From the LA Times, 3/7/01:

From the LA Times, 3/7/01: From the LA Times, 3/7/01:

From the LA Times, 3/7/01:

Triggers of Violence Still Elusive

Long-term studies now identify 'risk factors' that lead youths to lash out. But no one can predict an individual's behavior.

By ROSIE MESTEL, Times Medical Writer

A decade or so ago, nobody knew if there was any solution to youth violence in America.

As Monday's school shootings in Santee illustrate, researchers still have much to learn before society can stop this and other kinds of senseless killing and maiming.

But by tracking thousands of children in long-term studies, social scientists have homed in on dozens of "risk factors" for violence. They've brainstormed new ways to help ward off or quell violent behavior. And they have taken the crucial next step and tested dozens of interventions in scientifically designed studies.

The science reveals that some programs work well. Some don't. And some can backfire.

Many of these findings were reviewed in a recent report of the surgeon general—requested in the aftermath of the Columbine High School tragedy—which drew on the expertise of violence researchers across the country. They point to clear changes in the way this country should handle the problem of youth violence.

"There are programs that are in fact effective in preventing youth violence—and it's really critical that those programs be implemented in a timely fashion," said Surgeon General David Satcher.

At the same time, "most of the things that people are out there doing in our communities and schools have never been evaluated," said Delbert Elliott, senior scientific editor of the surgeon general's report and director of the Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence at the University of Colorado at Boulder. "We simply don't know if they work or not."

That, he said, can translate to more than a waste of time, money and effort. Studies outlined in the surgeon general's report show that some popular measures—such as funneling juveniles into the adult criminal justice system, counseling youth in groups and prison visit shock programs like Scared Straight—may further harden troubled children and increase their involvement in crime and violence.

Meanwhile, studies are finding that programs that aid low-income pregnant mothers, help high risk children forge stronger ties to school and home and intervene on many fronts in the lives of delinquents can reduce the chances of later violence.

Yet for all the new knowledge, it's still impossible to predict if any one child will turn to violence, making "profiling" of high-risk children a potentially damaging game. Even risk factors with so-called "strong" effects—such as having delinquent friends—aren't good predictors. Most children who have been exposed to such risks won't become violent.

Moreover, researchers haven't found clear profiles for a youth who commits the rare kind of school violence seen in Santee's Santana High School and at Columbine, said Jane Grady, assistant director at the Colorado violence center.

For instance, a study by the U.S. Secret Service and Department of Education of 37 school shootings revealed that factors such as school performance, presence or absence of mental and drug problems and being a loner or being sociable varied greatly among different cases.

The report found, however, that such attacks are usually planned, that the perpetrators often have perceived grievances, that two-thirds believed they had been bullied or persecuted—and in more than three-fourths of the cases the attacker told at least one person (usually a peer) about his plans.

Thus, said Grady, it's really important that children learn that reporting such threats isn't "ratting" but crucial in keeping schools safe and getting the troubled youth help.

Long-Term Studies Focus on Violence

Much of the new information about violent and delinquent behavior has emerged from several large, long-term studies.

The power of such "longitudinal" studies is that they can track thousands of individual children's lives in detail, into adolescence and beyond, and watch how violent lives develop. Using statistical methods, researchers can figure out which factors in those children's lives seem to steer them toward deviance.

Clear patterns are emerging.

Violent careers develop along two main paths. Sometimes, children start early: They've already committed acts of violence before puberty. Early starters are more likely to become chronic, violent offenders. More commonly, children who turn to violence do so first in adolescence.

Myriad risk factors exist for later violence, including birth complications, poverty, antisocial parents, poor parenting, aggression, academic failure, psychological problems and alienation from home, school and non-delinquent peers.

Some risk factors have more clout than others. And their importance waxes and wanes through a child's life.

For instance, a young child's life is centered in the home, and thus it's not surprising that a poor home life in the early years of life is particularly damaging. But hanging with antisocial peers is only a weak risk factor until children hit adolescence and are straining to join the wider world. Then it becomes a huge influence.

As factors pile up, so does risk. For instance, low-level brain damage sustained in utero from a mother's drinking or smoking paired with harsh parenting "combine viciously" to increase the risk for later violence, said David Olds, professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver.

And scientists in one study estimated that a 10-year-old child exposed to six or more different risk factors was 10 times more likely to commit violence by age 18 than a child with only one.

Some risk factors are weaker than might be expected, such as the effect of watching violence on TV.

TV violence has a larger effect on aggressive behavior and attitudes than on actual, physical violence, research has found. Many people have aggressive personalities that serve them well on the tennis court or in the boardroom, but they don't resort to killing and maiming.

The link between violent TV and actual violent acts, while statistically significant, is small, according to studies.

This doesn't mean that media violence should be ignored, Elliott said, just kept in perspective.

Biological traits that might render some more prone to violence also weren't emphasized in the surgeon general's report—because the data, said Elliot, are too preliminary. Some scientists believe the report should have said more on this topic.

"Biology is half of the equation," insisted Adrian Raine, Robert G. Wright professor of psychology at USC.

For instance, Raine said, studies show that certain children are at heightened risk for later delinquent behavior: ones whose heart rate, sweat rate and brain activity are lower than those of other children.

Perhaps, Raine said, these youngsters seek excitement to get their metabolisms into a more comfortable, aroused state. Or perhaps such "cool cucumbers" are less fearful than other children.

"If you're lacking in fear, you're less bothered about getting into a fight and getting your nose broken," Raine said.

Raine's group has also scanned the brains of murderers and found they have less activity in a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex—an area involved in impulse control.

Yet studying nature, just like nurture, hasn't produced definitive predictors of violence: a few years ago Raine had his own brain scanned and found it looked rather like a murderer's.

"I've never been convicted of a homicide!" he insisted. The point, he added, is while factors like brain imaging can provide important clues, "single measures—whether biological or social—will never by themselves predict violence."

Results of Reducing Risk

It's one thing to talk about risk factors. It's another to show that a given risk factor actually causes violence. But one way to test whether a risk factor is causal is to try to reduce that risk among subjects in scientifically controlled studies and then look, years later, to see if the result was less violence.

Such studies are pointing toward strategies that seem to work. In one program, Olds and co-workers provided nurses' home visits for low-income, first-time pregnant mothers. The girls were helped to better manage their pregnancies as well as care better for their babies and plan for the future.

The program thus tackled several areas of risk. It reduced the chances of fetal brain damage from the mother's smoking and drinking and improved the mother's parental skills and home life. By age 15, the children whose moms had gotten the intervention had a 50% lower arrest rate.

Olds' group is now helping sites across the country—including ones in Los Angeles—set up similar programs.

Another effective program targeting children in high crime neighborhoods was developed by David Hawkins, director of the Social Development Research Group at the University of Washington in Seattle. The researchers helped teachers and parents increase elementary children's bonding to school and family by, for instance, guiding the adults to give the children more responsibilities in the home and classroom, and consistently praising them for good work.

"We all want to be bonded. We all want to be part of a group—that's part of the human condition," Hawkins said. "If we don't create the bonds we want, then they're going to be available elsewhere"—perhaps in a bad place, like a gang.

Hawkins' intervention made a difference: 60% of the high-risk children who didn't receive the intervention had been violent by age 18 compared with 48% of those who were helped.

There are other effective programs tackling children who have already gotten into trouble—such as one known as "multi-systemic therapy," which uses behavioral treatment in a full court press on all aspects of delinquent children's lives, including family, school, neighborhood and friends. In controlled trials, it cut rates of repeat offenses by 25% to 70% compared with rates for children who didn't receive it, at less than one-fourth the cost of an eight-month stay in a juvenile correctional facility.

But other interventions don't work as well.

Conventional psychotherapy and counseling often carry little clout, studies show—at least in reducing violence. Behavior management and skill-building approaches are much more useful.

School-visiting programs like DARE (in which students are warned against drug use, a risk factor for violence) also don't seem to work, according to many studies and evaluations. These reveal that children who go through DARE are just as likely to use drugs as those who don't. Researchers suggest that DARE is ineffective because it's implemented at the wrong age—in grades 5 and 6—before peer pressure kicks in with a vengeance. Nor does it teach children how to resist that pressure.

Those criticisms are unfair, countered Dr. Herbert Kleber, head of the science advisory board for DARE and an addiction researcher at Columbia University: "Most of the evaluations have been so flawed that it is hard to draw conclusions from them," he said.

A revamped program—aimed at middle and high school as well as younger children—is now being tested. It includes more skill-building to help youths deal with challenges like peer pressure.

Other studies have found that juvenile boot camps, moving children into the adult justice system and shock programs like Scared Straight (where delinquent children are given graphic descriptions of prison life by jail inmates) are similarly ineffective.

In fact, these and other strategies may even increase rates of delinquency, researchers say.

Studies, for instance, have shown higher rates of recidivism among children who were moved into the adult criminal justice system: 30% vs. 19% (with a shorter time to rearrest) in a Florida study of 5,000 juveniles; 58% versus 42% within two years in a Minnesota study; similar results in studies in Pennsylvania and New York.

"Kinder" interventions can backfire too. A University of Oregon study showed that high-risk adolescents who met regularly in a group for behavioral therapy were more likely to get into trouble in the following years—to smoke, cause problems in school and even resort to violence—than a group of similar children who never met each other.

The likely cause: children reinforcing their own and others' bad behavior.

Studies also show that street workers who visit gang members and try to straighten out their lives can actually increase cohesiveness of the gangs, said Malcolm Klein, emeritus professor at USC and a longtime gang researcher.

But gang street workers don't believe their intervention does harm.

"In some extreme cases there may be some validity to it, but it's not the norm," objected Henry Toscano, chairman of the Assn. of Community Based Gang Intervention Workers.

And many people in the criminal justice system support boot camps, scare programs and "adult time."

True, youths who are tried as adults may go on to commit offenses more often—but that's because those children were the most hard-bitten offenders to begin with, said David LaBahn, deputy executive director of the California District Attorneys Assn. in Sacramento.

And Scared Straight programs may well turn a youth around if delivered at the right time in that child's life, said LaBahn. Studies could easily miss the good that's done, he said, if it is swamped by negative results from other children who aren't ready to hear the message.

Overlooking Root Causes

Some social scientists say that even proven interventions miss the main point of what is causing high rates of violence in our society.

"We have a horrible problem that dwarfs what is seen in other advanced countries," said Elliott Currie, a sociologist who teaches in the legal studies program at UC Berkeley. If we really want to make a difference, he said, we should tackle—nationwide—problems like poverty, health care and child care. But failing a major societal overhaul, at least officials should implement programs that work, violence researchers say.

"So much of what people do is driven by past practice, by what people are comfortable with, by the political winds," said Terence Thornberry, professor in the school of criminal justice at the State University of New York at Albany.

"How do we move policymakers away from what they may be comfortable with and toward systematically implementing programs with effectiveness? We haven't by any stretch of the imagination crossed that bridge yet."

Reading the Risk

Researchers have identified many factors that may add up in a child's life and increase the risk for violent behavior. The factors have different srengths and appear more influential at some stages of childhood than at others.

|

EARLY RISK FACTORS Strong Effect Moderate Effect Weaker Effect |

LATE RISK FACTORS Strong Effect Moderate Effect Weaker Effect |

Source: "Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General"

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

Cho a typical shooter

From the LA Times:

Va. Tech Shooter a 'Textbook Killer'

By MATT APUZZO and SHARON COHEN, Associated Press Writers

9:35 PM PDT, April 19, 2007

BLACKSBURG, Va. — In high school, Cho Seung-Hui almost never opened his mouth. When he finally did, his classmates laughed, pointed at him and said: "Go back to China."

As such details of the Virginia Tech shooter's life come out, and experts pore over his sick and twisted writings and his videotaped rant, it is becoming increasingly clear that Cho was almost a textbook case of a school shooter: a painfully awkward, picked-on young man who lashed out with methodical fury at a world he believed was out to get him.

"In virtually every regard, Cho is prototypical of mass killers that I've studied in the past 25 years," said Northeastern University criminal justice professor James Alan Fox, co-author of 16 books on crime. "That doesn't mean, however, that one could have predicted his rampage."

When criminologists and psychologists look at mass murders, Cho fits the themes they see repeatedly: a friendless figure, someone who has been bullied, someone who blames others and is bent on revenge, a careful planner, a male. And someone who sent up warning signs with his strange behavior long in advance.

Among other things, the 23-year-old South Korean immigrant was sent to a psychiatric hospital and pronounced an imminent danger to himself. He was accused of stalking two women and photographing female students in class with his cell phone. And his violence-filled writings were so disturbing he was removed from one class, and professors begged him to get counseling. He rarely looked anyone in the eye and did not even talk to his own roommates.

Cho, who killed 32 people and committed suicide at the Blacksburg campus Monday, cast himself in his video diatribe as a persecuted figure like Jesus Christ. Cho, who came to the U.S. at about age 8 in 1992 and whose parents worked at a dry cleaners in suburban Washington, also ranted against rich "brats" with Mercedes, gold necklaces, cognac and trust funds.

Classmates in Virginia, where Cho grew up, said he was teased and picked on, apparently because of shyness and his strange, mumbly way of speaking.

Once, in English class at Westfield High School in Chantilly, Va., when the teacher had the students read aloud, Cho looked down when it was his turn, said Chris Davids, a Virginia Tech senior and high school classmate. After the teacher threatened him with an F for participation, Cho began reading in a strange, deep voice that sounded "like he had something in his mouth," Davids said.

"The whole class started laughing and pointing and saying, `Go back to China,'" Davids said.

Stephanie Roberts, 22, a classmate of Cho's at Westfield High, said she never witnessed anyone picking on Cho in high school. But she said friends of hers who went to middle school with him told her they recalled him getting bullied there.

"There were just some people who were really mean to him and they would push him down and laugh at him," Roberts said. "He didn't speak English really well and they would really make fun of him."

Cho's great aunt, who lives in South Korea, said Thursday that because he did not speak much as a child and after the family emigrated to the United States, doctors thought he may be autistic.

"Normally sons and mothers talk. There was none of that for them. He was very cold," Kim Yang-soon said in an interview with AP Television News. "When they went to the United States, they told them it was autism."

Neither school officials, who have his educational records, nor police who have his medical records, have mentioned such a diagnosis this week. Autistic individuals often have difficulty communicating, but such a diagnosis would not necessarily explain his violence.

Regan Wilder, 21, who attended Virginia Tech, high school and middle school with Cho, said she was sure Cho probably was picked on in middle school, but so was everyone else. And it didn't seem as if English was the problem for him, she said. If he didn't speak English well, there were several other Korean students he could have reached out to for friendship, but he didn't.

About the only difference between Cho and a typical shooter is that Cho wasn't a white boy. But he was Asian, a "model minority." He was under intense pressure to be popular and successful just like his white peers.

And the winner is...

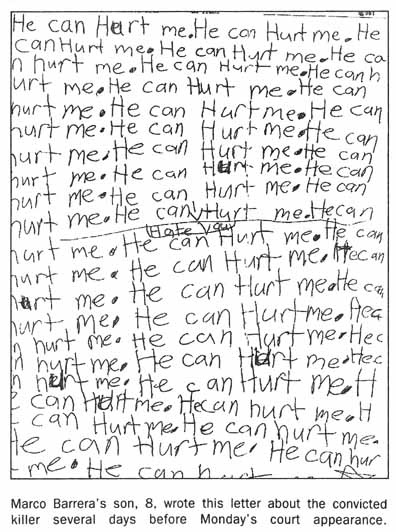

Which risk factors are most important in causing shooting rampages? From a letter to the LA Times, 3/24/01:

[I]n less than a month another high school shooting rampage has devastated yet another group of students and parents. And in less than a month yet another round of righteous finger-pointing and bleating defenses will begin: It's not guns....It's not violent entertainment....It's not bullying and social cliques....It's not parents....

The list goes on ad nauseam. Perhaps now, people will finally consider the notion that all these influences combined finally push some kids over the edge. It's time to clean house, not just one room.

DAVID KOPF

Aliso Viejo

Is that your final answer? Yes, we have a winner. Ding-ding-ding!

As Kopf so rightly says, the solution is to tackle the cultural bias, the guns, and the media simultaneously. Pick your target, take aim, and fire (and note the violent imagery we use routinely). Stop denying the problems and start solving them.

And note the recommendation of one expert quoted in Mestel's article:

So the solution is to implement specific programs that work to handle particular kids at risk. And to address societal problems in general to change our cultural expectations. In other words, the solution is to implement the Democratic Party agenda, since that's what Democrats call for. (In terms of government, the answer is to rightsize it, not upsize or downsize it.)

Don't ignore the media

I'm tempted to highlight all the factors the media can contribute to. Among them are delinquency, antisocial behavior, and aggression. The direct harm caused by media violence isn't the only influence we may attribute to the media, by far.

To summarize the articles' conclusions: Forget silly conservative "solutions" like "family values," "just say no," or posting the Ten Commandments. Try real solutions like those advocated by the people who have studied the problem. But don't just throw money or resources at troubled youths. Use targeted government programs that have proved to be effective.

Even if we focus on broad problems like poverty, let's not ignore the role of cultural values. Other countries have much more poverty but much less violence. Our culture not only tolerates poverty and poor health care, it encourages high expectations. Americans have a sense of entitlement: work hard, play fair, and we shall achieve the American Dream.

And when that doesn't happen, as it often doesn't, we don't do as other cultures do. We don't wrap people in a warm cocoon of compassion and community. We tell people they're losers who didn't try hard enough. We leave them at home with a gun and a training manual (aka a violent movie, video game, or PUNISHER comic) and tell them to solve their own problems.

Guess what solutions they come up with? Check your local listings for the next shooting by a distraught student, boyfriend, postal worker, day trader, or white supremacist. Film and hand-wringing at 11.

As I've said many times, media violence generally doesn't cause real violence. Nor does the availability of guns. Not directly, anyway. What these conditions do is fuel the violent rage so evident in our culture. The violent rage that comes from living in a society that advocates the American Dream but doesn't deliver it.

Media violence and guns contribute to the problem, in other words, not to the solution. As part of the problem, they deserve our attention along with the inadequate social programs. Again, we have a good idea what works, if only we commit ourselves to doing it.

Along with these particular problems, our overall cultural mindset also deserves attention. As noted above, weak social ties and antisocial behavior are strong indicators of trouble. Our culture lacks human bonds because it emphasizes the individual as solitary gunslinger and society as a hostile frontier.

This mindset is a much tougher nut to crack, but it's not impossible. Change can happen easily sometimes, even on a national scale. If Nazi Germany, imperial Japan, communist Russia and Eastern Europe, apartheid South Africa, and autocratic Mexico can transform themselves in a single generation, so can the United States.

Related links

Doing nothing is a copout

Violence in America

America's cultural mindset

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.