Continuing the analysis of the 9/11/01 terrorist attack on America....

Continuing the analysis of the 9/11/01 terrorist attack on America.... Continuing the analysis of the 9/11/01 terrorist attack on America....

Continuing the analysis of the 9/11/01 terrorist attack on America....

Our nation is chosen by God and commissioned by history to be a model to the world....

George W. Bush, B'nai B'rith convention, 8/28/00

As if calling for war against a criminal and his henchmen weren't enough, Bush ratcheted up his rhetoric to new heights. From the LA Times, 9/18/01:

AFTER THE ATTACK

When Evil Itself Becomes the Primary Foe

Language: Some experts feel Bush may be over-stating U.S.' mandate and capabilities. Others say he is within boundaries.

By MARY McNAMARA and LYNELL GEORGE, TIMES STAFF WRITERS

On Friday, George W. Bush made as broad and epic a statement as a president could. In the wake of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, he said, "Our responsibility to history is already clear: to answer these attacks and rid the world of evil."

Repeatedly characterizing the tragic events and the forces behind them as "evil" and "evildoers," Bush has given his rhetoric biblical, even mythic, resonance. In times of war and international conflict, foes often are characterized as evil—Ronald Reagan famously referred to the Soviet Union as the "Evil Empire"—but historians could not recall a president naming evil itself as his primary opponent.

Even when compared with President Wilson's pledge to make the world safe for democracy, Bush's declaration could seem symbolic of the very hubris that critics of the United States claim engendered the hatred behind the attacks. Still, while some religious leaders, historians and cultural analysts feel that Bush may be overstating the country's mandate and its capability, others believe he is well within the boundaries of appropriateness—as long as he recognizes the power of the sentiment such words evoke and shows responsibility in quantifying his goals as time goes on.

"The targeting of innocent citizens in peacetime fits everyone's definition of 'evil,' " said Rabbi Abraham Cooper, associate dean of the Simon Weisenthal Center in Los Angeles. "But once you invoke the term, you have a greater moral responsibility to make sure you're not demonizing a people or a faith. Certainly, as rescuers continue to find body parts, as so many funerals take place with empty caskets, the word 'evil,' with all its dangers and connotations, seems perfectly appropriate."

Although she too understands why last week's horrors can evoke such a powerful word, Diana L. Eck, professor of comparative religion at Harvard University, cautions against its use as a rallying cry. "There is a danger using a term like this," said the author of "A New Religious America."

"It signifies the worst that we can imagine. 'Evil' is a crusading term."

The president's pledge to "rid the world of evil," she said, "is not a response that is possible by human beings. That is beyond what we can do." In fact, she thinks the president should reconsider his use of war rhetoric altogether. "I think that the language of crime is very good for this," she said. "This is a crime against innocent human beings."

Robert Schmuhl, a professor of American Studies at the University of Notre Dame, cannot think of any other president who has gone so far in retaliatory rhetoric. Reagan, he said, vilified the "Evil Empire," but then "evil" was an adjective, not a noun.

The president, he suggested, should keep in mind that the international community may not be willing to join what essentially is a crusade. "And as religious leaders will tell you, there are many other forms of evil beyond what we witnessed last week, as horrible as it was."

William Epps, pastor of Second Baptist Church in Los Angeles, agreed. "You cannot diminish how awful this deed is, but [Bush] should quantify it as the evil of terrorism. You're not going to eradicate evil. The evil of terrorism maybe. [The evil] of drugs, maybe, but evil? We have to look at what we've done to incur the anger and wrath of others."

Yet, some think Bush has indeed chosen carefully, and chosen well.

" 'Evil' is not a subtle word," said Barbara Wallraff, a linguist and senior editor at the Atlantic Monthly. "But this is not a subtle moment. It makes a lot of sense that he would choose that word, would choose to repeat that word."

Comment: The moment may not be subtle, but the problem facing America is. But Bush isn't a subtle thinker—or a thinker, period—so that may explain his choice of words.

When she heard Bush vowing to find and punish the evildoers, she said, she thought his language sounded a bit "antique and biblical," but as a politician, Bush's task is to set up a campaign that is above criticism. "And no one is going to disagree with being against evil," Wallraff said. "It's a carefully chosen word, because we don't know who exactly we're up against and we don't want to tie it to Islam, even Islamic extremists. . . . Certainly we're leaning on the Taliban, but we want them to go along with us. When you think about it, he couldn't have chosen a better word."

While Bush's first use may have been a gut reaction, his subsequent repetitions have been undoubtedly calculated. According to Stuart Spencer, a political consultant who worked with President Reagan, political figures tend to choose words that have particular personal definitions but use them strategically. When Reagan decided to call the Soviet Union the Evil Empire, Spencer said he was nervous. "I didn't think the American public would accept it."

But many of them did, and Spencer believes they also understand exactly what Bush means by his words. "He is making a point that these are evil people; they don't do things in an upfront manner."

Bush's "task" at the moment isn't to be a politician and put his policies beyond criticism. His task is to be a leader or a statesman. If he wants to "calculate" his words to further his agenda, I'll be happy to calculate mine when his agenda fails. And it surely will fail since, as William Epps said, you can't eradicate evil.

Historian Simon Schama thinks anyone who is arguing semantics at this point "should take a powder." During a segment on Canadian radio, he said, he took issue with English writer Margaret Drabble over this very subject.

"Margaret Drabble said it was unhelpful, and I got rather angry at this. For one thing, if this isn't evil, then I don't know what is. And if people are going to use superlatives, if people like Drabble are going to say super-super-naughty-wicked-bad—and they are—then they might as well say 'evil.' "

Okay, I'll bite on that one. If you look up "evil" in the dictionary, you should see a picture of the Holocaust next to it. If killing 3,000 people in a holy war is "evil," how would Schama describe a genocidal purge 1,500 times more deadly? "Really, really, really, really evil?"

"Evil is any abstraction that enables you to look at someone and not see the person," said Lee Thorn in "Reconciliation" (Turning Wheel magazine, Fall 2000). In other words, it's a way to demonize a person into an object, which you can then dispose of like a crushed soda can.

Bush, he said, could be "a bit more economical" in his use of the word. The author of "Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution," Schama thinks what has happened, and what is yet to happen, is far more complicated than a battle between good and evil. "Basically this is a rejection of the 'Enlightenment,' " he said. "Voltaire saw the main conflict as being between societies of tolerance and societies of obedience. That is what we're facing. [The terrorists] want us dead because we're unacceptably tolerant."

Now Schama is getting warmer. If the situation is far more complicated than "good vs. evil," perhaps he should find a better word than "evil" to describe the terrorists. Sounds like he's agreeing with Margaret Drabble that the word is unhelpful.

Western culture may be "unacceptably" tolerant, but it's also unacceptably acquisitive, arrogant, and imperialistic. In some ways it's "evil" also. So the best word to describe the terrorists depends on their goals. Are they trying to conquer or destroy Western culture, which isn't their right? Or are they trying to rid themselves of Western influence, which is?

Only the first goal is arguably evil, because it imposes on others that which they don't want. If Islamic fundamentalists believe they're in a legitimate war, their goals (if not their methods) become legitimate also. America killed a lot more innocent people at Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Dresden, so motive is everything.

William J. Bennett, self-proclaimed morality czar, is another who has claimed the terrorists are uniquely evil. I've posted his arguments and, as always, refuted them.

Reactions to Bush's "evil"

From "When the Ayes Have It, Is There Room for Naysayers?" in the LA Times, 9/28/01:

"The toughest thing for me," [activist Daniel Berrigan] said, "is the official line that terrorism arises from a kind of spontaneous combustion against the virtuous." That notion, Berrigan said, "excludes the thought that one appropriate response is a national examination of conscience. This is just the latest extension of an older American idea that the evil kingdom is always somewhere out there and the virtuous kingdom is always somewhere within our borders.

From the letters to the LA Times, 11/3/01:

President Bush should now leave off using the word "evil" to describe the terrorists. No one doubts that these madmen are diabolical. And though theologians may argue that "evil" is the technically correct term of art, this is not a nation ruled by clerics. We are represented and governed by secular officials whose public pronouncements must be free of the taint of metaphysics. The mullahs label us the Great Satan based on their radical dogma, but we must not respond in kind by hurling back pious epithets. To brand the terrorists as evil, rather than just our mortal enemies, assigns them a greater significance than they merit. They are not the manifestations of some cosmic force, but merely heinous criminals who must be coldly and clinically eradicated.

BRUCE MENDENHALL

Sunnyvale, Calif.

From "The Political Clock Is Ticking" by Kevin Phillips. In the LA Times, 11/11/01:

The outbreak of terrorism itself deserves a more sophisticated analysis than Wyatt Earp-type posturing about "huntin' down" evildoers. Since the origins of "terrorism" in 1790s revolutionary France, its three peaks—in the 1790s, in the years between 1880 and 1920 and then in the 1960s and 1970s—all overlapped with seething opposition to aristocratic, royal and capitalist establishments (and conspicuous consumption), on the one hand, and a ripeness for war, on the other. Historically, terrorism has been an introduction, not a finale. Washington's task is to thwart any such evolution, not assist it.

Bush finds more "evil"

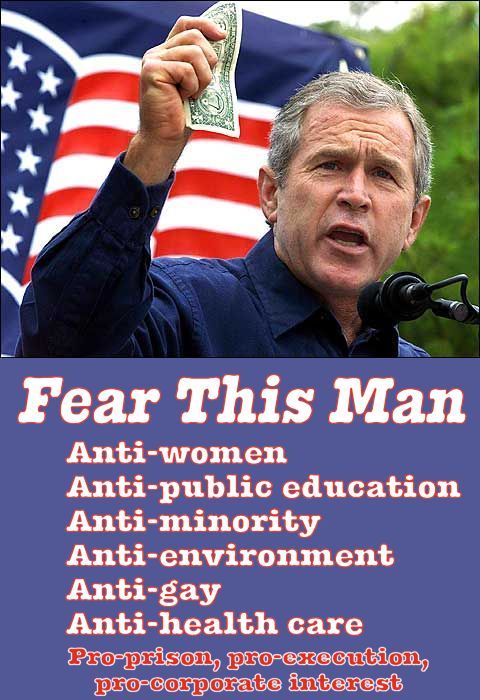

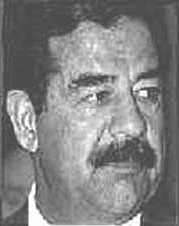

When Bush couldn't immediately locate Osama bin Laden, he needed some justification to continue his perpetual war state. Hence he labeled Iran, Iraq, and North Korea—three unrelated countries—as the "axis of evil." His rhetoric was as ill-advised this time as it was before.

From the LA Times, 1/21/03:

THE NATION

'Axis of Evil' Rhetoric Said to Heighten Dangers

Many foreign policy observers think Bush's phrasing, although effective on the home front, caused serious damage abroad.

By Maura Reynolds, Times Staff Writer

WASHINGTON — It was a catchy phrase. Perhaps too catchy.

A year after President Bush used the State of the Union address to declare Iraq, Iran and North Korea an "axis of evil," the phrase has taken on a life of its own. With this year's address scheduled for Jan. 28 and the U.S. on the cusp of war with Iraq, the legacy of the "axis of evil" weighs heavily on the speechwriters and policy-makers hard at work on Bush's speech.

Even critics agree that the "axis of evil" was a clever piece of rhetoric in explaining the president's policies to the American people. But as foreign policy, there is wide consensus that it exacerbated the dangers it attempted to contain.

"It was a speechwriter's dream and a policy-maker's nightmare," said Warren Christopher, secretary of State under President Clinton.

The phrase caused immediate controversy. A year later, many experts say it's clear it also has caused real damage.

"It was harmful both conceptually and operationally," said Graham Allison, government professor and former dean of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. "Conceptually, the 'axis' suggested a relationship among the entities that doesn't exist. More important, operationally, the reaction of the world and the North Korea debacle demonstrates that it was a mistake."

The "axis of evil" language upped the rhetorical ante significantly. Some believe it played a role in undermining Iran's moderate leaders and squelching the country's nascent democracy movement. Many believe it helped provoke North Korea into nuclear confrontation.

The man who half-coined the phrase was speechwriter David Frum, who left the White House a few months after Bush used it. In a recent book, Frum said his assignment for the State of the Union last year was to extrapolate from the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks to make a case for "going after Iraq."

For inspiration, he thought back to Pearl Harbor and pulled a copy of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "date which will live in infamy" speech off the shelf. And he found what he was looking for.

"No country on Earth more closely resembled one of the old Axis powers than present-day Iraq," Frum wrote. "And just as FDR saw in Pearl Harbor a premonition of even more terrible attacks from Nazi Germany, so Sept. 11 had delivered an urgent warning of what Saddam Hussein could and almost certainly would do with nuclear and biological weapons."

One Country No 'Axis'

The argument was emotional and powerful. As Frum put it, and Bush eventually said it, the lesson they took from Sept. 11 was that "the United States of America will not permit the world's most dangerous regimes to threaten us with the world's most destructive weapons."

But Hussein's Iraq wasn't an "axis," which in the popular mind consists of three aligned powers. To fill it in, Frum added two other troublesome nuclear wannabes — Iran and North Korea. Frum acknowledged there was no formal alliance among the three, as there had been among Germany, Japan and Italy during World War II, but argued there were still important similarities.

"The Axis powers disliked and distrusted one another," Frum wrote. "They shared only one thing: resentment of the power of the West and contempt for democracy."

So the phrase he came up with was "axis of hatred." He said his boss, chief speechwriter Michael Gerson, changed it to "axis of evil" to match the theological language Bush had adopted after the terrorist attacks.

The phrase struck a chord — first with Bush, who liked it and made it his own, and with the president's supporters and advisors.

"The president was pointing to common characteristics between some states, and these are brutally repressive regimes that care nothing about the aspirations or even the well-being of their people," national security advisor Condoleezza Rice said.

But for many others, the analogy was a stretch. No matter how much of a menace Iraq might pose, critics say it was careless and simplistic to lump it together with Iran and North Korea, countries with which it had next to nothing in common.

The leadership is secular in Iraq and religious in Iran, and the two countries — far from being allies — are sworn enemies. As Iran's leaders appeared to moderate their anti-American stance in recent years and a democracy movement appeared, Iraq grew more repressive and belligerent. North Korea, meanwhile, remains locked in the grip of an anachronistic communist dictatorship and, far from colluding with other nations, may instead be the most isolated country in the world.

Richard K. Betts, director of the Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University, said it was obvious for a long time before the speech that the Bush administration was focusing on the dangers posed by "rogue nations" to a degree many experts and allies considered excessive.

The speech "lumped together three countries that the people in the administration were already thinking about in the same way," Betts said. "Everyone knew before that this was the way they thought, but [the speech] did it in a pithy way that made it hard to ignore."

At least in public, White House officials reject the charge that the speech caused damage. They note that North Korea was pursuing a uranium-based weapon program in violation of its international commitments long before Bush uttered the "axis of evil" phrase.

Phrase Disappears

"It's rather impossible to connect those dots," White House Press Secretary Ari Fleischer said this month. "North Korea took the action before the president was even in office."

Nonetheless, in what could be seen as a tacit acknowledgment of error, White House officials appear to have dropped the phrase from their lexicon. Bush himself has not used it since August.

In fact, a year after putting Iraq and North Korea in the same camp, administration officials now are at pains to insist that the two aspiring nuclear powers really are different after all: We need to deal with North Korea diplomatically, they say, but we may need to go to war against Iraq.

Having put the three countries together in one basket "makes it more difficult to deal with them on a different basis," Christopher said.

Another difficulty, experts say, was the choice of the word "evil."

"It's too heavy and radioactive a word," said Joseph Montville, director of the Preventive Diplomacy program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. "You can't make a deal with evil. You can only kill it."

In other words, it sends a message to friend and foe alike that the United States will not negotiate. And domestically, it makes it easy to explain why the country needs to attack Iraq, but it makes it hard to explain why the administration needs to engage with North Korea.

Dae Sook Suh, a Korea expert at the University of Hawaii, said it would be wrong to lay all blame for the North Korea crisis on Bush's phraseology. Instead, he said, a crisis was bound to arise during Bush's tenure because the 1994 agreement freezing North Korea's nuclear program was gradually unraveling. What the "axis of evil" speech did — along with other unvarnished language, such as Bush calling North Korean leader Kim Jong Il a "pygmy" — was accelerate it.

Words Seen as Rude

Blunt speech may be admired in the United States, Suh noted, but in Asia it is considered rude, threatening and unseemly, especially for a president.

"Bush may be going the right way in policy terms, but I don't applaud him for using this cowboy language in diplomatic circles," Suh said.

In retrospect, the "axis of evil" phrase appears to have caused the most damage to relations with North Korea. Montville said it is ironic, because putting North Korea into the "axis" seems to have been something of an afterthought.

"It was [added] to avoid intensifying the suspicion of Muslim countries that the war on terrorism was a war on Islam," Montville said.

This year, he posited, speechwriters and presidential advisors are likely to be more cautious. The country already is fighting a war on terrorism, threatening another with Iraq and trying to avoid one with North Korea.

"The temptation is to be rhetorically clever. But we can't afford the emotional satisfaction of using phrases and words that make headlines the next day but cause us problems later because we fail to think about the implications of the language that we use," Montville said. "A lack of prudence can put you in a box down the road."

Copyright 2003 Los Angeles Times

Why "evil" talk is dangerous

From Nazis to terrorists, our enemies are always "evil." From the LA Times, 12/4/01:

It Is Crazy to Curtail Due Process Rules

Don't gut civil liberties by invoking evil.

By ROBERT SCHEER

How short the memory of even our more respected pundits. Take Thomas L. Friedman, who argued in the New York Times on Sunday that because we now face an enemy unlike any other, "Atty. Gen. John Ashcroft is not completely crazy in his impulse to adopt unprecedented, draconian measures and military courts to deal with suspected terrorists."

The argument, which polls suggest has vast public approval, is that the terrorists are uniquely evil, and while democratic measures may have worked just fine with other enemies, they won't work this time around.

"When we were at war with the Soviet Union," Friedman writes, "we saw the world differently, but there were still certain basic human norms that the two sides accepted. With Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda, we are up against radical evil—people who not only want to destroy us but are perfectly ready to destroy themselves as well. They are not just enemies of America; they are enemies of civilization." But if the Soviets were not also enemies of civilization, why did Ronald Reagan define them as the "Evil Empire"? Why did his CIA arm Muslim fanatics to wage holy war against godless communism in Afghanistan?

If the Soviet leaders were not into "radical evil," why did Reagan insist that we build missile defenses against an enemy he claimed was serious about initiating and winning a nuclear war, despite the inevitable destruction of all modern life? The argument was that Russian communists, like Chinese, Vietnamese and Cuban communists, did not value human life.

The assumption that we are at war with a uniquely evil force is dangerous precisely because it is again used to defend undemocratic measures that will destroy our society as effectively as any enemy might hope to.

What we are hearing is also the argument used during World War II to justify rounding up innocent Japanese civilians, who were said to be members of a uniquely evil race that produced suicide pilots.

Speaking of radically evil people, what about the German Nazis, only a small portion of whom were punished for the most ghastly crimes in human history? The vast majority of Hitler's fanatical supporters easily transitioned to life in the free world.

Evil does not stand still in one person, society or time, permitting it to be killed with a stick as in a childish fantasy. Even if one associates its occurrence with the work of the devil, there is in Christian religion the notion of winning that battle, raging even within one's own soul, and finding redemption.

A good thing too, or we would have a very hard time working with world leaders such as Ariel Sharon, Yasser Arafat, Vladimir Putin, Gerry Adams and Nelson Mandela, all of whom were once associated with "terrorism."

To suggest that evil is immutable in a huge category of people called "Muslim fanatics" may appear to be a tough-minded stance, but it is naive. Evil is complex in origin, and its source requires serious examination.

True, the hard-core leadership of Al Qaeda and the Taliban are war criminals. However, they should be tried in a fair and public manner, as were the Nazis at Nuremberg. What greater example of extending due process to people with whom we did not have shared values.

What is "completely crazy" is for Ashcroft to abandon the standard of due process—which would fully and publicly document the crimes—in favor of "draconian measures." That only serves the terrorists' purpose to destroy Western democracy.

*

Robert Scheer writes a syndicated column.

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

Summing it up, "ignorance is bliss" for many Americans. The attitude is central to the cowboy mentality of Reagan, Bush, and anyone else who thinks the world is black and white.

From Mark Morford's column in SFGate, 9/13/02:

We just don't want to know. The nuances, the details, the messy convoluted and often criminal truths, the Saudi Arabian oil dependency, the rivers of money, the true engines of the global economy. The gap is there, is getting darker, and we just shrug and sigh and shed our tears and hope whatever the government does, it doesn't do it in the street and frighten the horses.

We really want to believe it's as simple as Saddam evil, America good, eye for an eye, let's get the terrorist bastards no matter what, how dare they taint our pure noble innocence, our leaders have our best interests at heart, oh please please please don't tell me otherwise.

More on ridding the world of "evil"

Americans are from Mars, Europeans are from Venus: "Americans generally split the world into good and evil, friends and enemies."

How the World Sees Americans: "[T]he world's superpower...has a childlike understanding of everybody else."

Related links

Terrorism: "good" vs. "evil"

Kill those towelheads!

America's exceptional values

America's cultural mindset

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.