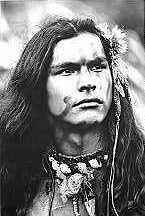

Tonto described

Of all the "Indian figures" in the history of film, the most widely known is Tonto. So, "come with me now to those thrilling days of yesteryear," as we tune in to the familiar strains of the William Tell overture, which signal that the daring and resourceful masked rider of the Plains and his faithful "Indian" companion Tonto are just one commercial away from the night's adventure.

Today, the Lone Ranger and Tonto seem mythic, ageless—part of a feudal past. In truth, they go back only to radio's pioneer days, having premiered on Detroit's WXYZ on January 30, 1933, and lasted on radio until 1954, with another 180 episodes on television, and rebirth in a couple of feature-length films.

Tonto is the very model of the screen's faithful "Indian" companion, smarter than Steppin' Fetchit and almost as clever as Charlie Chan without being inclined to spout so much ancient wisdom. Faithful companions, like other ethnic stereotypes, come in all shapes and sizes. Tonto represents the Native American as a good and noble helper, descendant of the cornbearing Red Man in grade-school Thanksgiving pageants. There are others—where would Red Ryder be without Little Beaver? Or Pa Kettle without the faithful Crowbar and Geoduck?

Rennard Strickland, Ph.D, Coyote Goes Hollywood, Native Peoples, 1/13/97

Tonto debated

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Time to Talk'um Tonto:

A correspondent recently wrote:

>> You know, if you can get past the pidgin English, the Tonto character wasn't so bad. As I remember, he was always on top of every situation, and was able to give the Lone Ranger critically good advice. It may be just my imagination (it was so long ago that I saw these flicks) but Tonto was cast as an equal to LR, not an underling. If I'm distorting this in my memory, flame away. <<

If you can get past the pidgin English?! Well, if you can get past the killing, I supposed war isn't so bad either. (A slight exaggeration, to be sure, but you get the idea.)

The pidgin English was one strike against Tonto. A second was that he had no cultural traits. He was a blank slate, a generic Indian. A third was that he was always following, always the sidekick. He had no known life outside of serving the Lone Ranger.

That robbed Tonto—and by implication other Indians—of their individuality. It subtly said that he wasn't worthy, that he was inferior—a soulless automaton that anyone could've replaced.

Heroes like Jesus or Superman have full-blown mythologies around them. Sidekicks like Tonto don't. He was the Ed McMahon or Dan Quayle of fictional Indians—a character who told us nothing except that Indians could be good.

Which wasn't exactly a stunning revelation. Uncas in The Last of the Mohicans (1826) was a much more fully-realized character. It took us a century and a half to start seeing fictional Indians deeper than Tonto.

As I recall, Tonto was generally intelligent and competent, but that doesn't mean he didn't embody several stereotypes. And let's quickly add that those were the creators' fault, not Jay Silverheels'. Silverheels undoubtedly did the best he could.

Here's a Native view of Tonto. As you can see, it's hardly benign:

Tonto was everything that the white man had always wanted the Indian to be. He was a little slower, a little dumber, had much less vocabulary, and rode a darker horse.

Somehow Tonto was always there. Like the Negro butler and the Oriental gardener. Tonto represented a silent, subservient subspecies of Anglo-Saxon whose duty was to do the bidding of the all-wise white hero.

Vine Deloria Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux), Custer Died for Your Sins

The "good" Indian

In his book Lies Across America, James W. Loewen discusses Tonto's role in our cultural dialogue. Even if Tonto were a perfectly realized Indian, he would convey a meta-message about American history. As Loewen explains it:

To soften invasion narratives, conquerors often highlighted the stories of natives who helped them. Americans might call these "Tonto figures" after the Lone Ranger's famous sidekick—the archetypal "good Indian," always ready to help track down the "bad Indians" and outlaws who menaced whites on the frontier.

Our national culture particularly heroifies the first two "good Indians," Pocahontas in Virginia and Squanto in Massachusetts, who became famous foundation figures in our origin myths. Some newcomers inherit directly through Pocahontas, who married John Rolfe and had many descendants. Squanto had no European progeny, but his friendship and assistance led to the first Thanksgiving, our national origin banquet. As translator, ambassador, and technical advisor, Squanto was essential to the survival of Plymouth in its first two years. William Bradford called Squanto "a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation." Not only were Squanto and Massasoit [another "good Indian"] on the European Americans' side; so by implication to men like Bradford was God.

Tonto figures still play an important ideological role in explaining and excusing the elimination of Native peoples. When European Americans honor "good Indians" by putting up their statues or marking their homes, they are trying to define themselves as "good white people." Whites deserve the country, goes the implicit argument. Look—here are the good Indians who welcomed us to it and helped us take it.

The Straight Dope echoes this point with regard to Sacagawea:

After the Indian wars, Sacagawea and other "good Indians" ironically became symbols of the rightness of manifest destiny and white displacement of the Indians. Here was an enlightened Indian maiden, the thinking seems to have been, who recognized the superiority of the white race and the inevitability of subduing the west. That this unusually perceptive Indian helped achieve that goal just goes to show that the conquest of the west was best for the Indians too, even if they didn't know it yet. This racist line of thinking is no longer emphasized, but it did play a part in the late nineteenth to early twentieth century lionization of "good Indians" like Sacagawea, Pocahontas, Squanto, and Massasoit.

Loewen has written about America's historical monuments, statues, and markers, but the same applies to all our myth-making apparatus. It especially applies to the stories we tell—on TV and in movies, in books, and in comics. The Lone Ranger and Tonto, other Western shows, and movies such as Pocahontas and The Road to El Dorado are all good examples.

Other "good Indians" from fact and fiction include Friday, Chingachgook and Uncas, Mingo (from Daniel Boone), and the Lakota in Dances with Wolves. Many Indians have earned praise in our history books by helping the Euro-American colonizers conquer their neighbors' land, or their own. Even if these Indians had separate identities, their fame comes from helping the white man, not helping themselves.

Therefore, it's not surprising Hollywood has lavished the biggest budgets on Pocahontas and Last of the Mohicans while relegating "contrary" figures like Geronimo and Crazy Horse to minor movies or cable TV. A more correct version of The Lone Ranger is possible, but not a movie in which Tonto is the star. Our entertainment machine doesn't want to—perhaps can't—mythologize heroes who don't pursue the American Dream.

Related links

The Lone Ranger

TV shows featuring Indians

The best Indian movies

Readers respond

"Movies and TV are mostly lowest common denominator 'entertainment' and really ought to be beneath criticism other than to observe that dreck is dreck."

"Colonial Americans got caught up in neolithic Native American conflicts that had been going on for eons."

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.