An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Windtalkers: No Guts, No Glory:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Windtalkers: No Guts, No Glory: An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Windtalkers: No Guts, No Glory:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Windtalkers: No Guts, No Glory:

Windtalkers is arguably the biggest Native-themed movie since Smoke Signals, which was arguably the biggest since Pocahontas. But critics are saying it's something of a bomb—and they don't mean "da bomb." Some comments suggest the movie's problems:

Overall reactions

It's official.

Windtalkers, the MGM release which features Canadian Native actor Adam Beach and Navajo newcomer Roger Willie as Navajo Code Talkers, sucks.

Well, that's according to almost every single film critic on the face of the earth. Except Natasha Washington of The Daily Oklahoman. She found the movie could be "one of the best portrayals of World War II to hit the screen."

But she added: "You be the judge."

Other reviewers appear to have taken up the advice and gone further. They weren't just the judge, they were the jury and executioner.

Indianz.com, 'Windtalkers' Largely a Bust, 6/14/02

"Windtalkers," the story of American Indians recruited as Marines and trained to use their language as code during World War II, feels about 40 years old, with its faded colors and bombastic, horn-heavy score.

Christy Lemire, "'Windtalkers' Leaves Plot Blowing in the Breeze," Associated Press, 6/13/02

[W]ith a weak script that makes one think that the screenwriters never read the great war books of James Jones and Norman Mailer, the characters don't have near the dimensionality required to help the movie soar above the usual bloody Hollywood balderdash.

David Hunter, "Windtalkers," Hollywood Reporter, 6/6/02

Crack the code behind Windtalkers, and you'll find it's just another cookie-cutter war flick, complete with stereotypical characters, overblown battlefield sentimentality and deafening explosions.

E! Online

Pretty much everything that could misfire and accentuate the disillusioning does go kerplop in the course of "Windtalkers."

One character gets to observe, "You're a mess, Joe." It would have been advisable to take this remark seriously before entrusting an entire war epic to the wrong protagonist.

Gary Arnold, "'Windtalkers' Message Is Garbled," Washington Times, 6/14/02

I don't think there's ever been such a failure of imagination going from the idea to what ended up on screen.

Sherman Alexie

Historical accuracy

"I liked it," said [78-year-old codetalker Bill] Toledo, a man of few words. But not so much for its historical accuracy or realism, he said. There was little of that.

Jessica Delos Reyes, "Code of Honor," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

No one in Hollywood has time for a history lesson when there's stuff to blow up.

Jeff Strickler, "John Woo Spins an Action-Packed Tale with 'Windtalkers'," Minneapolis Star Tribune, 6/14/02

The movie about Navajo Code Talkers doesn't live up to its hype. "Windtalkers" is a historical train wreck.

Jessica Delos Reyes, "'Windtalkers' Full of Hot Air," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

Native themes

There's a great movie waiting in the story of the Navajo code talkers of World War II.

With patriotism and sacrifice, they used a code based on their difficult language to help the U.S. military keep crucial battle information secret from the Japanese.

But "Windtalkers" isn't that movie.

Steven Rosen, "A Mere Whisper," Denver Post, 6/14/02

Chief among the complaints is the portrayal of the Code Talkers. MGM pitched the project as as educational vehicle but moviegoers won't learn much about the men who helped win World War II, according to the critics.

Indianz.com, 'Windtalkers' Largely a Bust, 6/14/02

The possibilities here are obviously rich; the subject breathes with historical depths and irony, and it seems ripe stuff for a whole generic re-examination of both the American Western and war film genres. But "Windtalkers" doesn't really delve deeply into psychology or American and Navajo culture.

Michael Wilmington, "Movie Review, 'Windtalkers'," Chicago Tribune, 6/14/02

"Windtalkers" isn't daring enough to concentrate on the work demanded of its fictionalized set of code talkers, Adam Beach as Ben Yahzee and Roger Willie as Charlie Whitehorse, or even on the culture shock they might experience when transported from the U.S. Southwest to boot camp and then the South Pacific.

Gary Arnold, "'Windtalkers' Message Is Garbled," Washington Times, 6/14/02

While the film does not unduly wallow in patriotism, it offers little more than thumbnail sketches of characters and shies away from the ugly language and attitudes that were part of the times.

The issue of prejudice in the squad is thinly covered with the character of a dopey Texan (Noah Emmerich).

David Hunter, "Windtalkers," Hollywood Reporter, 6/6/02

"Windtalkers" has its own Navajo problem because it gives short shrift to the real dilemma: imagine becoming an elite marine during World War II only to be baby-sat. "Windtalkers" invents an angle — kill the Navajos if necessary to prevent their capture, an act not known to have happened — and ignores the more compelling truth, that the Navajos are prevented from being front-line troops in the same war in which a Native American helped raised the flag at Okinawa. How do you prove you're a patriot if you're treated like a second-class citizen?

Given the knee-jerk patriotism of recent war movies, it's discouraging to see "Windtalkers" evade pertinent facts that could have recast the doubled-edged issues of racism and loyalty and made them relevant to contemporary times.

Elvis Mitchell, "Of Duty, Friendship and a Navajo Dilemma," New York Times, 6/14/02

"Windtalkers" comes advertised as the saga of how Navajo Indians used their language to create an unbreakable code that helped win World War II in the Pacific. That's a fascinating, little-known story and might have made a good movie. Alas, the filmmakers have buried it beneath battlefield cliches, while centering the story on a white character played by Nicolas Cage. I was reminded of "Glory," the story of heroic African-American troops in the Civil War, which was seen through the eyes of their white commanding officer. Why does Hollywood find it impossible to trust minority groups with their own stories?

There is a way to make a good movie like "Windtalkers," and that's to go the indie route. A low-budget Sundance-style picture would focus on the Navajo characters, their personalities and issues. The moment you decide to make "Windtalkers" a big-budget action movie with a major star and lots of explosions, flying bodies and stunt men, you give up any possibility that it can succeed on a human scale. The Navajo code talkers have waited a long time to have their story told. Too bad it appears here merely as a gimmick in an action picture.

Roger Ebert, "Windtalkers," Chicago Sun-Times, 6/14/02

The basic premise

Picky WWII buffs may call foul here and there. The whole imperative of the film — that we could lose the war if the Navajo is captured — is basically false, given that Japan was on its knees in late 1944, and Saipan already was won when most of the film's action takes place.

William Arnold, "'Windtalkers' Breezes Past Inaccuracies," Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 6/14/02

Considering that the movie is called "Windtalkers," the Navajos don't speak in code that often. They communicate in their language over crackly radio transmissions, with English subtitles, but there is no crucial moment in which the code comes into play. So the early scenes in which they learn to use their words secretly seem like wasted exposition.

Christy Lemire, "'Windtalkers' Leaves Plot Blowing in the Breeze," Associated Press, 6/13/02

The point of the movie is that the Navajos are able to use their code in order to radio information, call in strikes and allow secret communication. In the real war, I imagine, this skill was most useful in long-range strategic radio communication. "Windtalkers" devotes minimal time to the code talkers, however, and when they do talk, it's to phone in coordinates for an air strike against big Japanese guns. Since these guns cannot be moved before airplanes arrive, a call in English would have had about the same effect. That Woo shows the Windtalkers in the heat of battle is explained, I think, because he wants to show everything in the heat of battle. The wisdom of assigning two precious code talkers to a small group of front-line soldiers in a deadly hand-to-hand fight situation seems questionable, considering there are only 400 Navajos in the Pacific theater.

Roger Ebert, "Windtalkers," Chicago Sun-Times, 6/14/02

[T]he recon team is caught in a fire zone, their radio damaged by shrapnel. Yazhee has an idea: With his darker skin, he thinks he could pass for Japanese. He offers to sneak behind enemy lines and steal one of their radios. Enders approves the idea.

Let's review: You're supposed to kill Yazhee rather than let him get close to the enemy, but you're willing to let him stroll into a Japanese camp even though he doesn't speak a word of their language and doesn't look remotely Japanese except to a bunch of white guys who can't tell one dark skin from another. Sure, that makes sense.

Jeff Strickler, "John Woo Spins an Action-Packed Tale with 'Windtalkers'," Minneapolis Star Tribune, 6/14/02

Protect the code, kill the codetalker?

A bogus suspense element — the bodyguards have been instructed to protect "the code" at all costs, implying sacrifice of the code talkers in dire situations — never makes a particle of sense. It would more than suffice if the Navajo characters were just keenly aware of the perils that exist on a battlefield.

Gary Arnold, "'Windtalkers' Message Is Garbled," Washington Times, 6/14/02

[I]s the film's whole "moral dilemma" merely bogus melodrama? According to the film's production notes, some real-life code-talkers did have bodyguards lest other soldiers confuse their physical features with the Japanese. (The film incorporates such an incident, a far-fetched but cinematically rousing one reminiscent of Woo's Hong Kong movies with their elaborately orchestrated scenes of violence, involving Beach and Cage.)

But the production notes also state that Marine Corps historians found no evidence any such kill-to-prevent-capture orders were given. "It would be illegal for a Marine to be ordered to kill a fellow Marine," it says.

Steven Rosen, "A Mere Whisper," Denver Post, 6/14/02

There is substantial controversy about whether this policy to kill codetalkers in danger of capture in fact existed. The Marine Corps flatly denies it. Codetalkers interviewed for a History Channel documentary differed among themselves, and skepticism ranged all the way to one man who claimed he didn't even have a bodyguard. When I spoke to Samuel Smith, one of the original 29 codetalkers who devised the code, he told me that some of them were assigned bodyguards only after a codetalker was taken POW by American forces. It seems the bodyguards were deemed necessary to protect the codetalkers from their own troops, before some Diné got wasted rather than captured.

Smith explained, without rancor, that in the island-hopping campaign there were often no fixed lines. The Japanese often popped up from behind. Most of the white folks who manned the frontline combat units had never seen a fullblood Indian, and the Diné did, he supposed, look a bit like Japanese.

Steve Russell, Windtalkers—A Review, IMDiversity.com, 6/21/02

Cage was ordered to protect the code—not the Code Talker—at any cost.

"Hollywood people wanted it that way," said Toledo. "No Code Talkers were captured, not like in the movie."

It is true, however, that Toledo was assigned a bodyguard. But the bodyguard's job was not to protect him from the enemy, but from the white men in his own outfit. After Toledo was mistaken for a Japanese soldier, Sgt. Richard Bonham was assigned to protect him.

As for assassinating Toledo if he fell into enemy hands as Cage is ordered to do in the film, Bonham calls this ridiculous.

"Whoever thought that up must be off their rocker," he said.

"That would have been murder on my part. I would have been court-martialed, disgraced; I couldn't have done it."

Jessica Delos Reyes, "Code of Honor," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

While the military officially denied there were any orders to kill fellow Marines, producers Alison Rosenzweig and Tracie Graham insist the storyline was based on interviews with some of the original 29 Code Talkers, including Carl Gorman, who confirmed the story. They also point out that the Marines approved the final script.

Valerie Taliman, Windtalkers Promotes Respect for Navajo, Indian Country Today, 6/14/02

The Codetalkers Association, Smith told me, had a debate about the movie centering on whether they should make a major push for the truth. They decided not. They decided that the white guys wanted to make a film to make money and they knew how to make up a story to accomplish that because they are professionals. The codetalkers decided that as long as the treatment of their role was respectful, they would not squawk about historical accuracy. They understand that making up heroic stories about people is an honoring custom in many cultures, but they would like the truth to be told some day.

Steve Russell, Windtalkers—A Review, IMDiversity.com, 6/21/02

War cliches

Here's a not-so-divine secret of the ya-ya brotherhood: We boys like war movies.

We like it when stuff gets blown up, enemies get mowed down by heroes with tommy guns, and at the end, that's our flag flying up there. I don't know, it's just so . . . cool. So sue us.

And here's the warriest of all war movies to come along since "Saving Private Ryan," called "Windtalkers," John Woo's story of the not-famous-enough Navajo combat encoders. It's like one of those big '50s jobs with huge battle scenes, emotions painted in bold primaries (love! loyalty! sadness!), a core of truth and heroism, and a kind of technicolor grandeur.

So why don't we like it so much?

The answer is that despite a cast of thousands, a budget estimated at $118 million, and a re-creation of the Pacific battles that rivals any before, the movie's stylizations – for which, of course, Woo is justly famous and without which he could not or would not have made the film – seem singularly wrong.

I am always amazed at actual combat footage: The soldiers appear so informal and undramatic. They never seem to be in any heroic poses; their minds, if you can infer from their body postures, are concerned with very small things, like "Let's get over there" or "Let's get down" or "Gosh, I wish I wasn't here." They are beyond rhetoric or exhortation. They look sad and weary, not charged with blood lust. They look like the homeless, and in a sense they are, for whoever would be at home on a battlefield?

That's not how Woo sees war. For him it's almost an opera, declamatory and dramatic, and the body language has more to do with dance than actuality. It's highly theatricalized and to a certain extent martial-articized.

Stephen Hunter, "'Windtalkers': John Woo's Pacific Theater," Washington Post, 6/14/02

It has no shortage of violent situations, but "Windtalkers" also seems to have its eye on being thoughtful and character-driven, but Woo doesn't have the best touch for this, and Rice-Batteer's standard-issue war movie script isn't any help. Throwing in everything except someone pulling the pin from a grenade with his teeth, "Windtalkers" seems to have ransacked every old World War II movie for overly familiar material. There's the guy who plays the harmonica, the guy who gives the "if anything should happen to me" speech, even the bigoted guy who sees the error of his ways once a Navajo saves his life. When it comes to learning experiences, it's hard to beat a really good war.

Kenneth Turan, "Unable to Crack the Code," Los Angeles Times, 6/14/02

This is a chapter of history not widely known, and for that reason alone the film is useful. But the director, Hong Kong action expert John Woo, has less interest in the story than in the pyrotechnics, and we get way, way, way too much footage of bloody battle scenes, intercut with thin dialogue scenes that rely on exhausted formulas. We know almost without asking, for example, that one of the white soldiers will be a racist, that another will be a by-the-books commanding officer, that there will be a plucky nurse who believes in the Cage character, and a scene in which a Navajo saves the life of the man who hates him. Henderson and Whitehorse perform duets for the harmonica and Navajo flute, a nice idea, but their characters are so sketchy it doesn't mean much.

Roger Ebert, "Windtalkers," Chicago Sun-Times, 6/14/02

There are the usual war movie cliches; you know that when a soldier takes off his wedding band and hands it to the guy sitting next to him in the trench — to give to his wife in case something, you know, happens to him — that it's only a matter of time before something, you know, happens to him.

And there is the obligatory (yet totally unnecessary) romance between Enders and Rita (Frances O'Connor), a nurse who helps him recover from an injury early in the film. O'Connor plays a role similar to Kate Beckinsale's last year in "Pearl Harbor."

Christy Lemire, "'Windtalkers' Leaves Plot Blowing in the Breeze," Associated Press, 6/13/02

Joe's brooding hostility stymies Ben's friendly overtures, obviously setting us up for a change of heart somewhere down the line.

The problem is that bringing Joe around obliges us to humor Mr. Cage as a fighting machine so obsessive that he's awarded his very own banzai and turkey-shoot interludes. I don't think any actor in Hollywood history has killed as many make-believe Japanese soldiers at such point-blank range. On one lunatic occasion, it even amuses the filmmakers to have Joe and Ben masquerade as Japanese soldiers, a pretext that would play better as a bloodless escapade with Abbott and Costello.

Gary Arnold, "'Windtalkers' Message Is Garbled," Washington Times, 6/14/02

[H]is hand-to-hand combatants mow each other down gangster-style, fly through the air and explode into flame like ciphers in a Spaghetti Western, and even, at one point, manage to get into a Hong Kong standoff: each with a barrel to the other's forehead.

William Arnold, "'Windtalkers' Breezes Past Inaccuracies," Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 6/14/02

Native stereotypes

We see cinematographer Jeffrey Kimball's panoramic shots of Monument Valley's splendor, home to so many John Ford westerns, and then a group of Navajo waiting for the Greyhound to take soldiers to war.

It's such a nice mix of the old and young, the mysterious and the technologically advanced, the insular and the expansive. It's the visual equivalent, in some ways, to the fascinating decision by the military to use the Navajo language as a basis for a secret code and then work with that community to train and use code talkers.

Steven Rosen, "A Mere Whisper," Denver Post, 6/14/02

Another problem I had was with the opening and closing scenes of the movie. Monument Valley once again served as the stereotypical location for the Navajos.

The whole "hanging-out-on-the-cliffs-of-a-mesa-with-turquoise" scene has been overused.

Levi J. Long, "'Windtalkers': It's Not What Grandpa Lived," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

This movie, which is supposed to chronicle Native Americans' contributions to the war effort, instead focuses on a white man. This was supposed to be the story of the Code Talkers, not of the big-name white actor struggling with a scenario that never really existed.

Jessica Delos Reyes, "'Windtalkers' Full of Hot Air," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

The main complaint I've heard is the casting of a non-Navajo actor, Adam Beach, as Pvt. Ben Yahzee. People often ask why a Navajo actor wasn't cast.

Perhaps it is the small pool of talented actors; there wasn't a wide range of choices available....I'm just grateful that Lou Diamond Phillips wasn't given the role.

Levi J. Long, "'Windtalkers': It's Not What Grandpa Lived," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

The Indians are seen one-dimensionally as really nice guys.

Roger Ebert, "Windtalkers," Chicago Sun-Times, 6/14/02

[T]hese talented Native American actors succumb to native stereotypes: the strong, silent type, or the happy philosophical type. Neither really demonstrates too much emotional depth, but perhaps not by their own fault.

Jessica Delos Reyes, "'Windtalkers' Full of Hot Air," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

Beach could have spent more time practicing his lines. In order to correctly enunciate Navajo, a person needs years of practice to get it just right.

Levi J. Long, "'Windtalkers': It's Not What Grandpa Lived," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

I can't imagine any Navajo out there who didn't grimace at the spelling of the name Yahzee. I assume this was done so that non-Navajo audiences could easily pronounce the name. But audiences aren't as dumb as Hollywood thinks.

[B]y the way, it's spelled Yazzie.

Levi J. Long, "'Windtalkers': It's Not What Grandpa Lived," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

The movie is bloody but weirdly beautiful, sometimes along what seems like naively stereotypical lines. Everyone knows Indians are knife fighters, right? So when the Japanese close in on Yahzee or his close friend Charlie Whitehorse, each private pulls an Indian knife – the deer foot as grip, available in the Wisconsin Dells or on the Internet for only $12.95 – from his buckskin boot sheath and dances with blades, as they whirl and dodge and slice and spin. I cannot say the primitive kid who will not leave my head didn't like this stuff; at the same time I cannot say the occasional grown-up who occupies the same space believed it for a second.

Stephen Hunter, "'Windtalkers': John Woo's Pacific Theater," Washington Post, 6/14/02

Embittered after realizing the true nature of Enders's assignment (he had truly respected and adored the sergeant), he becomes a killing machine without mercy and without fear. It's as if his death wish is now bigger than Joe's and that's what draws Joe back from the edge.

Stephen Hunter, "'Windtalkers': John Woo's Pacific Theater," Washington Post, 6/14/02

Samuel Smith does not begrudge Hollywood its liberties with history nor Nicholas Cage his central role in the film. Smith does strongly object to the title, "Windtalkers," claiming that it signifies persons who say much of little import.

Steve Russell, Windtalkers—A Review, IMDiversity.com, 6/21/02

Asian stereotypes

Although Woo is Asian, he treats the enemy Japanese troops as pop-up targets, a faceless horde of screaming maniacs who run headlong into withering fire.

Roger Ebert, "Windtalkers," Chicago Sun-Times, 6/14/02

The Japanese characters are a faceless enemy; no more than targets for the U.S. soldiers. They stand. They scream. And they're shot. Almost makes you feel sorry for them.

Jessica Delos Reyes, "'Windtalkers' Full of Hot Air," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

Nice touches

As Ben, Adam Beach ("Smoke Signals") shows real matinee-idol potential. With his warm smile and easygoing sweetness, he makes Ben a calm and tranquil, yet involving and inspiring, figure.

He's the eye of this war-drenched film's storm, and he's likable every moment he's on screen.

Steven Rosen, "A Mere Whisper," Denver Post, 6/14/02

The two actors do a fine job of portraying traditional Navajo characteristics of dignity, tolerance and devotion to family.

Valerie Taliman, Windtalkers Promotes Respect for Navajo, Indian Country Today, 6/14/02

Speaking of clichés. When I was in the military, everybody wanted to call me "chief," something Ben Yahzee has to confront. (I also noticed in conversation with Samuel Smith that he related conversations in which white GIs called him "chief.") In this film, they call Whitehorse's name and some horse's patoot starts making horse noises. That kind of thing used to happen to me. This kind of treatment may be a war movie convention, but I would bet I am not the only Indian GI who finds it very familiar even today.

Steve Russell, Windtalkers—A Review, IMDiversity.com, 6/21/02

Woo also took on the touchy issue of racism that the Code Talkers experienced. In several scenes in the movie Navajo soldiers are told they are "slanty-eyed savages" and look just like the Japanese.

In fact, [codetalker] Chester Nez said a fellow Marine once held a gun to his forehead because he thought Nez was Japanese.

Valerie Taliman, Windtalkers Promotes Respect for Navajo, Indian Country Today, 6/14/02

Ben Yahzee, the movie character, wants to be a history teacher if he survives the war. Like the real codetalker I interviewed, he is matter-of-fact about the poor treatment his people have received at the hands of the United States. However, he is not fool enough to believe that life under Fascism would be better and he recognizes that white Americans, while they may not always be the best of neighbors, are still neighbors.

Steve Russell, Windtalkers—A Review, IMDiversity.com, 6/21/02

Native reactions

For Native people, especially the Dine (Navajo), the formulation of "Windtalkers" has been a touchy topic.

The Code Talkers are held in the highest esteem and with the utmost of pride among our people. These men aren't just veterans. They're a living, breathing example of what we are: Strong. Intelligent. Bold. And cool.

These courageous Dine knights have proved themselves, above and beyond the Marine mantra of semper if (always faithful).

Levi J. Long, "'Windtalkers': It's Not What Grandpa Lived," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

Watching the horrific images of war on screen, I could not help but think that from where we sat as Navajos, patriotism and allegiance to our nation extends well beyond the 200-year-old United States of America.

Navajo ties to this land go back centuries to Dine' creation stories that tell of our emergence from Ni'hima Nahas'dzan, our Mother Earth. Our songs, ceremonies and language are rooted in her sacred mountains, rivers and forests. Our prayers pay reverence to the land, the water, the air, and the sky.

How ironic then that our language, once beaten out of our elders in government boarding schools, was used to defend America.

It was a privilege and proud moment to sit with a real American hero as we watched Windtalkers on the big screen and by the film's end, I was in tears. Not because the hero dies, but because I finally realized what our Navajo soldiers had to go through to defend our homelands — again.

We all owe them great respect and gratitude.

Valerie Taliman, Windtalkers Promotes Respect for Navajo, Indian Country Today, 6/14/02

I went to see Windtalkers Friday. Very interesting. I found it a little too thin for my taste, but I enjoyed the performances of Beach and Willie—although I think the directing of their talents could have be a little better. I did like that they didn't make them too reactionary to the racism. I liked that Willie learned the Code quicker than Beach. Wanted to know more about their characters and families. Navajo friends wanted to hear more Navajo. I am far from fluent in Navajo, but I could actually pick out a few words of what was spoken. I don't think the Navajo attitudes toward dead bodies was covered very well. It almost looked like it was repulsion and fear rather than a religious belief.

It is so funny that, growing up, I learned about the Creeks, Choctaw and other Oklahoma tribes' code talkers but did not hear of the Navajos until the 1970s. We have a lot better opportunity to learn each others histories and ways from the '60s on than before.

Eulala McDowell Pegram, e-mail

We saw Windtalkers on Sunday. Lots of gore and guns. I felt that the Code Talker aspect was shadowed by the Hero aspect of Cage...and the knife fights were stereotypical...It wasn't a bad movie, but could have done much more.

Vicki Lockard, e-mail

So to Hollywood I say: Try again. As Native people, we know our untold history is far more interesting than anything that's been put on film.

Jessica Delos Reyes, "'Windtalkers' Full of Hot Air," Native Voice, June 19-23, 2002

What would a Diné filmmaker do with the blood memory of The Long Walk and the concentration camp at Bosque Redondo? Would he point out the irony in the treaty the Navajo had to sign that banned them from combat forever, a treaty the Navajo asked to be abrogated so they could fight for their homes after Pearl Harbor? How about the Diné sacred history that admonishes them to live in Dinetah, the area bordered by the four sacred mountains? One thing is certain: a Navajo telling of this story would center on the codetalkers and their world rather than the fictional conflicts of a white man under fictional orders.

Today, we honor the codetalkers with heroic stories. Someday, we will honor their memories with true stories.

Steve Russell, Windtalkers—A Review, IMDiversity.com, 6/21/02

The result

In the end, the false take on the Navajo code talkers—focusing on the two white male leads and ignoring the essence of the true story—has shown itself in the box office flop the movie has become. The American audience, diverse in its thinking and its taste, will no longer accept such "Hollywood myths."

The lesson for MGM, and any other studio that is looking to create positive box office return, is that "Windtalkers" is compelling evidence that promoting the white male as the focal point is not the way to tell every story.

Elizabeth R. Valenzuela, Ignoring True Story Doomed 'Windtalkers', Los Angeles Times, 7/1/02

Rob's comment

For links to most of these reviews, visit Indianz.com.

I haven't seen Windtalkers yet, but not seeing a movie has never stopped me from commenting before.

Confirming that the movie is about white stars and a couple "other guys" is the Windtalkers events calendar, which lists the media appearances leading up to the movie's premiere. A tally of these appearances:

Nicolas Cage: 7

Christian Slater: 5

Adam Beach: 2

Roger Willie: 0

Actual codetalkers: 0

Final score: Anglos 12, Natives 2. The "windtalkers" are outpublicized, 6 to 1, in a movie supposedly about them.

True, John Woo and Nicolas Cage spoke often about how the movie honors the codetalkers. And students who have never met an Indian—who think Indians are tomahawk-wielding savages in headdresses—"honor" them with their school mascots. To some of us, the parallels are clear.

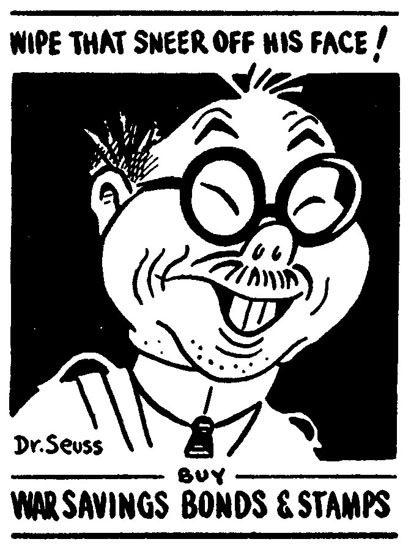

Subliminal message?

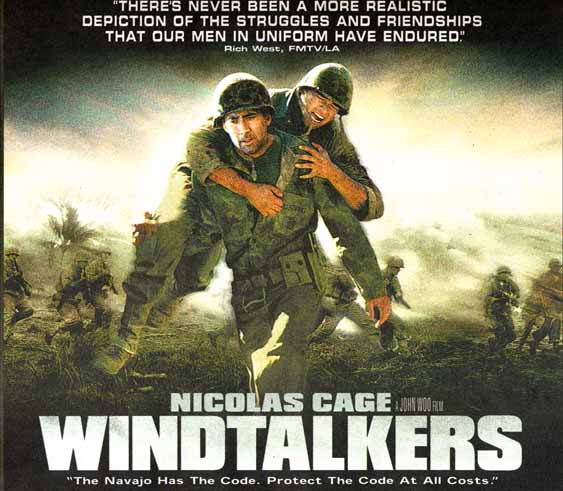

Another point worth mentioning is how the visuals reinforce the film's message. Consider the newspaper ads. In one, Nicolas Cage's steely gaze dominates. We expect this strong, silent American to triumph over evil just like John Wayne did.

Behind him is Adam Beach, supposedly the movie's raison d'etre. Beach is calling for help while he glances at Cage. It's clear whom the real hero is: the great white hope who will save the day.

Every detail in this ad confirms the message. Cage's heavily masculine face is prominent, while Beach's more delicate features are obscured. Cage's eyes are big and glaring; Beach's are shadowed slits. Beach's mouth is open and his fingers visible, creating a subtle aura of femininity. (Many cultures would consider that good, but not ours.)

Our mythology exalts the doer above the talker and so does this ad. Even the name "windtalker" (not codetalker, the proper term) suggests someone whose words are empty or full of hot air. Compared to Cage, Beach is "all talk"—an insult to most Americans. He's a counterpoint to the true hero: the stalwart man of action.

Even the actors' names fit their assigned roles. Cage, the seething cauldron of restrained righteousness. Beach, the harmonious complement to Nature's power. A person in a cage is someone who acts. A person on a beach is someone who is acted upon.

The message is even more explicit in another ad. Cage carries Beach from a war zone to safety. Cage has the same stony, implacable look, while Beach's eyes are shut and his mouth is gaping. He might be crying like a baby.

In our history books, saving and civilizing the world is America's duty. In this ad, Cage, the stoic adult, totes Beach, the mewling child, on his back. The Indian is literally the white man's burden.

So much for a century of progress, eh?

As for the movie's opening shot, it might've been interesting to start with a sweeping shot of Monument Valley...then sweep past it, past Shiprock, to some nondescript bus station in Gallup or wherever. That would allow the opening shot but make the point that it's hardly representative of the Navajo reservation. Paying homage to John Ford's stereotype of "foreign" Indian country isn't exactly a blessing.

Some Native viewers weren't too worried about historical accuracy. They were just glad to see themselves on the screen. This reflects the research showing that people don't want to be invisible, even if it means being misrepresented.

But there's some danger in this thinking. If Windtalkers does poorly—as it appears it will—a major studio may not make another codetalker movie for 50 years. One could argue that it's better to have no movie than a bad movie that ruins the market for Native subjects.

At best Windtalkers portrays Indians as Dances with Wolves did: positively but superficially. At worst it's another story of "exotic" Indians told from the white man's point of view. The definitive Native-themed movie remains to be made.

The real codetalker story (7/1/02)

Steve Russell adds his thoughts on what a real codetalkers story—a movie, novel, or comic book—might contain. Note the profound difference between a story told from the Anglo point of view and the Native point of view.

I am as we speak working on a more scholarly treatment of Windtalkers for Tulsa Law Review, and I find most of the literature to be anecdotal. It is obvious that the screenwriters mined the literature. Here are some anecdotes they got and some they didn't:

Anyway, Rob, there is a rich story mine left untouched by the movie because they choose to focus on the white guy.

That was practically no Indian POV except in conversations where Indian reality was conveyed to the white guys largely in one-liners. Yahzee mentions the Long Walk, being punished for speaking Navajo, fear of the dead....

The Navajo culture is an outsider view.

I imagine a Navajo telling would show the white world as the outsider view. How the Diné perceived Pearl Harbor as a danger to Dinetah. The difficulty having their hair cut, learning to eat when scheduled rather than when hungry and sleep when scheduled rather than when tired. How they detested the rations and invented ways to make do. (On one island, they served horsemeat to unwitting white guys who were also dying for fresh meat. The got past the rock hard cookies in their rations by heating them with the bacon and imagining fry bread. On another island, they killed a chicken with a homemade slingshot and make a stew...that had to be replicated many times for the white GIs.) During one desert survival training, the Diné took their water from cactus plants and came back with some water still in their canteens while some of the white squad went overboard in competing with them and wound up hospitalized for dehydration.

Because the Diné ceremonial cycle is so connected to Dinetah, the more traditional Navajos could never quite feel connected while overseas. The response to this was to either get home ASAP or never go home.

And from Steve's article for the Tulsa Law Review titled "Honor, Lone Wolf, and Talking to the Wind":

Because the story is focused on Nicholas Cage's character, those parts of the Navajo story that make it Navajo are related in one liners by Ben Yahzee, the movie character who wants to be a history teacher if he survives the war. He mentions The Long Walk, as the Dineh call their encounter with genocide, but one line does not communicate a blood memory of what it means to be Navajo any more than I could put a reader in Cherokee skin by uttering the phrase "Trail of Tears."

Yahzee mentions in passing that Navajos were punished in boarding schools for expressions of their culture, but this does not tell us how that culture prepared the code talkers for their role with songs and prayers that are difficult feats of memory work, much more difficult than the World War II code. We are never made aware that many code talkers are still alive today even with diminished life expectancies for American Indians because so many of them were in fact underage when they enlisted, a deception that was facilitated by the lack of written birth records on the reservation. The irony of the code talkers training on state-of-the-art communications gear and then returning to a reservation with no electricity is unexplored, as is the national disgrace of the death rate on that reservation from "inanition"—medical jargon for starvation. The long delay in recognition of the code talkers is at least understandable because their mission remained classified for years after the war.

Sadly (for MGM), Windtalkers seems to be tanking at the box office. Is that just a coincidence? No, I don't think so. As I and others have noted, Multiculturalism Sells! in this new millennium.

MGM didn't "get it," but the Native version is far more interesting than watching Nicolas Cage grunt and grimace through another heavyhanded performance. This is a story that deserves to be told the right way.

More information on the codetalkers

The Navajo Code Talkers

Navajo Code Talkers' Dictionary

Related links

The best Indian movies

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.