early cartoons produced by major animation houses such as Warner Brothers, the way in which African Americans were portrayed was a reflection of an attitude of intense racial hatred deeply ingrained in American society at the time. That is why nothing was thought to be "wrong" with it.

Perhaps one of the most devastating examples of how effective these racial smear campaigns were is that of the Japanese internment during World War II. Japanese Americans were rounded up and forced into concentration camps because they were believed to be willing to attack the United States from within. Despite the fact that a large number of them served in World War II on the side of the U.S., their service during the war was not enough for the government to release their families from the Japanese concentration camps. How on earth could an entire population have been motivated to perceive the Japanese Americans in such an extraordinarily negative light? The answer of course is in the despicable propaganda campaign of political cartoons, films, and other forms of racist media.

H. Mathew Barkhausen III, 'Red Face' Does Not Honor Us, Snag Magazine, 2/1/05

A figment of the imagination

Next, let's see how this applies today. As several people have said, if the media isn't stereotyping Indians, it's ignoring them. That leaves the Indian as a colorful and mysterious image, a figment of the imagination, and nothing more. The result is confusion and uncertainty in the minds of the public.

As we walked into an exhibit, a large screen flashed images of American Indians. One was a construction worker, another a young professional and another a farmer. As the images were displayed a voice overlay said something to the effect of "Everyday you may come in contact with an American Indian and not even know it. They're workers, teachers. . ." etc.

My first thought was, "Um, duh?"

My second thought was a little heavier. I remembered doing research a year earlier for a college paper about the Washington Redskins and the sports mascot debate. For many people, the portrayals of American Indians in movies, television, halftime shows, books and cartoons may be the only "contact" they ever have with the American Indian culture. The context of the stories told about American Indians is almost always in the past tense, in a past time, contributing to a subconscious thought that American Indians no longer exist and/or are part of fairy tales.

That's why the exhibit at the museum felt compelled to explain to its visitors that American Indians exist today — you just might not recognize them because they're in hard hats and suits.

Darla M. Wiese, Chief Is Reflection of American Indian Education, Quad-Cities Online, 9/18/06

Beginning with Wild West shows and continuing with contemporary movies, television, and literature, the image of Indigenous Peoples has radically shifted from any reference to living people to a field of urban fantasy in which wish fulfillment replaces reality.

So-called Indian mascots reduce hundreds of Indigenous tribes to generic cartoons. These "Wild West" figments of the white imagination distort both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children's attitudes toward an oppressed—and diverse—minority. Schools should be places where students come to unlearn the stereotypes such mascots represent. The Indigenous portrait of the moment may be bellicose or ludicrous or romantic, but almost never is the portrait we see of Indian mascots a real person. Most children in America do not have the faintest idea that "Indigenous Peoples" are real human beings.

Dr. Cornel Pewewardy (Comanche/Kiowa), Why Educators Can't Ignore Indian Mascots

The prevalence of fake, stereotypical, and negative images of American Indians is a contributing factor to these crime rates. The ability to objectify an entire race of people and to amalgamate them under the singular false image of the dancing, prancing, tomahawk-chopping, savage warrior contains within it the foundation for physically assaulting the individuals to whom one ascribes these characteristics. When a people are only stereotypes they are not real.

Dr. Cornel Pewewardy (Comanche/Kiowa), et al., Of Polls and Race Prejudice: Sports Illustrated "Errant 'Indian Wars'"

American Indians seem an enigma to most other Americans. The images portrayed in the movies, whether of noble red man or bloodthirsty savage, recall the stereotypes of western history. Newspaper stories dealing with oil wells, uranium mines, land claims, and the occupation of public buildings and reservation hamlets almost seem to speak of another group altogether and it is difficult to connect the two perceptions of Indians in any single and comprehensible reality.

Vine Deloria Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux), American Indians, American Justice

Native American scholar Vine Deloria wrote that of all the problems facing Indian people, the most pressing one is our transparency. Never mind the staggering suicide rate among Native youth, or the fact that Indians are the victims of violent crimes at more than twice the rate of all U.S. residents — our very existence seems to be in question.

"Because people can see right through us, it becomes impossible to tell truth from fiction or fact from mythology," he wrote. "The American public feels most comfortable with the mythical Indians of stereotype-land who were always THERE."

Rita Pyrillis, Sorry for Not Being a Stereotype, Chicago Sun-Times, 4/24/04

More so than any other group, American Indians are portrayed in popular culture as a people of the past, and as a result, the material conditions of the lives of Native peoples today are largely ignored.

Bruce A. Goebel, "Reading Native American Literature"

America prefers Tonto-esque "good Indians" located in the far off past where Indian rebellion can be ideologically managed. Real Indians with real culture and real grievances are generally taboo.

Brian McKenna, Giving Thanks to America's Indians: Native Resurgence Spurs Hope, 11/24/06

Media image is especially crucial because it is that image that looms large as non-Indians decide the fate of Indian people. If non-Indian decision-makers continue to view native people as savage survivors or happy hunters on the way to extinction, the policy is different than it would be if decision-makers saw beyond the stereotype.

Rennard Strickland, retired dean of Law, University of Oregon, quoted in Illiniwek Becomes a Controversy in Oregon, Too, Native Times, 12/13/05

In the past century, he argues, Hollywood's Indians have had a profound influence on the lives of real Indians. That's because the movie version has been the main source of information, he says, for the non-Indian lawmakers who have decided the fate of real indigenous people.

.

.

.

"Very much of what we do with regard to Indians grows out of how Indians are portrayed in the media," he says. "Most people's image of the Indian is related to what one sees on the screen, whether in TV or movies. And most decisions (about Indians' lives) are made, under the trust relationship, not by Indians themselves but by non-Indians."

Rennard Strickland, retired dean of Law, University of Oregon, quoted in Exhibit Preview: The Hollywood Indian, The Register-Guard, 1/26/06

Somebody is benefiting by having Americans ignorant about what non-European Americans are doing and what they have done; what European Americans have done to them.

Wendy Rose (Hopi/Miwok), quoted in "Who Gets to Tell Their Stories?," New York Times Book Review, 5/3/92

We still suffer from the rage to get Indian life under control: to classify, explain and defuse it, to make it safe.

James R. Kincaid, "Who Gets to Tell Their Stories?," New York Times Book Review, 5/3/92

Reinhardt says that any stereotype does damage. "Even as they change over time and become ostensibly positive, they were still limiting in their own way by pigeonholing Indians ... ," Reinhardt says.

"So today's Indian people still have to battle these stereotypes. What some of them have voiced to me on numerous occasions is that they continue to fight to say, 'We are still here.'"

Akim Reinhardt, historian at Towson University, quoted in Challenging Old Views of the American Indian, Baltimore Sun, 8/29/04

Power and control

Finally, let's get to the heart of the matter. Why would mainstream society want to sow confusion about Indians or spread misinformation about them? How does mainstream society benefit from ignoring or stereotyping minorities, especially Indians?

It's really advantageous for...power people not to know anything about the culture. [If they know] they're going to have to do something about the Indian situation.

James Welch (Blackfeet/Gros Ventre), quoted in "Who Gets to Tell Their Stories?," New York Times Book Review, 5/3/92

[If people learned about Indians, they] would have to say, yes, and agree and press the Supreme Court and US Congress to give the Black Hills back to the Lakota people...to say, yes, the Native American people do own Arizona.

Simon Ortiz (Acoma), quoted in "Who Gets to Tell Their Stories?," New York Times Book Review, 5/3/92

Clark said that by fabricating these symbols and images, it empowers white supremacy because these images and symbols create boundaries between American Indians from non-American Indian.

It recreates the American Indians' actual identity by replacing it with the colonizers' stereotypical idea of the group and deviates from their identity and culture, Clark said.

Clark said it produces antagonistic communities and separates groups further. It leaves generations with a reminder of what's "bad" about American Indians, such as stereotypes of them being "savage," deviates from their true history and erases their misfortunes.

Rebecca Persons, quoting Anthony Tyeeme Clark, American Indian Studies Program assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Speaker Opposes Stereotypes of American Indians in Entertainment, 4/24/07

I think a similar power dynamic is at the core of white resistance to the simple act of dropping nicknames such as Fighting Sioux: Indians don't get to tell white people what to do. Why not? Polite white people won't say it in public, but this is what I think many white folks think: "Whites won and Indians lost. It's our country now. Maybe the way we took it was wrong, but we took it. We are stronger than you. That's why we won. That's why you lost. So, get used to it. You don't get to tell us what to do." I think for white people to acknowledge that we don't have the right to use the name and logo would be to open a door that seems dangerous.

Why should Indians have the right to make the decision over how their name and image are used? Because in the absence of a compelling reason to override that right, a person or group of people should have control over their name and image. That's part of what it means to be a person with full humanity. And in this case, the argument for white people giving Indians that power is intensified by the magnitude of the evil perpetrated by whites on Indians.

To acknowledge all that is to acknowledge that the American nation is based on genocide, on a crime against humanity. The land of the free and the home of the brave, the nation that was born as the vehicle for a new freedom, rests on the denial not only of freedom, but of life itself, to a whole group of people — for the crime of getting in the way of what the European invaders wanted for themselves, the land and its resources.

Robert Jensen, The Past & Human Dignity: What the "Fighting Sioux" Tells Us About Whites, 10/14/03

Power and Control

I believe that the hidden agenda behind Indian mascots and logos is about cultural, spiritual and intellectual exploitation. Therefore, the real issues are about power and control. These negative ethnic images are driven by those that want to define other ethnic groups and control their images. To me, power and control is the ability to make you believe that someone's truth is the absolute truth. Furthermore, it's the ability to define a reality and to get other people to affirm that reality as if it were their own. Remember that media commercials are carefully designed and expensively produced to stereotype groups and helps us, as consumers, "realize" we are far less than we should be. This is an additive systemic approach to power and control.

Social Construction of Reality

Furthermore, I contend that American racism as we inherit it today is a social construction of reality. Prior to Columbus, the world functioned for millennia without the race construct as we understand it today. Therefore, we must understand that racism is the primary form of cultural domination in the United States over the past four hundred years. It is cultural construction by social scientists and other students of group life as well as the mass media. Together with schools, legal systems, and higher education institutions, these forces participate in a major way in legitimizing and reifying the invalid construct. Consequently, the race construct is now internalized by the world's masses. All these voices together have helped to perpetuate this ignorance and distortion.

Dr. Cornel Pewewardy (Comanche/Kiowa), Why Educators Can't Ignore Indian Mascots

The question of mascots is significant for Native Americans. It transcends sports and entertainment. It influences law. It dominates resource management. It profoundly impacts every aspect of contemporary American Indian policy and shapes both the general cultural view of the Indian as well as Indian self-image. No groups other than the Indian face the legal situation in which their land, as well as their economic, political and cultural fate, is so completely in the hands of others. That is so because of the way in which substantial tribal resources are held "in trust," with the management and regulation, if not always operation, resting with the federal government as "trustee." The result is that the non-Indian in the U.S. Congress and in the executive branch control the fate of Indian peoples and their resources when they legislate and administer practices and policies.

The Indian image is, therefore, an especially crucial and controlling one because it is that image (often reflected in mascots like the Redman) which looms large as non-Indians decide the fate of Indian people. If the non-Indian decision makers continue to view native people as dinosaurs, as redskins or warriors, as happy hunter on the way to extinction, the policy will be different from what it would be if the decision-makers saw beyond the mascot and the stereotype.

Rennard Strickland, Changing Mascots Doesn't Signal Failure, Lack of Honor, Muskogee Phoenix, 9/14/06

Framing the issues and thus controlling the debate is it in a nutshell. If Indians are invisible, their problems don't exist. If they're visible only as mascots and museum pieces, their problems don't matter. It's only when we see them as full, complex people that we begin to take their problems seriously.

For more on how the white majority benefits from prejudice and stereotyping, see Systemic, Not Aberrant.

What to do about it

The solution to the problem of stereotyping is to change the images in the public consciousness. Frame the issues from a Native perspective:

Few congressional members know the Indian life and culture, except for negative articles, Mankiller said.

There are dangerous stereotypes. We have to tell our own stories.

If we don't frame the issues, someone else will frame the issues for us.

Wilma Mankiller (Cherokee), quoted in Tribal Leader Urges Students to Tell Their Stories, Associated Press, 6/16/05

The future preservation and prosperity of American Indians will not be decided in the halls of Congress or state legislatures, nor will it be adjudicated ... (at) the U.S. Supreme Court," he told an audience of more than 50 people. "It will be decided by the voting public in the court of public opinion.

Anthony Pico, former chairman of the Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians, quoted in Tribal Leaders Worry About 'Wealthy Indian' Image, 9/25/07

"Perception is reality." "Truth is an ally." "Perception becomes public policy, always." These important messages are worth repeating and should become the mantra for all Indian nations.

Tell Your Truth to Media, Indian Country Today, 10/4/07

"Perception is as much of a threat as anti-sovereignty legislation. We have to regain control of our image," said Mankiller, who in 1985 became principal chief of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, the second largest tribe with more than 140,000 enrolled members and an annual budget of $75 million.

Tribal Leader Urges Students to Tell Their Stories, Associated Press, 6/16/05

Proper and realistic representation in the media is crucial for the protection of American Indian peoples' inherent and treaty rights. The way situations and issues are covered — how the media comes to interpret Indian realities — increasingly drives the making of public policy. Issues that can help or wreak havoc on American Indian tribal life are decided not only by reason and precedence, but too often by the clamor of negative public attention.

Media Impact on American Indian Public Policy Is Important Strategic Key, Indian Country Today, 1/9/06

As media consumers, Indian people are in a particularly harmful position. We consume the thoughts of others about ourselves and the world. The media has, for its own purposes, created a false image of the Native American. Too many of us have patterned ourselves after that image. It is time now that we project our own image and stop being what we never really were.

Gerald Wilkinson, National Indian Youth Council, "Colonialism Through the Media," The Indian Historian (Summer 1974)

More on Native stereotypes (how people learn them, how they cause harm, etc.)

Miseducating our children

How stereotypes affect real people

Girl cries over stereotypes

Students can't overcome stereotypes

Are stereotypes decreasing?

How things have changed

Cub Scouts and Go Go Gophers

Another Indian states the obvious

Whoopie pies and Eskimo ice cream

Learning about Indians in school

The greatest threat to Indians

Media images "dominate our consciousness"

Pop culture is the source

But stereotypes can hurt you

Stereotypes: The worst Native problem

Related links

Quotes on Native stereotyping

The trouble with stereotyping...and what to do about it

Stereotype of the Month contest

Readers respond on whether stereotypes come from the media

"[T]hat the media instead purposefully are teaching stereotypes ranks with the most hysterical and syllogical conspiracy theories yet known!"

"[Taunting or 'Tontoing'] is blamed on the media alone, and not on parents or homelife or schools or churches or communities or even 'the dominant culture.'"

"[F]amilial contact, community contact, school contact, church contact, and cultural contact ALSO ARE MEDIA!!!"

"Um, did that say, 'Bad Stereotypes Can Harm You'? [That] means that there are GOOD stereotypes which must be GOOD for you!"

"Racist and stereotypical ideas are learned at home and in the communities gated or otherwise and in schools and even in church."

If media alone taught racial biases and stereotypes, the result would be "a uniform, homogeneous facet of American culture that contained identical concepts."

"Racial bias and cultural stereotypes have been communicated by families, schools, churches, communities, and cultures long before there were any [mass] media."

"If media were the teachers, everybody's ideas would be the same no matter the race or ethnicity or geographical area, as we all see the same media."

"Media do not teach stereotypes, they reinforce what already has been taught by parents, schools, churches, and the culture."

"Racist and stereotypical ideas...can be reinforced but not ordinarily introduced originally by books, movies, and/or TV."

"Where is the symbol or mascot or stereotype that determined my cousin's self-image?"

Readers respond on other stereotype issues

"I believe that bashing the 'other side' is counter-productive, a waste of time and resources."

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.