American freedom: Riding horses and shooting guns.

Phon, quoted in Cowboys and Indians, Thai-Style, 8/7/03

American freedom: Riding horses and shooting guns.

Phon, quoted in Cowboys and Indians, Thai-Style, 8/7/03

In the beginning

One probably could trace America's roots back to the dawn of civilization—or at least to the Bible. The idea of being the chosen people, of dominating less worthy humans and animals, took form there. Such Judeo-Christian beliefs became the pillar of Western civilization.

After the fall of Athens, the American ideals of liberty and equality lay dormant for almost 2,000 years. Democratic thought, anathema to medieval Christians, was punishable by death. The Black Death hastened the decline of feudalism, which led to the Renaissance and the printing press. The Reformation and the Age of Enlightenment followed.

The discovery of the Americas was obviously a breakthrough. Europeans flocked to this "uncivilized" land, with its promise of paradise. Even the "New World" label suggests its cleansing, enabling power. Here people could free themselves from the past with nothing but the limitless horizon before them.

After 1492, America's roots began to coalesce. Below are a few milestones on the road to America's present cultural values, as described in Habits of the Heart by Robert Neelly Bellah (editor), et al.

Biblical standards

Biblical religion has long been cited as an important influence in America from its earliest colonization—by Tocqueville, among others. The Puritans...although prone to viewing material property as a sign of God's approval, did have as their primary criterion for success a community in which a quality ethical and spiritual life could be lived.

Republican ideals

The republican ideal embraces the idea of a self-governing society of relative equals in which all participate....The notion of equality in this tradition does not mean that all humans are created equal in all respects, but is a fundamental political equality....The ideal was embodied in the idyllic independent farmer and cities and manufacture were feared because they would bring inequality of class and corrupt the morals of the people.

Utilitarian and expressive individualism

[Benjamin] Franklin gave classic expression to what many felt (and still feel) to be the most important thing about America: the chance for an individual to get ahead on her/his own initiative. Although he never espoused it per se, Franklin was influential in the development of utilitarian individualism in its pure form: in society where each vigorously pursues his/her own interest, the social good would automatically emerge.

Early interpretations of American culture

Hector de Crevecour—Letters from an American Farmer

His sketch of the American approximated the rational individual concerned with personal welfare, the model of Enlightenment thought—thought that was at the time receiving renewed emphasis from the writings of political economists like Adam Smith. The idea here is rational self-interested humanity—"Economic Man" so-called.

Alexis de Tocqueville—Democracy in America

He recognized the commercial/entrepreneurial spirit emphasized by de Crevecour, but found it to have ambiguous and problematic implications for the future of American freedom....Stressed here is an isolated individualism along the vein of Franklin. Tocqueville thought that this isolation to which America tended left it prone to despotism.

The independent citizen

For Tocqueville the representative character was the independent citizen—who held strongly to biblical religion; knew duties and rights of citizenship; especially a self-made "man." Representative characters are not an abstract ideals or social roles, but are realized in the lives of those who fuse their individual personality with public requirements of those roles. They are often the mainstay of myths and popular feeling, important sources of meaning for people in a particular culture.

The American character

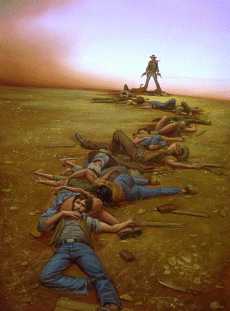

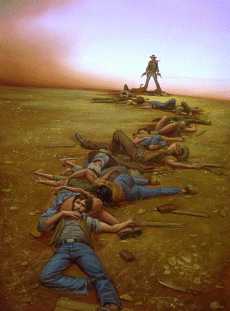

That leaves us in the first part of the 19th century with our nascent national character. In the eastern forests he was a trailblazer, pioneer, and woodsman: Natty Bummpo and Daniel Boone. But the frontier beckoned, so he saddled up and lit out for the territory. As he rode west onto the Great Plains, he morphed into General Custer, Buffalo Bill, and every cowboy ever played by John Wayne.

His mission: to tame the wilderness, to make it safe for settlement and schoolmarms. Of course that meant getting those pesky hordes of Indians and buffalo out of the way, but with his characteristic can-do optimism, it seemed only a matter of time. Once accomplished, Americans could realize their God-given right—their Manifest Destiny—to rule the continent.

The Wild West and its conquest became the central metaphor for America, and the cowboy its central hero. A hundred years of art and entertainment only solidified the cowboy's position. Painters like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell were "crucial in creating and perpetuating the myth of Western lawlessness and violence, and that the West was a place of self-discovery and freedom from social restraint," scholars say (LA Times, 7/7/01). Tom Mix, Will Rogers, Gene Autry, and Roy Rogers made the Western movie a phenomenon and were among Hollywood's biggest stars. John Wayne was voted the all-time most popular movie star; in 2000, 21 years after his death, he was still the second most popular movie star.

If the hero wasn't a singing or shooting cowboy, he was an analog in a related field. The cop, the detective, the secret agent, the soldier, the pilot, the spaceman, the adventurer, even the gangster—all were variations on the gunslinger. The American icon wasn't a kind grandfather, an enterprising merchant, a patient farmer, or—heaven forbid—a prim schoolmarm. Like John Wayne, he was the brave and bold man of few words but much action.

For an analysis of the cowboy's alleged virtues, see Cowboys Fought "Warlike" Indians and Other "Evil Men."

More on America as cowboy country

Straight shootin' with the Duke

The myth of American self-reliance

Adolf Hitler: a true American

Fact vs. fiction

Whether America's beliefs molded America's chracter or vice versa is hard to say. Perhaps fact and fiction fed on and reinforced each other. In any case, the following postings suggest how they've interacted to form America's mythology—its origin story.

From Churchill Controversy Represents a Split in America by John Mohawk. In Indian Country Today, 3/3/05:

American mythology probably dates back to James Fenimore Cooper, the "Leatherstocking Tales" and Natty Bumppo, an individual with European genes but who was raised by Indians. He possessed the best of both worlds, the supposed intelligence of the colonizers and the noble traits of the Indians, and he was a fellow who knew right from wrong and was not afraid to act.

American heroes -- mythical figures including Daniel Boone and John Wayne -- always have been like that. The mythical cowboy (there never was a historical character like him) sauntered into town, found the bad guys holed up in the saloon and absorbed their insults but came back shooting. He had no family, no roots, could ignore the rule of law when it pleased him, committed human rights violations when circumstances called for it, never made mistakes and never said he was sorry before he left town. You know the characters: Wyatt Earp, Roy Rogers, the Lone Ranger, Dirty Harry, Rambo.

After the attacks on 9/11 a lot of people in America -- the red states, to legitimize and over-generalize -- wanted America to personify their heroes, to be Rambo.

Academia is, in many ways, the antithesis to that spirit of unbounded and mindless adventurism. The culture of academia wants to know details, while Rambo has no interest in details. He never accidentally shoots the wrong people, and he's never on the wrong side because whatever side he's on is, by definition, the right side. As Rambo, America has set off a huge division within herself and has done much to psychologically isolate the United States from the rest of the world.

Academia is traditionally and rightfully skeptical of the Rambo approach -- which is part of the reason why ultra-nationalists are suspicious of academics who they feel don't know right from wrong, are insufficiently cheerful about unfounded military adventures, and spend too much time parsing nuances. The soul of the country is being torn between passion and reason, and the fact is even within academia there is plenty of passion and reason to go around.

From In Defense of Cowboy Culture by Thomas S. Engeman, 5/28/03:

Although high culture is a different story, in mainstream America, heroism is alive and well. It thrives in "action/adventure" films, by far the largest movie genre, encompassing westerns, detective and police dramas, martial arts pix, science fiction, superheroes, natural disasters, and war stories. Thousands of heroic movies (and television programs) are viewed by millions of Americans every month, though intellectuals of all stripes typically disdain them. Conservatives are more interested in high culture, great books, and great men, than in mythical appeals to the masses. And modern liberals argue that heroism encourages violence at home and militarism abroad, not to mention "fascistic" prejudices like racism, sexism, and love of force.

The huge popularity of heroic movies shows that Americans are little troubled by such intellectual criticism. They believe that calling the United States a "cowboy culture" pays it a compliment. To the average ticket-buying Joe and Jane, the cowboy (in his many forms) is the idealization of democratic virtue, especially of its relentless pursuit of justice.

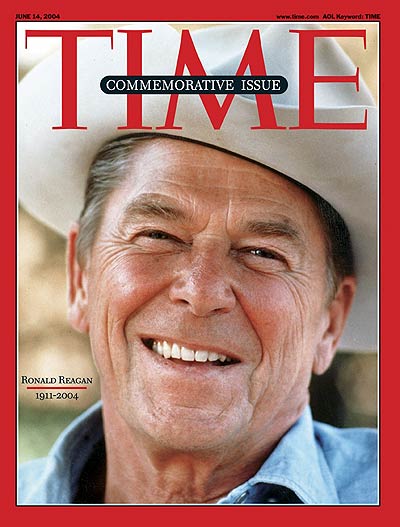

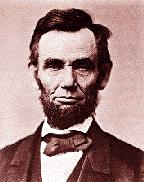

The identification of America with frontier life is longstanding in politics as well as popular culture. Presidents like Andrew Jackson, William Harrison, and Abraham Lincoln invoked their vigorous frontier origins in order to increase their democratic stature. Even after the closing of the Western frontier in the 1890's, Teddy Roosevelt cultivated his reputation as a Rough Rider in South Dakota and Cuba. A century later, Presidents Reagan and George W. Bush continue to embrace the cowboy way. The pioneer spirit has also been conjured in order to gain support for policy initiatives. Woodrow Wilson exhorted America to join World War I in order "to make the world safe for democracy"—as the pioneers had once made safe the American West. John F. Kennedy made the "New Frontier" the motto of his administration, promising to land a man on the moon within the decade. Given the supposed timidity and self-interestedness of modern democracy, what sustains this manly devotion to justice and noble achievement so long after the actual pilgrims and pioneers went to their reward?

For an analysis of the cowboy as the prototypical American hero, see Why Write About Superheroes?

More on America's self-made mythology

A shining city on a hill: what Americans believe

Manifest Destiny = America's pathology

America's exceptional values

America the warrior society

The Frontier Thesis

As the previous posting suggests, the concept of America as "cowboy country" is nothing new. In fact, one scholar forumlated a seminal theory about the role of the American West more than a century ago. As critic Mark Wibe explains:

In 1893 historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his now-famous "frontier thesis" at the Chicago World's Fair. According to Turner, "American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West. The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development." This thesis proved to be remarkably durable, and despite numerous scholarly rebuttals and counter-theses in the century that followed, Turner's interpretation of American history still enjoys the acceptance of large numbers of ordinary Americans.

Or as columnist John Balzar put it in the LA Times, 4/1/01:

Just over a century ago, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner described America's dynamic in a word.

"Westering," he called it.

Turner saw that the country was distinctly flavored, not just by the origins of its people, but by their encounters with the frontier, the land, the open space and the restless experience of migration.

Modern historians may fault the old Harvard professor and Huntington Library researcher as too Euro-white, too simplistic. But he was not wrong.

Americans cut their teeth on the frontier—both the Americans we call native and those we do not. Our mythology walks from the shadows of the forest, through box canyons of the deserts, across prairie grasses, past tumbling streams and over wind-blown summits of purple mountains majesty. These are wellsprings where we draw measures of our self-image.

Turner himself explained The Significance of the Frontier in American History. He made it clear that facing the frontier meant facing Indians. Some excerpts from his essay:

[A]t the frontier the environment is at first too strong for the man. He must accept the conditions which it furnishes, or perish, and so he fits himself into the Indian clearings and follows the Indian trails. Little by little he transforms the wilderness, but the outcome is not the old Europe....The fact is that here is a new product that is American.

The first frontier had to meet its Indian question, its question of the disposition of the public domain, of the means of intercourse with older settlements, of the extension of political organization, of religious and educational activity. And the settlement of these and similar questions for one frontier served as a guide for the next.

The effect of the Indian frontier as a consolidating agent in our history is important....This frontier stretched along the western border like a cord of union. The Indian was a common danger, demanding united action. Most celebrated of these conferences was the Albany Congress of 1754, called to treat with the Six Nations, and to consider plans of union. Even a cursory reading of the plan proposed by the congress reveals the importance of the frontier. The powers of the general council and the officers were, chiefly, the determination of peace and war with the Indians, the regulation of Indian trade, the purchase of Indian lands, and the creation and government of new settlements as a security against the Indians.

Professor Osgood, in an able article, has pointed out that the frontier-conditions prevalent in the colonies are important factors in the explanation of the American Revolution, where individual liberty was sometimes confused with absence of all effective government. The same conditions aid in explaining the difficulty of instituting a strong government in the period of the confederacy. The frontier individualism has from the beginning promoted democracy.

But the democracy born of free land, strong in selfishness and individualism, intolerant of administrative experience and education, and pressing individual liberty beyond its proper bounds, has its dangers as well as its benefits. Individualism in America has allowed a laxity in regard to governmental affairs which has rendered possible the spoils system and all the manifest evils that follow from the lack of highly developed civic spirit.

Speaking in 1835, Dr. Lyman Beecher declared: "It is equally plain that the religious and political destiny of our nation is to be decided in the West," and he pointed out that the population of the West "is assembled from all the States of the Union and from all the nations of Europe, and is rushing in like the waters of the flood...."

The works of travelers along each frontier from colonial days onward describe certain common traits, and these traits have, while softening down, still persisted as survivals in the place of their origin, even when a higher social organization succeeded. The result is that to the frontier the American intellect owes its striking characteristics. That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom—these are traits of the frontier, or traits called out elsewhere because of the existence of the frontier. Since the days when the fleet of Columbus sailed into the waters of the New World, America has been another name for opportunity, and the people of the United States have taken their tone from the incessant expansion which has not only been open but has even been forced upon them.

What the Mediterranean Sea was to the Greeks, breaking the bond of custom, offering new experiences, calling out new institutions and activities, that, and more, the ever retreating frontier has been to the United States directly, and to the nations of Europe more remotely.

Indians 'r' us

No matter which continent your ancestors came from, if you are an American, you are part Indian in your roots.

Larry Echohawk (Pawnee), address to the Democratic National Convention, 1992

Not a little of what has made the United States of America great comes from its formative consciousness rooted in the Indian's lands and peoples, in its indigenous geography. From the time of Squanto's meeting with the Pilgrims to the many encounters with Iroquois and other eastern confederacies, the new settlers, prominently including the founding grandfather Benjamin Franklin, learned to live and act and think in the American way. Truly, Uncle Sam's often reluctant but most helpful guides in that quest have been American Indian peoples.

Unavoidably, America grew strong and unique from its contact and formative inter-penetration by Indian intellect, practice, identity and example. The concept of unity of states and other sovereignties under a confederated or federated structure, the idea of privacy and individual freedom to develop and grow, the instinct and right to roam the land freely – these are all elements of American life that bear influence from a Native perspective.

"Understanding Thanksgiving: History and Prayer," Indian Country Today, 11/22/01

[Franklin and Jefferson] represented the Enlightenment frame of mind of which the American Indians seemed a practical example. Both knew firsthand the Indian way of life. Both shared with the Indian the wild, rich land out of which the Indian had grown. It was impossible that that experience should not have become woven into the debates and philosophical musings that gave the nation's founding instruments their distinctive character. In so far as the nation still bears these marks of its birth, we are all "Indians" — if not in our blood, then in the thinking that to this day shapes many of our political and social assumptions.

Bruce E. Johansen, Chapter Six: Self-Evident Truths, Forgotten Founders

As Turner suggested, the frontier question was also the Indian question. Indians were the bogeyman, the shadow in the corner of the eye, the unknown and unknowable "other." Seen through the warped lens of prejudice, the Indians were everything the Europeans weren't: wild, savage, and free. The colonists were awed and afraid at the same time.

Whether as allies or adversaries, the Indians introduced the Europeans to America. Because the natives survived without trappings the Europeans considered necessary, it spurred the newcomers into new modes of thought and action. The Europeans grew more like Indians while the Indians grew more like Europeans.

To continue the John Wayne metaphor, the American cowboy needed the American Indian to define himself, to give him purpose in life. He fought the Indian ferociously, but also learned to respect him as an opponent. The cowboy may not have realized it, but he adopted some of the Indian's beliefs and attitudes. He blended two cultural strains—the European desire for progress and control with the Native acceptance of egalitarianism and freedom—into something uniquely American.

Turner claimed the frontier broke down the Old World's class-conscious order and promoted a more robust, freewheeling, democratic society. We could just as easily credit this development to the Indian people as to the land. The Indians did more than show the colonists the Iroquois Confederacy's democratic practices. They inspired a whole new worldview.

Freedom, justice, success...these things no longer depended on where you were born, whom you knew, or what some distant king or priest commanded. A person could take charge of his own destiny, build something with the sweat of his labor, and flourish with only his kith and kin's help. He didn't need anything else.

That was the lesson of the frontier and the Indian, and it determined the American character. That explains why James Axtell wrote, "To understand the making of Anglo-America is impossible without close and sustained attention to its indigenous predecessors, allies, and nemeses." It also explains why PEACE PARTY, a multicultural comic book featuring Native Americans, isn't just about Indians. It's about us all.

Related links

Indians gave us enlightenment

Why write about Native Americans?

America's cultural mindset

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.