An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay The Feel-Good National Museum:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay The Feel-Good National Museum: An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay The Feel-Good National Museum:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay The Feel-Good National Museum:

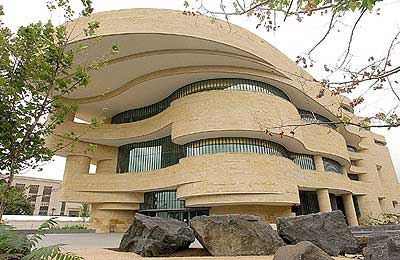

The debut of the National Museum of the American Indian was probably the Native story of the year in 2004. When the NMAI opened in September, every newspaper seemed to have something to say about it. Indians had finally taken their rightful place among the icons of the National Mall, they declared.

Because a Native museum presents art and artifacts to a general audience, it exemplifies "the intersection of popular culture and Indian Country," the subject of this newsletter. Let's see what people thought about this groundbreaking tribute to Native life and lore.

"The circle is complete"

The good...

From the LA Times:

The capital salutes its first nations

America's native peoples finally have a tribute to their culture at a new Smithsonian museum.

By Johanna Neuman

Times Staff Writer

Sep 18 2004

WASHINGTON — Conch shells will blow from the balcony of the Smithsonian's Castle. A procession of 15,000 people, many in native regalia, will march toward the U.S. Capitol amid an extravaganza of drumming, singing and eagle feathers. Four times marchers will pause to honor cultures from each of the cardinal directions — north, south, east and west.

On Tuesday, Washington welcomes perhaps the most unusual addition to its museum scene since 19th century British scientist James Smithson bequeathed his estate for "an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men." Many museums later, on the last plot of land on the nation's Mall, the National Museum of the American Indian opens its doors to huge cultural expectations.

"In the profoundest possible sense, this institution speaks to all of us about cultural memory, remembrance and future," said museum director W. Richard West Jr., a Stanford-educated lawyer and a Southern Cheyenne.

Noting the "long and often troubled past relationship between peoples," West told the National Press Club last week that the museum is "a powerful metaphor for a seminal convergence of the histories of this hemisphere that has the potential to alter forever … the cultural consciousness of the Americas."

In other words, reconciliation of two histories — European and American Indian — under one roof.

Everything about the museum — whether the Kasota limestone imported from Minnesota to suggest a building carved over time by wind and water, or the Mitsitam ("let's eat" in the Piscataway and Delaware languages) Cafe that will serve meals based on indigenous foods, such as buffalo meat and roasted corn — echoes the theme.

The museum opening begins a six-day celebration of dance, music and storytelling that planners are calling the First Americans Festival — and they take special pride in the irony of being the last on the Mall.

"We are the last to be built on the Mall, but the irony is we were the first on the hemisphere," said Jim Pepper Henry, the museum's assistant director for community services and a member of the Kaw Nation of Oklahoma and the Muscogee Creek Nation of Oklahoma. "This is a dream for a lot of native peoples. We're not here just to focus on the past and celebrate native culture. This is also, as our director said, about reconciliation."

Ironies abound.

Across the street from the popular Air and Space Museum, the new Indian museum is designed to preserve and honor native cultures that were threatened by an expansionist United States.

And now it sits within sight of the U.S. Capitol, as West put it, "the very head of the national capital's monumental core."

With its curving, flowing architecture, the museum is in striking contrast to the linear marble of nearby Neoclassical government buildings. A 12-minute orientation film, "Who We Are," showcases the diversity of Native American communities — nearly 3 million people in the United States, according to the U.S. census — without dwelling on the wars with white settlers that jeopardized the Indian way of life. A "Wall of Gold" exhibits gold objects owned by native people before they were coveted by Europeans, to illustrate the wealth once held. Landscaping on the 4.25-acre site includes plant life that existed before the conflict with the Europeans, including more than 40 large "grandfather rocks" that, explained Duane Blue Spruce, an architect on staff, speak to the longevity of the Indian people. And the museum faces east, to greet the rising sun, an important ritual to people who were pushed west by conquerors.

The museum was approved by Congress in 1989, the same year the Smithsonian took over George Gustav Heye's collection in New York. An investment banker who amassed one of the world's largest collections of Indian artifacts — including Sitting Bull's war bonnet and a collection of scalps — Heye left objects that date back more than 10,000 years and form the heart of the new collection. The Smithsonian umbrella covers not only the new museum and the George Gustav Heye Center, a permanent museum in Lower Manhattan, but also the Cultural Resources Center, a research and collections facility in Suitland, Md.

Almost 90% of the new museum's holdings comes from Heye, who collected from native communities in the first half of the 20th century. Because some of his acquisitions were less than scrupulous, the museum has placed "our highest priority" on repatriation of human remains, such as war-trophy scalps and bones, said Pepper Henry.

A full-time staff of four is charged with researching the collections to see if human remains, sacred and ceremonial objects or other important cultural artifacts should be returned. Pepper Henry said that since the museum staff first began working in 1990, more than 2,000 objects have been returned to 100 native communities throughout the hemisphere.

From the beginning, museum planners sought to avoid the conventional approach to interpreting native cultures by what West called "third-party viewpoints," often academics with few personal ties to their subjects. So they reached out to 24 tribal communities in the United States, Canada and Latin America. In two dozen consultations in the early 1990s, they crafted a template that would define the museum's themes. Planners wanted a validation of history but also a recognition of vibrancy.

"Visitors will leave this museum experience knowing that Indians are not part of history," West said in announcing the six-day festival on the Mall. "We are still here and making vital contributions to contemporary American culture and art."

Thus, exhibitions include ancient artifacts, such as a 2,000-year-old ceramic jaguar clutching a man between its paws, as well as works from 20th century Indian artists George Morrison and Allan Houser. A skylight reflects sunlight onto a central gathering place — this one a 120-foot-high atrium. A welcome wall greets visitors in 200 native languages — this one on a high-tech photomontage. At the Lelawi Theater (the name means "in the middle"), digital film screens are made to resemble Indian blankets. Even the two craft shops — the Chesapeake ("shell of greater value") and the Roanoke ("shell of lesser value") — showcase both traditional artwork and modern merchandise.

The museum is not without its detractors. The original architect, Canadian Douglas Cardinal, who has roots in the Blackfeet and Ojibwa communities, was fired by the Smithsonian for missing "contractual performance requirements" and is threatening to boycott the opening ceremony, calling the building "a forgery." Some scholars worry privately that a museum devoted to serving tribes may be too politically correct to be historically edifying.

But museum planners are proud of their choices — "We are guided by a set of ideas," said curator Gerald McMaster, a Cree artist.

"The selection of objects begin to illustrate the ideas, rather than the other way around." — and predict 4 million visitors a year to a museum that cost $199 million to build.

Besides, the food is already drawing raves.

"It was awesome, the most unique menu on the Mall," said Pepper Henry, after lunch at the cafe's debut Sept. 10. Asked if he worried that vegetarians might find buffalo meat a concern, he said, "American Indians have been eating buffalo for hundreds of years. It's healthy, low-fat, high in protein and very tasty. Why should we stop now?"

Copyright 2004 Los Angeles Times

From conquest to casinos in eyes of Indians

New museum shows vitality of cultures

Edward Epstein, Chronicle Washington Bureau

Sunday, September 26, 2004

San Francisco Chronicle

Washington — If the new National Museum of the American Indian confined itself to such displays as its impressive collections of Seminole, Shoshone and Hopi kachina dolls, or North American peace pipes and tomahawks, it would differ little from other major museums that tend to treat Indian culture as anthropological history, a relic of the past.

Instead, the Smithsonian Institution's 18th and newest museum — which opened Tuesday on the last major parcel of land on the 200-acre National Mall — is very much a place of a living, varied culture.

Indians from throughout the Western Hemisphere were deeply involved in curating the exhibits and even in shaping the 250,000-square foot building, whose curved shape, 120-foot-tall atrium and limestone exterior have drawn raves from architecture critics.

The result is very much a living museum, a place that immerses visitors in today's Indian culture and isn't afraid to show Native Americans' deep sense of grievance, even anger, over how they have fared in the 500 years since they first disastrously encountered European civilization.

That focus is apparent from the moment the visitor enters "Our Peoples," the first of four main galleries in the museum. The tone is set immediately, asking visitors to think of Indian life in 1491, one year before Christopher Columbus showed up. "They aren't Indians. They have never heard of America," a panel says, pointing out that before the first encounter with Europe there were tens of millions of Native Americans, stretching from southern Chile to the Arctic Circle.

Eventually 95 percent of that native population would vanish from disease and war, said curator Bruce Bernstein. "We bring together disease and colonization because disease went hand in hand with colonization," he said, standing not far from an exhibit put together by the Seminoles of Florida, who note defiantly that they are the only major tribe in the United States that never signed a peace treaty with the federal government.

"That's why we're 'The Unconquered,' " the tribe says in its presentation about its history and its current lifestyle that is centered on raising cattle and tourism.

Nearby is the exhibit space of the Kiowa Nation of Oklahoma, who are among 24 of the thousands of separate Indian tribes, bands and groups from across the hemisphere chosen for the museum's first round of exhibits, which will be taken down in about two years and sent to tour the country.

The blown-up words of one of the Kiowas interviewed for the museum, Arvo Mikkanen, tells why Indians view white man's culture with such deeply mixed feelings. "When the chiefs agreed to the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek (in 1867) they reminded the government not to forget its promise.

"Well, Kiowa fears were realized. The United States broke up tribal lands, sold them and surrounded us with people who didn't believe in our tribal culture, religion, ceremonies or language," Mikkanen said.

Many of the 8,000 items on display in the museum come from the collection of George Gustave Heye (pronounced like "high"), a wealthy New York City businessman of a century ago who became a compulsive collector of Indian artifacts, eventually amassing about 800,000 items.

But the Smithsonian, as a federal institution, has access to such other repositories of Indian history as the National Archives. That's where Bernstein says the museum found one of its most moving pieces, a 100-foot-long piece of glued-together paper carrying the signatures and personal marks of thousands of southeastern Cherokees petitioning President Andrew Jackson to let them stay on their native lands, rather than be forcibly moved to the West.

The petition failed, of course. Most of the Cherokee ended up in what is today Oklahoma. Only a remnant of the tribe called the Eastern Band of Cherokees remains on ancestral lands in North Carolina, where they have finally found some economic well-being by owning a casino operated by Harrah's.

The first two California tribes on exhibit are the Hupas of Humboldt County, whose display centers on ceremonial dances that are key to their spiritual life, and the 3,000-member Campo Band of Kumeyaay Indians who live on a 16,000-acre reservation southeast of San Diego along the Mexican border.

The Campo exhibit includes a small section on one of the most revolutionary, if controversial, developments in Indian life. The tribe is one of dozens across America that now own a casino — in the Campo's case the Golden Acorn Casino along Interstate 8.

The band's description of the casino shows that Indians feel legalized gambling has at last given them a leg up in the world.

"Just as the acorn once served as the staple of the Kumeyaay diet, the casino is viewed as mainstay of our economy and a symbol of economic independence," the band says in its script for visitors.

Perhaps the most amazing thing about the museum's Indian-centric view of things is that the building is just several hundred feet from the U.S. Capitol and occupies the slice of the mall nearest to the Capitol. In fact, the main entrance of the museum, which received $119 million in appropriations from Congress, faces the Capitol, as if to say the Indians are still here, are a vibrant part of America and plan on being around forever.

"We're trying to represent native peoples' lives' journeys," said another curator, Emil Her Many Horses, a member of South Dakota's Oglala Lakota Nation. "It's what they want to show. Their main message is that they're still here."

The museum embodies the Indian view of the world and nature, even in its flowing design that avoids sharp corners, as a recognition of the native view that buildings should blur distinctions between the indoors and the outside. All the walls curve, and the ceilings in the main 320-seat auditorium and in the "Our Universe" exhibit are blue and full of pinholes, representing the night sky.

Even the museum restaurant, called Mitsitam ("Let's eat" in the Lenape language) veers far away from the burger and fries menus of most museums. There is a burger, for $4.95, but it's a buffalo burger. And there's also Quahog clam chowder, cedar planked juniper salmon and pueblo tortilla soup in the long menu, selected to represent five regions and prepared where possible with ingredients supplied by Native American vendors.

Museum officials say they expect at least 4 million visitors a year, which in Smithsonian terms isn't such a vast number. The museum's immediate neighbor to the west, the National Air and Space Museum — the most visited of the Smithsonian's outposts — had 9,389,646 visitors in 2003. The Indian museum isn't as big, however, so it has adopted a system requiring timed passes for admission, just like the busy U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum about a mile away.

Another exhibit panel introduces visitors to the term "survivance," a word that offers an apt definition of the new museum's view of its own mission: "Survivance is more than just survival. Survivance means doing what you can to keep your culture alive."

By Michael Kilian

Tribune staff reporter

Published September 26, 2004

WASHINGTON — The National Museum of the American Indian—which opened Sept. 21 as the Smithsonian Institution's newest and easily most extraordinary cultural facility—was created largely to convey two messages.

One is that, after centuries of conflict with the white man's civilization and the destructive forces of modern times, the native peoples of the Western Hemisphere have somehow managed to survive with their rich and diverse cultures intact.

The other is that the time has at long last come for the people of the United States, who heretofore have viewed Indians in stereotypical terms ranging from bloodthirsty savage to noble environmentalist, to truly understand who the native peoples are and why they hold their cultures so dear.

The museum is the last to be erected on the capital's National Mall and is expected to draw crowds rivaling those of its popular neighbors, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and National Museum of Natural History.

It is as genuinely Indian as any such institution could imaginably get. The museum director, W. Richard West, is a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, and fully 30 percent of the museum staff is of Indian descent. Tribal representatives from all over the country and the Western Hemisphere were consulted about all aspects of the museum's design and content.

This is far from just another dull, square building filled with dull collections of artifacts in glass cases. Indian civilization is represented by infinitely more here than pottery, blankets and headdresses, as has often been the case with other venues.

Visitors will come away from their experience here with a sense of winds howling through Southwestern canyons and over frozen Arctic wastes, the brightness and importance of the moon as a regulator of lives, the worship of water and corn as life forces, and the spiritual oneness of humanity with nature.

They will learn that the term "American Indian" embraces a vast complex of individual cultures and "universes" involving no fewer than 150 different languages and extending geographically from Alaska to the Straits of Magellan.

They will see amazing art, such as the contemporary sculptures of Apache artist Allan Houser, and learn of Indian migrations to big cities such as Chicago, Pittsburgh and New York, where many practiced the daring calling of ironworker in the construction of some of our most monumental buildings.

They will hear a tribal leader talk about how his ancestors used to travel to the federal government in Washington bearing wampum and peacepipes, adding, "Now I go with a briefcase and a couple of lawyers."

The museum building itself, located just east of the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum, is worth a visit simply for its stunning architecture and landscaping.

Created by a design team led by Blackfoot Indian architect Douglas Cardinal of Canada, the five-story-high, 250,000-square-foot limestone structure has the hue of a sandy, rocky mesa and a striated, curving surface with numerous indentations and overhangs that give it the aspect of something carved by wind and water over centuries in the American Southwest.

The surrounding grounds on its 4.25-acre site have plantings of 30,000 trees, shrubs and plants representing 150 different species indigenous to present or former Indian habitations.

A small watercourse replicating the capital's Tiber Creek (since paved over by Constitution Avenue) and a 6,000-square-foot wetlands, with lily ponds, wild flowers and wild rice, adjoin the museum's entrance, which faces east to greet the rising morning sun.

Fifteen years in the making, the museum cost $199 million, much of it raised through contributions from some 277,000 individual donors.

Entering the building, one comes upon its most striking feature—a 120-foot-high, 100-foot in diameter atrium called the "Potomac," after the Algonquin/Powhatan word meaning "where the goods are brought in."

Functioning as a meeting place and a stage for performances and cultural programs, the Potomac is partially bordered by semi-circular fencing, as one might find at an Indian village at ground level. Wall facings are of a variety of materials, some designed to react visually with sunlight focused through glass prisms set high in a window on the south wall.

One proceeds next via elevator to the fourth floor and the Lelawi Theater and its continuously showing 13-minute film, "Who We Are."

Though it embraces thousands of years of Indian civilizations, the NMAI is fully a 21st Century museum of the future, employing all manner of advanced technologies to make its presentations lively and compelling.

This is particularly true of the multi-media Lelawi and its emotionally moving film presentation. A circular chamber with seating around the periphery, it features a central formation from which hang white Indian blankets that serve as screens and large rocks on which are projected colored lights and replications of flame.

The large circular ceiling of the Lelawi is a separate movie screen, displaying 360-degree views of forests, canyon walls, rushing streams, public places like Mexico City's Zocalo, and other wilderness and urban landscapes as accompaniment to the main subject on the smaller screens.

The film is breathtaking, both in picture and in word. "We know where we are from," says one tribal member as the sky overhead blows dark and cold and flames play on the rocks below. "We know who we are."

Adjoining the theater is a complex, curving series of displays of Indian "Universes," each devoted to the life, culture, philosophy and surroundings of eight Indian communities, including New Mexico's Santa Clara Pueblo, Canada's Anishinaabe tribe and the Lakota of South Dakota.

A member of one northern tribe explains: "We are made up of two major classes—summer and winter people. Everyone belongs to one of these two groups. But there is no dividing. There is just a sense. Because all of us, whether we are winter or summer people, are seeking a good life."

Another exhibition dwells on the importance of gold to Indians in the Western Hemisphere, both as ornamental art and as an attraction for Christopher Columbus and other European explorers, conquerors and colonists who destroyed so much of Indian life.

Another section, "Window on Collections: Many Hands, Many Voices," shows the diversity of Indian art and crafts with some 3,000 objects on both the fourth and third floors. In it one finds a spotted Hopi katsina doll, a pair of beaded sneakers and an Eskimo rendition of the Statue of Liberty made of sea lion intestine, sea lion hide, fur, wood and blue marbles.

Descending to the third level by means of the museum's huge, curving central staircase, one encounters "Our Lives: Contemporary Life and Identities."

This introduces us to a multiplicity of Indians in modern times who have survived as a people from the days of Columbus and the Massacre at Wounded Knee. They have become citizens of the world while retaining strong ties to their past.

As Paul Chaat Smith of the Commanche tribe notes in introductory wall text, "Just as they did in 1491, Native Americans today live in a land that is ancient and modern, diverse and always changing. They number in the tens of millions and live in the hemisphere's most remote places and its biggest cities. They fly spacecraft and herd llamas, write software and grow orchids, fight wars and teach chemistry. They trade stocks from Park Avenue apartments, drive taxis through Lima's rush hour and sell shoes in Kentucky strip malls. Modern American Indians are not shadows of their ancestors, but their equals."

One display here, designed to look like Chicago's American Indian Center, explains the phenomenon of Indian migration to that and other cities during much of the 20th Century.

This is a museum devoted to culture, not history. There is a long display case on the third floor containing a vast array of firearms used by and against Indians in some three centuries of running battle, but little else dealing with warfare, which was an important part of Indian life and history.

Like the fierce Vikings, Huns, Goths and other counterparts in Europe, Indians were indeed "savages" in their manner of warfare—especially in the way they waged it against rival tribes. The memoirs of early French explorer Antonie de Cadillac attest to the atrocities practiced routinely against Indians by other Indians. Both sides in the French and Indian War and the American Revolution used Indian allies as terror weapons against civilian populations.

But the nobility of the native peoples and their love of nature is unquestionable. Perhaps an exhibit might have been de-voted to these contrasting aspects of their civilizations—as well as to the late 19th Century policies of the U.S. government that at times amounted to genocide.

In the meantime, the temporary exhibitions in the museum's third floor galleries are of art—the extraordinary, wind-smooth sculptures of the Apaches' Allan Houser (originally Haozous,1914-1994) and the paintings and woodblock art of Chippewa George Morrison (1919-2000).

Much loved in the Western art capital of Santa Fe, Houser produced such masterpieces as "Morning Prayer" and "Reverie," on view here with Morrison's largely abstract works through the fall of 2005.

Also on the third floor is a fully computerized resources center for researchers and scholars.

The museum's second floor is taken up mostly by the upper level of its more orthodox Signature Film Theater and the main museum store, whose goods include clothing and excellent blankets, as well as recordings of Indian music and craft items.

In addition to the Potomac atrium, the ground floor contains the main floor of the Signature Theater, a second gift shop specializing more in art objects and books, and the museum's unusual if somewhat expensive Mitsitam Cafe, named for the Piscataway and Delaware word for "Let's eat."

This restaurant, which manages to look both sleekly modern and yet in complete harmony with the building's timeless motif and natural materials, is unique in that only Indian or Indian-style foods are served.

But these include juniper salmon, chicken tamales, pumpkin soup, quahog clam chowder and a cheeseburger made with Buffalo meat.

Copyright © 2004, Chicago Tribune

Tribes Welcome 'Long Overdue' Tribute

Native Americans March to Museum of Their Lives

By Paul Schwartzman

Washington Post Staff Writer

Wednesday, September 22, 2004; Page A01

Thousands of Native Americans, many in full tribal regalia, converged on the Mall yesterday to celebrate the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian, a colorful, emotional and triumphant milestone in their long-standing quest for national recognition.

In fringed ceremonial dresses, skirts jingling with ornamentation and headdresses that told the stories of their people, representatives of more than 400 tribes formed a procession that started at the Smithsonian Castle. For more than two hours, they filed up both sides of the Mall before ending at the site of the dedication near the foot of the Capitol.

"To all our Native American friends here today, I say: 'The sacred hoop has been restored. The circle is complete,' " Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell (R-Colo.), a member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe in headdress and buckskin jacket, told the crowd. "The reemergence of the native people has come true."

On a cloudless, sun-splashed day, the dedication and procession were the focal points of an event that organizers said drew 55,000 spectators, in addition to 25,000 Native Americans, to the Mall. The festivities included the opening of the museum to the general public, the beginning of a six-day First Americans Festival on the Mall between Third and Seventh streets NW and an evening concert featuring Native American performers.

But the emotional high point was the procession, which brought together tribes and native communities from across the Western Hemisphere — everyone from the Chickaloon Native Village of Alaska to the San Carlos Apache tribe of Arizona to the Tapirape of Brazil — in a dazzling display of elaborate, colorful native costumes and a cacophony of drums.

After a Hawaiian musician on the balcony of the Smithsonian Castle blew a conch shell horn at 9:30 a.m., the procession moved along the Mall toward the morning sun, past crowds of spectators that stood as many as 10 deep in some places.

Over and over, tribal members said it was the largest native gathering in which they had participated. And the significance, they said, was only magnified by the geography, on the same hallowed terrain as the Washington Monument and memorials saluting everyone from Abraham Lincoln to veterans of World War II and Vietnam.

"This is the greatest thing to happen to Indian people in 500 years," said Nate Mayfield, 60, a Cherokee chiropractor from Colorado, wearing a deerskin shirt and pants and moccasins. "Since the beginning, we have been shoved around and killed and shut out, and this is a symbol of our survival."

Harlan Bearhand, 51, a member of the Arizona-based Gila River Indian community, said it was difficult not to think about the atrocities that Indians have suffered over the past five centuries.

"This was our land, and they came and took it without asking," he said after arriving at the Mall carrying a suitcase packed with the buckskin shirt and loincloth that he planned to wear. "They slaughtered a lot of people who didn't need to be slaughtered."

But, he said: "That was yesterday. I have to look forward to tomorrow. They have finally allowed the American Indian to be part of the history of this country."

Bearhand said he eagerly anticipated visiting the $219 million museum, a curving, sand-colored edifice designed to resemble a windswept southwestern rock formation. When the dedication ceremony ended, a stream of visitors headed for its entrance.

Mariah Cuch, 28, a Ute from Fort Duchesne, Utah, was among the earliest visitors, peering over the edge of a walkway on the fourth floor and staring at the flow of tourists, Native Americans and Smithsonian staff members below.

From her spot, Cuch had a breathtaking top-down view of the 120-foot-high atrium called the Potomac. Surrounding her were the white spiraling stairwells of the museum, and down below was the Potomac's wide wooden circle, in the center a disk of red granite.

"It's very humbling," said Cuch, in a blue-toned beaded buckskin dress. She wore a beret of beads in the shape of a hummingbird on one side of her head and white eagle feathers in her hair.

As she spoke, she turned her back to a jewelry exhibit to take in the view of the people streaming in. "Life and culture is not about an object or even a building," she said. "It's about the people. . . . You can stand here and look at the movement of people and it's like blood. . . . The blood coming into it, and bringing it alive."

Just after sunrise, tribal representatives had started lining up for the ceremonial procession, assembling outside the Smithsonian Castle, where sprawling white tents were erected for men and women to change into ceremonial garb.

Daphine Strickland, 59, a member of the North Carolina-based Lumbee Tuscarora tribe, rested on a park bench with two friends as she waited. She said she left her husband at home and drove all night to participate.

"I wouldn't have missed this for anything," she said, wearing a beaded headband and a cotton and velvet ceremonial dress. "This represents a healing, a coming together. We have survived a holocaust in the Americas, and the story has not been told. This is the beginning of telling that story."

Following the conch horn blast, Campbell and Smithsonian Secretary Lawrence Small led the procession toward the Capitol, while clusters of journalists — some from as far away as Russia — jostled to keep up.

Sprawling crowds of spectators lined the route, many shooting videotape and snapping away with disposable cameras.

"Hello to you," a spectator called from Jefferson Drive as Carol Parra, 44, of the Arizona-based Gila River community passed with a dozen or so members of her tribe.

"Top of the morning!" another man called out.

Parra smiled. "It's wonderful to see so many people who are happy to see us," she said. "What a cool feeling."

The sentiment seemed to be shared by the spectators, many of them non-Native Americans who took off the morning from work or school to watch. Officials reported no traffic or Metro problems, despite the closing of several thoroughfares. Metro ridership was heavier than usual.

"When are you ever going to see something like this again?" asked Susan Magee, 59, of Adams Morgan, a hypnotherapist and retired federal policy analyst, as she stood near Jefferson Drive.

Small presided over the dedication ceremony, which began with the Hopi honor guard performing a tribute for Pvt. Lori A. Piestewa, a member of the Hopi nation who was killed in Iraq, the first Native American woman to die in an overseas battle for the United States.

Speakers included Sen. Daniel K. Inouye (D-Hawaii), who with Campbell sponsored the 1989 legislation passed by Congress that mandated the museum's construction. It is the Smithsonian's 18th museum and the first on the Mall since 1987.

Inouye told the crowd that nearly two decades ago he made a discovery about the nation's capital that inspired him to propose the creation of a museum.

"I couldn't believe that out of 400 statues and monuments, there was not one for the Native American," he said. "This monument to the first American is long overdue."

Alejandro Toledo, president of Peru, and W. Richard West Jr., the museum's director and a member of the Southern Cheyenne tribe, also addressed the crowd. President Bush sent greetings that were delivered by Rep. Tom Cole (R-Okla.), a member of the Chicasaw nation.

Then the festival began, as crowds watched performances by singers and storytellers and lined up at food concession stands selling everything from Indian tacos to sweet potato fries.

In a tent devoted to craftsmen making musical instruments, Rock Pipestem, 32, a member of the Norman, Okla-based Otoe-Missouria/Osage tribe, started on a 15-inch high drum as a small crowd formed around his booth.

A drum can take as long as three weeks to make, but Pipestem said he could complete it by tomorrow, particularly with so much unaccustomed attention.

"This is giving me an adrenaline rush," he said. "I'm going to get this baby done."

From the dedication, the crowds streamed toward the museum's entrance, where a line of people had formed. The museum remained open overnight and will not close until 5:30 p.m. today.

But some had made sure they wouldn't have to stand in an overnight line. Lance Kimmel, a lawyer from Los Angeles, was among those at the front, clutching VIP passes he had obtained for having made a $500 contribution to the museum.

"We got our tickets eight months ago," he said. "We've been waiting a long time."

Standing just inside the entrance, Glynn Crooks, 53, vice chairman of the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux community of Prior Lake, Minn., leaned his head back to gaze up toward the top of the 120-foot atrium.

"Awesome," he said before wandering off to see the exhibits.

Staff writers Steve Ginsberg and Lyndsey Layton contributed to this report.

Sunday, September 26, 2004

Indian museum is alive — and working toward a brighter future

MARK TRAHANT

SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER COLUMNIST

WASHINGTON — I saw the sun come up over the Capitol the other day. It was the last day of summer, ideal weather, the kind of day some used to call "Indian summer." A friend of mine even spotted a pair of eagles flying over the Washington Mall.

This is a season finale, of sorts. But it's a different kind of equinox, marked by the grand opening of the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian on the mall.

Thousands of Native Americans, representing some 400 tribes from North and South America, traveled to Washington for this festive beginning.

"Today, Native American tribes take their rightful place on the national mall in the shadow of the Capitol building itself," said Richard West, the museum's director and a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes of Oklahoma.

"History seems to stand still, silent in honor," West said, calling the hope for the museum "four centuries in the making."

Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell, R-Colo., a sponsor of the original legislation, said the museum is symbolic of an American Indian re-emergence. "The sacred hoop has been restored, the circle is complete," said Nighthorse, a Northern Cheyenne.

The president of Peru, Alejandro Toledo, said the understanding of indigenous people and issues is critical to the understanding of the Americas. Toledo is Andean, the first elected native leader in the hemisphere. He said cultural respect is an essential element for national stability, democracy and freedom.

At their best, museums tell stories. They show an artifact, a piece of jewelry or photograph. Those images, items and people are frozen in time. They represent a past, perhaps something forgotten. But the challenge of an American Indian museum is to do more. It must change the story, not just reflect the past.

Sen. Daniel Inouye, D-Hawaii, said he first understood the importance of the native story when he read about the Smithsonian's collection of some 18,000 Native American skulls and other human remains. "I went to see it for myself," he recalled. "There in neatly arranged green boxes were the remains." These remains were collected on battlefields or from desecrated graves.

"How would Irish Americans or Japanese Americans react if their ancestors were in green boxes?" Inouye asked. "Long after the Indian wars, Indian people were still arranged in green boxes."

But the warehouse of human remains fit America's national mythology in one way because the story so often told identified the American Indian as an "obstacle" to progress. Some tribal people were removed to distant lands. Others were killed in such great numbers that their very presence in a particular place was erased.

The news media told this story often. One 19th-century Northwest newspaper editorial called for a treaty council, followed by a grand feast. "Then just before the big feast, put strychnine in their meat and poison to the death the last mother's son of them," the newspaper said.

A less lethal version of this story was the directive from many government or mission-run boarding schools to "save the child," by killing the Indian.

The story of conquest — or the American Indian as an obstacle — was told alongside the story of the noble savage. This story has its roots in popular fiction of the 19th century. But versions of this story have been amplified by Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West show, television and movies. The Wild West show retold Cody's fanciful accounts of a pristine native world destroyed.

The significance of the National Museum of the American Indian is that it challenges these worn-out narratives. American Indians are not forgotten, displaced or dead. The people are here. There is a future for Indian Country — and it's a path that's woven into the stories about the future of the United States.

The name "National Museum of the American Indian" is almost a misnomer in that sense.

The stories are from the Americas, not just the United States. The stories are plural, reflecting a diversity of cultures from the Arctic shores to the tip of South America. The stories will be specific, told by the very people that most museums purport to represent.

In that sense, Washington is the ideal spot for such a museum. Since its first days as a capital city, American Indian leaders have been going back and forth to conduct business.

I remember my grandmother showing me a picture when I was a child. It was a photograph of father, wearing a stylish suit. The U.S. Capitol was in the background. The year was 1908.

My grandmother showed the picture — and told the story of how her father, an Assiniboine tribal leader, viewed Washington and how tribes needed to succeed there for their people back home.

The museum story of American Indians should be told in a future tense, not just a frozen past.

NMAI director West put it this way at the grand opening when he said we must insist that Native American culture "is alive" and the museum will "use the voices of Native people themselves in telling that story."

That insistence, he said, goes beyond Native America, because the first Americans are a part of the "cultural future of America."

The future narrative of Native America is the most important role for the new museum. But the museum's opening already missed one part of that story. The entire grand opening platform presentation was about the role of men in starting the new museum (with the exception of a woman who chaired a board that donated a huge collection).

Indian Country's past, present and future needs to include the extraordinary contributions of American Indian women. The first staged story of NMAI did not do this: It was a story told by and about senators, big donors and other powerful players. But the efforts of many — especially women working in staff jobs or with intertribal organizations — made this museum happen, too. Even the design of the museum, including the habitat and crops, invokes images of a home.

Suzan Shown Harjo, a citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribe of Oklahoma, along with George Horse Capture, a member of the Gros Ventre Tribe of Montana, opened the public doors to the museum for the first time after the ceremony.

"This is the way it should be," Harjo said, a balance between male and female.

Earlier in the day, she said, she saw a pair of eagles flying over the mall, male and female. "That was the right way."

That is the right way to open a museum — and more important, it's the right way to shift the narrative going forward. This is a new story for the country, a story of hope, of complexity, and of the future. It's also a story of less conflict, success and a shared journey. This is an Americas story — and an Indian summer story.

Posted on Sun, Sep. 26, 2004

The National Museum of the American Indian: An overdue honor

By Mary Annette Pember

WASHINGTON -- On Sept. 22, virtually every daily newspaper in the United States ran a photo or a story about the previous day's opening of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington.

As I read about the opening events, procession and celebrations, I realized that for the first time in my 40-plus years I've seen Indian people being featured prominently in the news not in relation to substance abuse, poverty or crime, but rather as vital members of this country.

As an Indian woman, this fact alone makes this a day for me to celebrate.

More than 25,000 American Indians representing more than 400 tribes participated in the procession along the National Mall. Some dressed in traditional regalia while some chose to wear contemporary garb representing their tribal schools or sports teams, underscoring the diversity of Indian communities.

Over the decades, Indians have traveled to Washington in droves from its beginning, seeking justice, recognition and basic considerations for their communities. Our ancestors trekked in delegations to the city of the Great White Father.

Historical "before" photos show them dressed in traditional regalia. "After" photos show them dressed in modern Western clothing.

The notion that changing clothing would change Indians and their culture goes to the heart of the often pathological relationship between Indians and the United States.

Washington in many ways has come to symbolize these historical and cultural differences. How divinely ironic and poetic it is, then, that the National Museum of the American Indian, the16th museum of the Smithsonian Institute, now occupies one of the prime sites on the Mall.

W. Richard West, a Cheyenne member and the director of the National Museum of the American Indian, insists "no subject will be dodged."

That is a tall promise. The eyes and ears of American Indians are fixed on the museum's activities from its glamorous opening ceremonies and events to its continuing events and shows. After all, Indians have extensive experience seeing our history dodged, whitewashed, romanticized and, worst of all, denied.

The museum world has often served as an apologist for a culture that declared us unfortunate victims of an inexorable but righteous "Manifest Destiny." Museum curators sometimes put our ancestors' remains, funerary and ceremonial objects on display alongside other archaeological animal finds, furthering the notion that we were part of a long dead, barely human, past.

Placing our culture behind glass shows how easy it has been for mainstream America to ignore the genocide upon which this country was built.

At the basis of Indian philosophy is the constancy of change and the interconnected nature of life. As I once heard an elder remark, "A culture that doesn't change is a culture that dies."

Public support of the National Museum of the American Indian reflects a glimmer of hope that America is open to re-examining the underlying wisdom of this path. Indians are stepping out from behind the museum glass to offer this country important and vital knowledge. My great hope is that America will hear it.

Pember, a Red Cliff Ojibwe, is past president of the Native American Journalists Association.

Posted: September 28, 2004 -- 4:38pm EST

by: Staff reports

September 21, 2004 meant different things to different people. A day like any other, it was anything but for many American Indians gathered on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Wearing everything from full regalia to Native Pride T-shirts and jeans, the American Indian community came together in celebration. The greater community also had a strong showing of support for their American Indian brothers and sisters. During the Native Nations Procession, onlookers shouted their approval and messages of congratulations to participants. In addition to cheers and applause, Hopi veterans were greeted by a female crowd member shouting, "Thank you for my freedom." The veterans were joined by Terry and Priscilla "Percy" Baca Piestewa, parents of U.S Army Pfc. Lori Piestewa, the first female American Indian soldier killed in combat. Her children, Brandon and Carla were also part of the procession. Elders in wheelchairs and babies in strollers joined able-bodied marchers in the more than two-hour ambulatory celebration. Due to congestion, the procession made frequent stops and onlookers were rewarded with impromptu drum and dance performances. Native and non-Native members of the crowd contended with heat, crowding and over-zealous media but appeared to thoroughly enjoy the events which continued with speeches, concerts, demonstrations and tours of the museum.

Over the course of the day, Indian tacos were eaten, old friends reconnected and people witnessed American Indian culture and pride firsthand.

NMAI reflections

Indian Country Today asked a few people what significance the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian held for them.

Virgie D. BigBee of Tesuque Pueblo, N.M. said this was her first trip to Washington. "It's an honor to be recognized, to let the nation know we Native Americans have survived. It's a wonderful event, the spirit of people lives on and we are not just in the museum."

Verolga Steverson, Chickahominy, from Woodbridge, Va. said the opening of the museum is an historic event. "We are creating a memory that is spiritual. For all our forefathers that died before us -- they are with us today -- adoring this glorious event. The museum is an emblem of our heritage. It is a miracle to see all the nations coming together in peace, sharing one spirit, one union, one identity."

Alexandria, Va. resident Stephen Gonyea, Onondaga, saw the gathering as a chance to change some misperceptions. "Hopefully it'll break the stereotypes that people have that all Indian live in tipis and wear war bonnets."

Anna Haala, a Tlingit Peace Elder from Seattle event was an "acknowledgment that we are still here in spite of dominant society or [U.S.] government. [It is a] celebration long overdue."

"Ethnic boosterism"

The bad...

September 21, 2004

MUSEUM REVIEW

Museum With an American Indian Voice

By EDWARD ROTHSTEIN

WASHINGTON -- Early Tuesday morning, 20,000 members of more than 500 Indian tribes from all over the American hemisphere are expected to gather on the Mall to begin a ceremonial march toward the National Museum of the American Indian. But they will not just be celebrating the opening of the Smithsonian's new building. This Native Nations Procession, organized by the museum and forming, perhaps, the largest assembly of America's native peoples in modern times, will also be a self-celebration.

That will be perfectly in keeping with the spirit of the museum. The celebration is echoed in the museum's exhibitions. It is even asserted in the way the museum's mesa-like structure of Kasota limestone thrusts itself eastward toward the Capitol building, as if declaring -- after centuries of battle, disruption, compromise, betrayal, defeat and reinvention -- "We are still here."

In fact, that kind of assertion, along with a six-day First Americans Festival of music, dance and storytelling that the museum predicts will attract 600,000 people, is not unrelated to the museum's project. The museum will, of course, mount exhibitions that draw on the 800,000 objects that the Smithsonian acquired from George Gustav Heye's famed historical collection of what he called "aboriginal art." But its mission statement also asserts another "special responsibility": to "protect, support and enhance the development, maintenance and perpetuation of native culture and community."

In other words, the museum will advocate not just for artifacts but also for the living cultures that once created them. Most museums invoke the past to give shape to the present; here the interests of the present will be used to shape the past. And that makes all the difference.

So it is probably no accident that Tuesday's procession begins in front of the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, which still has a major collection of Indian artifacts, and heads toward the new museum. Because that is precisely the path the Indian museum's director, W. Richard West Jr. (who is a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes of Oklahoma), has had in mind. In public statements he rejected "the older image of the museum as a temple with its superior, self-governing priesthood." Instead, he said, he would create a "museum different." Indians would tell their own stories; no outside anthropologists would intrude. The objects would even be available for ritual tribal use.

Unfortunately, the result proves that a genuinely celebratory march should really be heading in the other direction.

The Museum of the American Indian has much to boast of: raising $100 million of its $219 million from private sources (a third of that from Indian tribes made wealthy from gambling casinos), a building whose initial design -- by the Canadian architect (and Blackfoot) Douglas Cardinal -- hints at what might have been, a collection of surpassing aesthetic and cultural value. And with its verve and theatricality it could easily wind up welcoming the 4 million visitors a year it anticipates.

But the ambition of creating a "museum different" -- the goal of making that museum answer to the needs, tastes and traditions of perhaps 600 diverse tribes, ranging from the Tapirape of the Brazilian jungles to the Yupik of Alaska -- results in so many constituencies that the museum often ends up filtering away detail rather than displaying it, and minimizing difference even while it claims to be discovering it.

On top of that, the studious avoidance of scholarship makes one wish that the National Museum of Natural History's American Indian Program, with its scholarly staff (directed by an anthropologist, JoAllyn Archambault, herself a Standing Rock Sioux), could have proceeded with its once-planned revision of its aging exhibits instead of having to close them down, scuttle hopes of renewal and slink into insignificance in response to its new competition.

Some of these problems seem palpable in the Indian museum's building itself, which fills the last open spot on the Mall. In 1998 Mr. Cardinal was fired from the architect job and multiple voices came into play; he called the result a "forgery" and refuses to take credit. His vision of a sweeping earth-form, shaped by nature's force fields, can still be sensed. But the northwest corner of the building is leaden, its Mall-facing facade only half-heartedly awakening as it leads toward the east-facing front. The landscaping, which includes 33,000 plants of 150 species along with various invocations of Native American elements -- a boulder from Hawaii, growing stalks of corn and a recreated Chesapeake wetlands -- is marred by fussiness.

But the exhibits are where the problems begin in earnest. The display for the Santa Clara Pueblo of New Mexico, for example, explains: "We are made up of two major clans, Summer and Winter people." But, the Pueblo curator writes: "There is no dividing line. There is just a sense." The exhibit's commentary is limited to comments like "Respect and sharing of your self is very important." One does not learn what daily life is like or even what the tribe's religious ceremonies consist of.

Similarly with the Anishinaabe, who are 200,000 strong in the Great Lakes region. The explanatory panel reads: "Everything has a spirit and everything is interconnected." The central image is a "teaching lodge" in which the tribe learns seven teachings: "honesty, love, courage, truth, wisdom, humility and respect." A diorama with life-size mannequins shows various tribe members, including children, in the lodge. They use a bowl from 1880 and a dress made in 1920, but no information is given about whether or not these objects are like the ones currently used or precisely what the "clan system" is that one comment refers to.

Such detail, apparently, was not what the tribal curators thought important. In fact, there is an astonishing uniformity in the exhibits' accounts of religious beliefs, which may have been homogenized by subtle forces within the museum itself. The building emphasizes a kind of warm, earthy mysticism with comforting homilies behind every facade, reviving an old pastoral romance about the Indian.

But these were communities that at least at one time were vastly different, which farmed or hunted, engaged in war, suffered indignity, inspired outrage. The notion that tribal voices should "be heard" becomes a problem when the selected voices have so little to say. Moreover, since American Indians largely had no detailed written languages and since so much trauma had decimated the tribes, the need for scholarship and analysis of secondary sources is all the more crucial.

But the museum almost seems afraid of distinctions. There are display cases of objects made with beads, organized with no particular logic; a beaded horse-head cover from 1900 North Dakota appears near a mid-19th-century sea-otter hat from the Aleutian Islands. One wall holds "star" objects, whose only connection is that they have pictures of stars on them. Some tribes are asked to present 10 crucial moments in their history; the Tohono Oodham in Arizona choose, as their first, "Birds teach people to call for rain." Their last is in the year 2000, a "desert walk for health."

The result is that a monotony sets in; every tribe is equal, and so is every idea. No unified intelligence has been applied. Moreover, with a net cast so wide, including South and Central America as well as Alaska, the only commonality may be the encounter with colonizers -- and even this must be simplified. The accidental epidemics that killed perhaps 75 to 90 percent of North American Indians is made far less central than the wars and forced migrations that followed. Internecine tribal wars such as those mentioned in the exhibit of the Brazilian tribe, the Tapirape, don't fit the model, either.

The focal point becomes a series of displays called "The Storm," which reflect three forces most terrible: "guns, churches and government." There are hundreds of guns and rifles on display, ranging from a 17th-century pistol to a 1985 Uzi. The church display includes nearly 200 Bibles translated into 175 languages. The government's assaults are in documents: laws, land deeds, violated treaties.

From this apocalypse one is meant to pass to an anthology of current-day tribal life, which includes examples of casinos, ice fishing, social clubs and platitudes.

But a great opportunity was missed in this museum. Individual tribes could have been explored in depth. Even the "storm" could have been illuminated with more detail rather than by just invoking the forces involved.

The museum, though, seems satisfied with serving a sociological function for Indians of the Americas. It may indeed succeed, because it has packaged a self-celebratory romance. Understanding though, requires something more. It is not a matter of whose voice is heard. It is a matter of detail, qualification, nuance and context. It is a matter of scholarship.

Shards Of Many Untold Stories

In Place of Unity, A Melange of Unconnected Objects

By Paul Richard

Special to The Washington Post

Tuesday, September 21, 2004; Page C01

The Bible being silent on Indian origins, the Puritans concluded that the people they encountered in the Massachusetts woods were of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, and greeted them in Hebrew. Soon they realized that they had somehow got it wrong.

The hope-filled viewer who tries to make some sense of the National Museum of the American Indian will feel as stymied, as confused.

What's it like?

Well, the new museum that opens to the public today is better from the outside than it is from the in. Its exhibits are disheartening, their installations misproportioned, here too sparse and there too cramped. Eight thousand varied objects, some spectacular, are offered to the eye. What's missing is the glue of thought that might connect one to another. Instead one tends to see totem poles and T-shirts, headdresses and masks, toys and woven baskets, projectile points and gym shoes, things both new and ancient, beautiful and not, all stirred decoratively together in no important order that the viewer can discern.

The great material culture of the natives of this hemisphere is rich beyond imagining, but not much is on view. The museum owns 800,000 Indian objects. Where are they? Mostly absent. Mostly absent, too, is the brain food one expects from good museums. This one teaches few crisp lessons. Too often its exhibitions are a blur.

Hundreds of curatorial minds, those of Indians mostly, were consulted on its contents. Director W. Richard West Jr. says his museum "in a systematic, consistent, rigorous and scholarly way," has attempted "to put native peoples themselves, in their first-person voices, at the table of conversation." But "systematic, consistent, rigorous and scholarly" are not words that well describe the shows that have resulted. Too many cooks. The eye should have been offered a feast of many courses. Instead it's served a stew.

What's best about the building is that it isn't just a museum. It's a reparation, and a reconciliation. It soothes the nation's conscience as its limestone undulations soothe the strictness of the cityscape. It brings to the Mall a pond with lily pads, a waterfall, tobacco leaves, cornstalks and big rocks. And then you step inside.

The big domed room you enter, named Potomac, may come alive when performances are held there. But now it is bare. Beyond, a broad staircase beckons. You climb and find — a shop. An expensive one. The whole building stresses shops, and rooms in which to gather, and in which to eat, much more than it does art.

On the third floor, finally, there are some Indian things to see — a gangiluk (a 19th-century Aleutian hunting hat made of wood and walrus whiskers), a Victorian pincushion and moccasins. All of these have beads on them. One can see no other reason why they're side by side.

Indians do beadwork, that's the point. They also chipped at rocks, and for this reason we are shown scores, or perhaps hundreds, of arrowheads and spear points, all swirled into a pattern as if they had just joined a school of fish. Who precisely made them? How old are they? From where do they come? By now one understands — because answers aren't provided — that one is not supposed to ask.

Like Hindus and Assyrians and everybody else, Indians all over the hemisphere look up at the heavens. Hence we get a room whose pinpoint ceiling lights suggest the starry sky. In it are a pipe and a woven basket and other things with stars on them. That seems to be the only connection that these varied objects share.

The mind is getting hungry. It wants something to chew.

Indians make dolls. So here's a case containing more than 200 dolls. One is a Hopi kachina from the 1960s. Such dolls have long been used to give children of the tribe a sense of unseen spirits. Beside this doll is another, a blonde in a bikini, that might serve to teach a child about Marilyn or Barbie, but isn't spiritual at all. The Apache figure next to it, circa 1880, has a horsehair plume where it ought to have a head. Are you getting the point? Indians make dolls.

The "Our Lives" exhibit, in which various tribes suggest the various ways they live, is more coherent, and more poignant. From northern Canada is an Igloolik kitchen, which wittily includes a couple of aluminum Coke cans, a flashlight (it stays dark in winter in the Far North), unbreakable plastic bowls, a pair of scissors and a teapot. Good for them. Still theirs is not the sort of offering that many will return to see time and time again.

The museum doesn't nourish thought. "Native Modernism: The Art of George Morrison and Allan Houser," the two-man retrospective on the third floor, is a notable exception. It is well focused and well labeled. At the Indian Museum few shows are as clear. There is no useful way to link all the baseball caps and arrowheads, Niagara Falls souvenirs, old gold and new totem poles, macaw feathers and turkey feathers and Spanish swords and casino chips that have been stirred into the pot.

But a point is being made. There is an agenda in this mix. It may be, for once, an Indian agenda, but it's an agenda nonetheless.

We keep seeing the Indian through lenses cracked by rickety, romantic or contradictory assumptions. We've been doing so for centuries. It's built into our heritage; it's part of who we are. The museum does the same.

For half a bloody century, from 1859 to 1909 — while squashing his culture, while shooting, deceiving and intentionally infecting him, while driving him to drink and into reservations — we put the Indian on the penny where other nations put the king.

From 1913 to 1938, after slaughtering the buffalo, the Indian's fellow victim, we put that creature on our nickel and will do so soon again.

We want it both ways. We treat the Indian with disdain while appropriating his special strength with missiles called the Tomahawk and sedans called the Pontiac and ball teams named the Redskins and the Indians and the Braves. The museum wants it both ways, too.

Here's the contention it continually asserts:

Indians are all different; overarching Indianness makes them all alike.

Well, which is it? The museum can't make up its mind.

That Indians are fabulously varied is obvious. As fisherfolk and astronauts, as nomads and attorneys, as dwellers in the woodlands, the deserts and the Arctic, how could they not be? Try to imagine a mass of humans more vibrantly diverse.

The rest of the assertion — that by virtue of their history, and by virtue of their blood, all Indians share an overarching "Indianness" — is a lot harder to swallow.

What is this Indianness? Well, according to your CDIB (Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood issued by the Bureau of Indian Affairs), it comes with your genes; you inherit it. A thousand cultures share it. Indianness exists in people now alive and those dead 12,000 years. It is ineffably mysterious. No one can describe it except in generalities. Here are some from museum publications:

"Native people believe that unseen powers and creative forces formed the Earth." "Native Americans of the past and present consider many places holy." "They manifested their beliefs through ceremony and ritual." They use "the circle as a symbol of unity." "Monsters appear in many American stories." "Sun . . . is a symbol of abundance, well-being, fire, strength, brilliance, and light."

Indianness is not just vague. It also is so elastic you can stretch it to cover Inuit walrus hunters, Mohawk skyscraper constructors, public-information specialists, plumed Aztec kings, Mississippi mound-builders, political activists, filmmakers, Navajo code-talkers, surfing Hawaiians, art professors, bus drivers and all the other individuals that the Indian Museum claims to represent.

I don't buy it. To be accepted officially as a Nez Perce, according to Title Six, the Enrollment Ordinance, you need at least one-fourth Nez Perce blood. What about the other three-quarters? The notion that one's spirit, one's values, one's identity, arrives automatically with whatever blood-percentage defines you as an Indian smacks too much of octoroons and pass laws in South Africa and sewn-on Stars of David.

Of course one of the museum's problems is the extent to which it does not discriminate. Are ancient painted bowls made before the white man came and those thrown for the gift shop equally authentic? Should bathing-beauty dolls and bracelets for the trading post and beaded ladies' purses be granted equal value? Here the answer's yes.

No wonder the Indian Museum seems sort of embarrassed by its permanent collection, to which it gives short shrift. Only 1 percent of it is on view; much of that is squeezed into narrow cases stuck out in the halls. You'll have to make an appointment to visit the museum's treasure house in Suitland to see the other 99 percent.

Too often in these hallways — because the labeling is awful — you have no idea at all what it is you're looking at. To find out you must first retreat, and wait to touch a TV screen, sprinkled with small photographs. Photographs! The real thing itself is there only feet away, but if you want to know who made it you have to break your concentration to fiddle with 21st-century interactive digital technology. Soon you'll want to scream.

Aztec, Olmec and Mayan art, and carvings for the potlatch, and woodland Indian "banner stones," and Costa Rican gold — amazing shows of Indian things have been displayed before in other Mall museums. Their beauty was enough to make anyone with eyes treasure Indian art and seek to learn something about it. Here that sort of linear Eurocentric art-historical thinking is generally disdained.

This is not an art museum, that's clear. It's not a history museum, either. Its whole thrust is ahistorical. What it is, instead, is a unity museum. Unity helped build it, unity enabled the many tribes involved to influence the government: Unity, for Indians, may be the sharpest blade they have. The key, the pounded message that their museum delivers — see, we have survived; we are Indians all together; we are allied and we're one — says much about the forces that created the museum, and next to nothing useful about the Indian past.

But then the Indian Museum doesn't really believe in the past. "Europeans," it tells us, "emphasize a sequential presentation of events or ideas," while "for Native nations of the Americas . . . the circular manner of perceiving past and present, rather than seeing one event simply follow another, is most important as a way to think about Native American history."

But the Indian past existed, and the hand-in-hand Indian unity proclaimed in the museum was not a major part of it. America, before the Europeans came, was not Edenic. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who imagined that it was, may have read a lot about the Golden Age in Ovid and about Arcadia in Virgil, but he knew nothing of ancient Mexico. His sweet idea is fiction. It's still alive in this museum (the lily pads, the waterfall), but it's fiction nonetheless.

Aztec rulers ate their captives. Mayan kings warred ceaselessly. Slavery was common before the white man came. The ancient cliff dwellers of the Southwest lugged their food and water up ladders for a reason; they didn't come to dwell high up on sheer canyon walls because they liked the view.

Prettily presented in the "Our Peoples" display on the fourth floor are scores of fearsome weapons — axes, daggers, flintlocks, carbines and six-shooters — but who these arms were used by, and whom they were used against, and why, characteristically is not much discussed.

These are the museum's early days, of course. Much of the vapidness of these exhibits is fixable. Grand museums often take years to find their way.

Remember "The End of the Trail," James Earle Fraser's 1915 bronze of a dejected Indian on a sagging horse? Not so very long ago the Indian was supposed to either disappear, poignantly, melodiously like "The Last of the Mohicans," or become just like the rest of us. Both options were declined. That, at least, is clear in the new museum on the Mall.

The Indians have lost most of their old languages and most of their old lands, but material things survive, that's why we build museums. Indian objects can be eloquent. They have great stories to tell — of cruelty and sweetness, technology and magic, survival and defeat. They may not all be true and may not all agree. But they deserve to be presented with enough precision and discrimination so that they are believed.

© 2004 The Washington Post Company

Indian Museum's Appeal, Sadly, Only Skin-Deep

By Marc Fisher

Tuesday, September 21, 2004; Page B01

The sand-toned, curved limestone walls of the new National Museum of the American Indian make it the most sensuous and serene structure on the Mall, a powerful and immediate sign that this nation's roots lie deeper than Roman temples and English gardens.

But as alluring a reminder as this building is of who was here first, the inside of the museum — the story it tells — is an exercise in intellectual timidity and a sorry abrogation of the Smithsonian's obligation to explore America's history and culture.

The exterior of the Indian museum deserves to rocket to the top of the list of Washington must-sees. But inside, the three main exhibits fail to confront the clash between foreign colonists and the native people they found here. There is no effort to trace Indians' evolution from centuries of life alone on this land to their place in reservations and among the rest of us today.

Instead, the Smithsonian accepted the trendy faux-selflessness of today's historians and let the Indians present themselves as they wish to be seen.

"A history is always about who is telling the stories," says the opening to the exhibit, "Our Peoples." "Official histories often ignored Indians completely. Others portrayed us as primitive and cruel." A introductory film concedes that this museum "like all makers of history, has a point of view, an agenda. We offer self-told histories of selected native communities."

The narrator asks visitors to "view what's offered with respect, but also with skepticism."

That's the right spirit, but the museum fails to give visitors the basic tools needed to ask good, skeptical questions. There's not nearly enough fact or narrative to give us the foundation we need to judge the Indians' version of their story.

So when the Campo Band of Southern California presents an exhibit on its Golden Acorn Casino, a case displays a casino baseball cap, T-shirt and gambling chips, but nothing about the economic impact of Indian casinos, non-Indian consultants who siphon off profits or gambling addiction. Instead, we get a single sentence: "Some feel that gaming is not our way and will bring new problems to our territories."

A display about the Mohawk ironworkers who build Manhattan skyscrapers asks why generation after generation of Indians can work so well at such dizzying heights. But instead of offering any science or sociological theories, the museum merely quotes an Indian named Kyle Karonhiaktatie Beauvois saying, "A lot of people think Mohawks aren't afraid of heights; that's not true. We have as much fear as the next guy. The difference is that we deal with it better." Gee, thanks.

Poverty and substance abuse, domestic violence and unemployment — the social ills that developed over generations of displacement, discrimination and disconnect from the wider society are mentioned, but not explored.

Rather, we get repetitive stories of survival, of how tribal customs and rituals are nourished today — a painfully narrow prism through which to view American Indians.

The museum feels like a trade show in which each group of Indians gets space to sell its founding myth and favorite anecdotes of survival.

Each room is a sales booth of its own, separate, out of context, gathered in a museum that adds to the balkanization of a society that seems ever more ashamed of the unity and purpose that sustained it over two centuries.

The Holocaust Memorial Museum started us down this troubling path. A first-rate endeavor with a rigorous, probing approach to history, the Holocaust museum — a privately funded enterprise on government land — should nonetheless never have been given a spot near the Mall. Its location there opened the gate for the deconstruction of American history into ethnically separate stories told in separate buildings. Museums of black and Hispanic history are in the works.

American history is a thrilling and disturbing sway from conflict to consensus and back again. But the contours of the battle between division and coalition are too often lost in the way history is taught today. Now, sadly, the Smithsonian, instead of synthesizing our stories, shirks its responsibility to give new generations of Americans the tools with which to ask the questions that could clear a path toward a more perfect union.

Oct. 5 (Bloomberg) — Like everything else these days, museums are mostly about money, so it's no surprise that when you enter the Smithsonian Institution's new National Museum of the American Indian, which opened Sept. 21 in Washington, D.C., you walk through a cavernous domed atrium that looks as if it were designed to be the sumptuous setting for candle-lit fund-raisers. You can almost hear the clink of high-ball glasses and the jing-a- ling of jewelry.

No, wait. That jing-a-ling of jewelry must be coming from just beyond the atrium, where the Chesapeake Museum Store sells bracelets and earrings and necklaces of silver and jade for $950 and up. The Chesapeake store is not to be confused with the Roanoke Museum Store, which is on the mezzanine above.

Follow the path past the Chesapeake store, past the Mitsitam restaurant (Piscataway for "Let's eat"), and you'll find an ATM, right next to the elevators. And not a moment too soon, either. Lunch at the Mitsitam can easily run $20 or more per head.

By this time, having circumnavigated the entire first floor of the museum, one of the largest on the national mall, you still won't have seen a single museum exhibit; all the exhibits are far above you, on the third and fourth floor, an elevator ride away. But you will have had multiple opportunities to spend money.

The Last Museum

In fairness, it must be said that the National Museum of the American Indian was not designed solely to accommodate the new national pastime of shopping. It is also intended to make a political and sociological statement —though not a terribly coherent one.

Its opening last month sparked headlines around the U.S., for good reason. The building itself is a spectacular creation of curving limestone walls, surrounded by rock gardens and waterfalls and exotic plantings. Filling the last open site on the national mall, in the heart of the nation's capital, it will be the final addition to perhaps the greatest concentration of museum space in the world, anchored by the National Museum of American History and the National Gallery.

Inside, however, it bears little resemblance to those more traditional neighbors, which exist to display artifacts notable for their beauty or cultural significance as a way of elevating or amusing the customers.

The Indian Louvre

The National Museum of the American Indian, in contrast, aims not to elevate or amuse but to lecture.

It didn't have to be this way. The museum's nucleus is the world's largest collection of American Indian artifacts, amassed by George Gustav Heye, a New York investment banker, before his death in 1957. Some scholars have declared Heye's collection, in its variety and excellence, to be the Indian equivalent of the Hermitage or the Louvre.

The Heye museum in Manhattan was always too small for its founder's collection, which is one reason Congress in 1989 authorized the construction of the new museum.

Yet today only a small fraction of the Heye works can be seen on the mall. The rest — including pieces of surpassing beauty and historical interest, such as Sitting Bull's pictographic autobiography — have been trucked to a warehouse in Suitland, Maryland, where they sit unseen by the general public.

High Concept

Instead, once you make it to the upper floors and wander the museum's high-concept exhibits — "Our Universes," "Our Peoples," "Our Lives" — you find a jumble of displays designed to reflect the lives Indians lead today, giving off an unmistakable air of ethnic boosterism. Almost all the exhibits have been designed by native peoples themselves, with a minimum of curatorial oversight, and it shows.