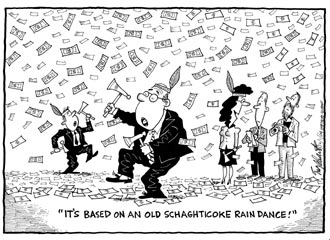

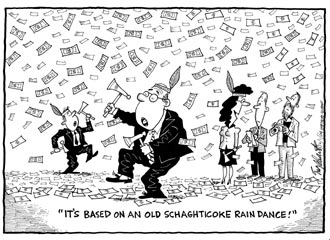

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

The Festering Problem of Indian "Sovereignty"

By Jan Golab

Foxwoods, the King Kong of casinos, was brought to Connecticut with dreams of untold riches. Now, locals are trying to kill the beast. Foxwoods and its sister institution, Mohegan Sun, (the world's two most profitable casinos), pay host state Connecticut a hefty $400 million a year—one fourth of the take. Yet in 2003, Connecticut became the first state in the country to pass legislation designed to halt any future casino development. The measure passed unanimously, not exactly a ringing endorsement for Indian gambling institutions. "Another gambling palace anywhere in the state would be disastrous," the Hartford Courant warned in an editorial. "The state must stop this slot-machine tsunami."

Jeff Benedict is president of the Connecticut Alliance Against Casino Expansion, and the author of Without Reservation, a book about the Mashantucket Pequot Indians and their Foxwoods casino. "Casino money costs us a lot more than it's worth," Benedict argues. He recites a litany of woes: Casinos have a negative impact on roads, water and land consumption, fire, police, ambulance service, air pollution, and traffic. Local school systems are flooded with the children of low-income casino workers, who also create a shortage of affordable housing. And there are social costs—increased bankruptcies, foreclosures, divorces, child abuse, and crime. "The closer a community gets to a casino, the higher those numbers are," says Benedict. "Who pays for that? The local and state governments."

Casinos cause property devaluation and lost taxes when businesses and lands are taken over by tax-exempt tribes. While casino owners argue that they create jobs and help neighboring businesses, the casinos (which, as Indian enterprises, do not have to pay the same taxes or abide by the same laws as other establishments) actually damage competing businesses nearby—restaurants, bars, hotels, retail outlets. "When the Indian casino comes to town, nobody else does well," says Benedict.

Except for the lawyers. The Pequots have subjected their host state and local governments to a decade of legal battles over tribal land annexation, environmental and land-use regulations, and sovereign immunity from lawsuits and police jurisdiction. Local communities have spent millions litigating against further casino expansion. Twelve more would-be "tribes" are petitioning the Bureau of Indian Affairs for federal tribal status, and new land claims threaten over one third of Connecticut's real estate.

Another book on Foxwoods, Hitting the Jackpot, by Wall Street reporter Brett Fromson, explains how a "tribe" that disappeared 300 years ago resurrected itself and won a gambling monopoly now worth $1.2 billion a year. Like Benedict, Fromson concludes that the re-created Pequot tribe is illegitimate, a political contrivance based on sympathy and political correctness, not reality or common sense—"the greatest legal scam."

Next door in New York, the situation is even worse. The Empire State approved the Oneida Nation's Turning Stone Casino near Oneida ten years ago, without first obtaining any agreement for the Nation to share its revenues ($232 million in 2001) with the state, or any agreement to settle the tribe's claim to 250,000 acres of central New York land. Subsequent casino compacts with other tribes have been haphazard and subject to ongoing renegotiation, with New York collecting money from some, not from others.

The Oneidas have used their casino cash machine to buy 16,000 acres of land and businesses, including nearly all of the area's gasoline and convenience stores. Once they are Indian-owned, the land and businesses go off the tax rolls. The business impact and loss of property and sales taxes has some local communities teetering on bankruptcy. "The tribes hurt us in a number of ways," explains Scott Peterman, president of Upstate Citizens for Equality. "They buy a property and refuse to pay property tax because they say they are re-acquiring their ancient reservation. Then they open a business on that property and refuse to collect sales tax."

By undercutting all non-Indian businesses that collect taxes, tribal sales of gasoline and cigarettes alone cost New York state millions of dollars in annual taxes. The Supreme Court ruled in 1994 that states could tax tribal sales to non-native customers, but so far, New York has failed to enforce this over Indian resistance. One tribe, the Onondaga, sells an estimated 20,000 cartons of cigarettes every week, or $26 million worth a year. Governor George Pataki tried to collect in 1997, but he backed down when Indian protestors blocked the New York State Thruway. Last year, the state legislature ordered Pataki to begin collecting the taxes, which it conservatively estimated would amount to $165 million in 2003 and $330 million in 2004. The Syracuse Post-Standard reported: "Indian Cig Sales cost NY $436M." Another study estimated that New York tribes cost the state a total of $895 million last year. Still, the tab remains open.

The state with the most tribal casinos—82—is Oklahoma, where tribes rake in as much as $1.2 billion a year—and the state doesn't get a cent. Oklahoma Indians, who comprise 7 percent of the state population, have become the most powerful political force there. Meanwhile, officials estimate that Oklahoma's 39 tribes cost the state $500 million a year—in lost property taxes, lost revenues on tax-free cigarettes, and lost excise taxes and tag fees from cars sold by reservation dealerships. That's nearly the equivalent of the state's 2003 budgetary shortfall, enough to pay for 17,000 teachers. Meanwhile, the state's billion-dollar racetrack industry, which does pay taxes, is teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, and communities are mired in litigation with cash-flush tribes over land and water rights.

As Connecticut, New York, and Oklahoma wrestle to control their Indian casinos, California's casinos are rapidly expanding, and many other states, like Pennsylvania and Maryland, are just gearing up. Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger's legacy will largely be a matter of whether or not he allows the Golden State to become the new Nevada. With their state monopoly on gambling, California Indians could eventually become the richest people on earth. Their 54 casinos are already raking in $5 billion a year, which isn't far behind the entire Las Vegas area ($7.7 billion), and they are pushing for more. With 107 federally recognized Indian reservations and rancherias—more than anywhere else in the country—California could easily surpass Nevada as the nation's gambling capital in the next few years.

Yet tribal chairmen blast the California governor for suggesting that they "pay their fair share." They insist that: "Governments cannot tax other governments!" They insist they are "sovereign."

"Sovereign" usually means "independent." American Indians, however, are completely dependent on their host governments—for roads, power, water, fire and police protection, schools, universities, hospitals, and health care facilities. "The technical term for Indian reservations is 'domestic dependent nations,'" explains one legislative analyst. "They are not foreign governments. They have no foreign policy powers. They are not allowed to sell their land to anyone outside the U.S. and they are not allowed to maintain relations with any foreign nation. To regard them as being like foreign nations inside our nation is very problematic. How can Congress create a government within a state, with powers that Congress itself could never possess?"

The notion that American Indian tribes should be treated like Canada or France, as some tribal leaders assert, offends common sense. "A nation within the nation" is what they claim to be, but it is not even close to a reality. If they are independent nations, why have Indians been allowed to donate over $150 million to U.S. political campaigns and become our nation's most influential political special interest group?

Californians have already shown their disgust for the "pay-to-play" politics that linked Indians to ousted governor Gray Davis and his lieutenant governor Cruz Bustamante, who did the Indians' bidding while taking $12 million of their cash. Experts say that is only the tip of the iceberg. Senator Barbara Boxer (D-California) and Representatives George Miller (D-Richmond), Mary Bono (R-Palm Springs), Hilda Solis (D-East L.A.), and Joe Baca (D-San Bernardino) have long served as legislative activists to expand tribal sovereignty. They have pushed through legislation to recognize "tribes" so they can avoid a lengthy and complicated federal recognition process that includes oversight by the governor and secretary of the interior. This form of "reservation shopping" via sympathetic legislation is responsible for many new gambling resorts.

Senator Boxer pushed a bill through Congress granting federal recognition to the Federated Coast Miwoks of Graton Rancheria, a small landless "tribe," after receiving assurances they would not open a casino. But then the tribe hired a team of advisers, including Boxer's son Doug, and announced plans for a massive $100 million Nevada-financed casino and resort in California's wine country. Four city council members in Rohnert Park, the proposed site of the resort, are now facing a grassroots recall for selling out to the Indians.

Another small tribe, the 70-member Ione Band of Miwok Indians, had no interest in pursuing a casino until the tribe was hijacked by officials from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. These agents, in a move not uncommon in the murky world of Indian politics, opened the tribe's membership rolls against the wishes of the tribal leadership and added 450 new members, including the BIA officials themselves and their families. These new "tribal members" then called for an election and overthrew the existing tribal leadership. The BIA officials not only made themselves members of a tribe they were administering, they took it over—for the purpose of promoting (and profiting from) a $100 million casino in Plymouth, California. Four members of Congress have called for an investigation into the Ione Miwok takeover.

Corruption like this seems the inevitable consequence so long as Indians are allowed to operate outside American law under a claim of tribal sovereignty. A coalition of 18 attorneys general from western states recently identified "corruption on tribal lands" as their number one concern, even over international terrorism. Many federally identified "high intensity drug trafficking areas" are located on tribal lands. Immigrant smuggling is also a serious problem on reservations that adjoin our international borders with Canada and Mexico. Authorities are also concerned that Indian casino cash makes a tempting target for international terrorists who need to launder money. With revenues of $14 billion last year, Indian gaming is a prime target for money cleaners of all sorts.

When gambling isn't properly regulated it attracts money laundering, loan sharking, drugs, and organized crime. Investigators with the federal Indian Gaming Commission are able to make only occasional visits to the more than 241 Indian gaming operations across the country. The Commission has only two investigators and one auditor for the entire West Coast. John Hensley, the chairman of the California Gambling Control Commission under Governor Davis, resigned in frustration due to a lack of funds (and his outrage over Davis's promise that if he was not recalled as governor he would allow the tribes to pick two new members for the Commission).

This lack of oversight is a recipe for disaster. "We certainly would not let private casinos in Nevada self-regulate," notes Whittier Law School professor and national gambling expert Nelson Rose. Since 1980, more than 130 state and local officials have been drawn into gambling corruption scandals, according to a paper prepared by the Library of Congress. A variety of scandals has already touched tribes throughout the country, and law enforcement insiders predict that worse is yet to come. Concerns are heightened due to the industry's newfound political influence. Some tribal leaders have already been indicted for engineering illegal campaign contributions.

Investors in a Rincon tribe operation in San Diego County were accused of plotting to launder more than $2 million for a Pittsburgh crime family. Seventeen people were indicted, including a member of the Rincon tribal council. Ten people associated with Chicago crime boss John DiFonzo and a San Diego mobster were convicted of racketeering and extortion in another attempt to take over a tribal gambling hall. Members of the New York Seneca Nation are facing a RICO indictment for smuggling untaxed cigarettes. The Bureau of Indian Affairs says illegal drugs have deeply infiltrated Indian communities. In southern Arizona, $1.8 million in marijuana was seized in a single incident on the Tohono O'odham reservation. An estimated 1,500 illegal Mexican immigrants a day also cross the border into that 2.8 million-acre reservation. The Akwesasne Reservation on the U.S.-Canadian border, according to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, is "a major smuggling hub for goods illegally transported in and out of Canada from the U.S., or vice-versa—including narcotics, firearms, alcohol, tobacco, and illegal aliens." The movement of aliens there and in Arizona is considered a threat to homeland security. New York's Mohawk tribe was charged in 1999 with smuggling drugs, guns, and illegal aliens—including associates of Osama bin Laden—for as much as $47,000 a head. These sorts of problems will recur with increasing frequency in the future unless their true root—the non-applicability of standing U.S. laws on Indian lands due to claims of Native American sovereignty—is challenged.

"The debate over Indian sovereignty may seem abstract," explains one analyst, "but it gets very concrete when a state suddenly loses authority over a major portion of its land. Reservation shopping basically gives wealthy gambling tribes the ability to shrink counties and states"—and to place important personal actions and economic transactions beyond the reach of American law. Throughout the nation, whenever U.S. citizens battle tribes over problems with land, water, zoning disputes, personal injuries, firings, broken contracts, or other issues, the claim of tribal sovereignty often intervenes. As tribal governments expand, local governments lose their political power to protect their citizens, some of whom find themselves ruined by tribal sovereignty claims—like the rancher who lost all his water to a new tribal golf course and resort.

The Citizens Equal Rights Alliance and United Property Owners, umbrella organizations encompassing hundreds of grassroots groups affected by Indian sovereignty claims, represent some 3.5 million citizens and business and property owners affected by America's 550-plus Indian reservations. There are also independent organizations in 22 states, like One Nation in Oklahoma, Upstate Citizens for Equality in New York, and Stand Up for California.

Activists in this rapidly growing anti-sovereignty movement feel betrayed by their elected leaders. Indian sovereignty, they say, is a profoundly flawed special body of federal law—some say an outright scam—that creates bogus tribes, legalizes race-based monopolies, creates a special class of super-citizens immune to the laws that govern others, and Balkanizes America. "Sovereign rights based on race for a few American citizens is not, and will never be, reconcilable with the equality and civil rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution to all citizens," says Scott Peterman, of Upstate Citizens for Equality. "The concepts of equal rights, equal opportunities, equality under the law, and equal responsibilities for all citizens should not be bargained away by our politicians."

Many say that sovereignty is a concept from another age that no longer works today. "It goes back a century to when native populations had been dispossessed," explains former California senator Pete Wilson, "to when the U.S. was largely an agricultural nation and we did not have the kind of economy we have today." Wilson says that when the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) was enacted in 1988, it didn't get nearly the attention it deserved. "A lot of people [in Congress] voted for it thinking that it amounted to little more than Bingo on reservations…. They didn't see it as a commercial enterprise that would transform reservations and their surrounding communities."

Most analysts concur that IGRA is a terrible law—vague, fuzzy, and unclear. "Congress should have spelled out much more clearly what the tribes are allowed to do," explains one analyst. "IGRA has subsequently been interpreted by the courts to mean that a state can pass a ballot initiative granting a lucrative monopoly on gambling, based solely on race, within a state that does not otherwise allow gambling. It defies the basic principles of equal protection, and gives cause to wonder. Should we give Hispanics the liquor industry? Should blacks get cigarettes? What about the Asian boat people?"

IGRA became a mechanism for the gambling industry to enter states where gambling had been illegal for more than a century, allowing it to operate outside the legal jurisdiction of the state governments. It pitted tribes against tribes, and tribal leaders against their own members, and created impossible entanglements of governance and jurisdiction. IGRA essentially created an attractive investment opportunity for the gaming industry, much as minority-contracting rules created an industry out of finding black and Hispanic figurehead partners with which to pursue government contracts. The potential gambling revenues made it attractive for marginal groups to seek tribal status, specifically for the purpose of opening a gaming franchise. "The groups in some cases are so marginal it's almost laughable, "says one legislative analyst. "Often they are subdivisions of actual tribes—the left-fork wing of the old river Indian tribe. It's not about tribal identity. What they really want is a casino."

Experts contend that Congress never intended sovereign status for every parcel of land granted to Indians. The small California rancherias, for example, were meant to host housing projects for landless Indians. One such group of federal housing recipients-turned-Indian-tribe, the Auburns, have used their new sovereign status to open the massive Thunder Valley casino near Sacramento. The Auburns are descendants of 40 Indians who were set up on a few dozen acres of public housing in 1910. "Do you really think Congress intended for them to be a sovereign nation over which state law would have no force?" asks one legislative analyst who specializes in Indian law.

Scott Peterman says the Indian sovereignty problem will ultimately have to be solved by Congress, a sentiment echoed by many other observers across the nation. "They are the ones who created the mess," says Peterman. He believes Congress should terminate tribal sovereignty definitively. "The irony is, the tribes claim they need sovereignty to preserve their culture, but they use it to build casinos. They talk about 'mother earth,' but they are more than willing to trade land for slot machines. Many tribal governments are so corrupt they are a bigger enemy to Indian culture than anybody. The Amish, Quakers, and Mennonites preserve their culture better than any Indian tribe, and they do it while paying taxes. Indians don't need sovereignty, or a whole federal bureau, to maintain their culture."

For many years, the Supreme Court avoided the big questions and made up Indian law by carving off issues piecemeal. In 1998, the Court concluded that the doctrine of tribal sovereign immunity was outdated, but it also concluded that Congress, not the courts, needed to fix it.

President Bush has at least moved to halt the march toward expanded sovereignty. Several tribes pushed President Clinton to enact more-liberal rules that would have made it even easier for tribes to reservation shop. President Bush withdrew those relaxed rules. Tom Grey, director of the National Coalition Against Gambling Expansion, advised President Bush in a 2003 letter that "if pending approval of more than 200 self-described 'Indian Tribes' is not denied, there will be a veritable explosion of gambling emporiums throughout America, threatening local economies, increasing addiction and concomitant criminality, and disrupting social and political stability."

When it comes to sovereignty, everyone seems to agree that Congress will eventually have to "mend it or end it." Congress has the power to shape and re-shape the relevant laws as it sees fit. The problem is a lack of will, due largely to ignorance or fear of the fast-growing political clout of tiny gambling-enriched tribes who have shown a great willingness to use their lucre for political donations.

Currently, nearly all Indian legislation is controlled by pro-tribal forces, particularly in the Senate. Hawaiian Daniel Inouye, the ranking minority member of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee, and Ben Nighthorse Campbell of Colorado, chairman of that committee, along with Daniel Akaka from Hawaii and Arizona's John McCain, have virtual veto power over any Indian-related bill. "I believe we are headed for a reconsideration of tribal sovereignty," states one public official who asked not to be identified, "but it won't happen until Senators Inouye and Campbell are no longer in office."

And while many in Congress are having second thoughts about tribal sovereignty, others continue to work to expand it, sometimes with the enticement of ample campaign donations. Senator Elizabeth Dole has a bill calling for recognition of the Lumbee Nation of North Carolina, and fellow Republican, Senator George Allen, is backing a measure to recognize six new tribes in Virginia. The Native Hawaiian Bill would grant tribal status to some 400,000 Hawaiians, creating the biggest tribe in the country and virtual apartheid in the fiftieth state. "Tribal sovereignty is going to be a hard thing to beat because the politicians are ignorant," says Scott Peterman. "They think sovereignty is good for the Indians, but it isn't. It's good for the tribal governments, not for individual Indians."

In 1993, Bill Clinton's head of the BIA, Aida Deer, decreed that every one of Alaska's 231 native villages was a tribe, thereby doubling the state's tribes with the stroke of a pen. Sovereignty advocates now want each village to be fully recognized as a sovereign nation. "That course of action cannot succeed," Alaska Senator Ted Stevens told the Alaska Federation of Natives at its annual convention in 2003. "If those villages are recognized as sovereign nations, the future of Alaska as a state is in jeopardy: Alaska would ultimately encompass a huge collection of independent tribal nations, unconnected by a state government and unprotected by the federal system."

Stevens, who championed Alaskan statehood back in the 1950s and became a senator in 1968, added a rejoinder to opponents who called him a bigot for defending that line of argument. "There are reasonable differences of opinion. But to be called a racist after more than 50 years of dedicated service to Alaskans, particularly Alaskan natives, is something I will not forget. It is a stain on my soul."

Despite Arnold Schwarzenegger's success in standing up to the Indian tribes of California, most elected officials are afraid to address the issue of sovereignty. Like Social Security and illegal immigration, some view it as a "third rail" issue—touch it and you die. Some Indians insist that sovereignty is the essence of being an American Indian, so they respond to any questioning of sovereignty as a personal attack on Indians. Those who question sovereignty are frequently denounced as racist. Former Washington senator Slade Gorton was actually a defender of tribal sovereignty except when it trampled on non-Indian rights, and for even that mild reservation, he was branded "The Indian Fighter" and demagogued as racist, which contributed to his narrow defeat in 2000 by Maria Cantwell.

Because of the volatility of the sovereignty issue, more than a dozen senators and congressmen declined to be interviewed for this story. Many of their aides who did talk asked not to be identified. "Politicians are afraid to speak out and have their views seen in print," explains one activist, "because then tribes will spend big money to get them un-elected." Indeed, Indian tribes now spend more on elections than any other interest group in America.

"Tribal gaming has created a terrific inequality between tribes, and the people who have benefited are only a tiny percentage of American Indians," says one government official who asked not to be identified. "If you're a bogus six-member tribe with a fabulous location for a casino, all six of you get tremendously wealthy. But if you're a genuine, historic tribe in a remote location, like the Standing Rock Sioux of North Dakota, you accrue little or no benefit." Indeed, almost half of the nation's Indian population lives in five states—Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Oklahoma—that account for only a small percentage of Indian gaming revenues.

The same official is skeptical that any politician will have the guts to stand up to the Indians until everyday Americans are up in arms. He even bets that Governor Schwarzenegger will go belly-up on the issue. "I've seen too many elected officials challenge the tribes, then gradually work their way back to an accommodation. At the end of the day, he'll be a blood brother."

Not everyone is so cynical, or afraid. Representatives Frank Wolf (R-VA) and Christopher Shays (R-CT) have long championed legislation to halt the headlong expansion of Indian gambling. Last February, they introduced a bill that would require all new gambling casinos to be approved by state legislatures. Wolf admits that the bill's chances right now are not good. "That's because many of our leaders still don't know there is a problem," he says. "That probably won't change until there is a great public outcry from communities around the country.... The media also needs to pick this up. The Indians are being exploited by gambling interests."

Another outspoken Congressman on the issue is Republican Ernest Istook of Oklahoma. "We have certainly reached a point where something needs to be done," he says. "But that's not the same as the point where people recognize that need, or are prepared to act on it." Istook has noticed a concerted effort by Indian interests to convince the public that the issue is beyond the reach of the democratic process. "There is often a misconception that nothing can be done. That's inaccurate. It is very clear that Congress has broad and unfettered authority to deal with these issues, and could do so if it were willing. Tribal sovereignty is subject to the jurisdiction of the Congress—which could change it, or even undo it altogether."

"The challenge is that sovereignty means different things to different people. What we need to do is follow the Constitutional standards of equal protection, for tribes and non-tribes. You will not solve the problems of Indian tribes by giving them a legal status different from everybody else. Secondly, we need to allow tribes to have control of their own assets so they have less temptation to resort to special treatment. Feelings of mistreatment often lead them to take unfair advantage with regard to sovereignty. And we need to create more economic opportunities that are not dependent on special status and treatment."

We are headed for more conflict, even disaster, says Istook, if we don't soon address this basic violation of fundamental American principles: In our recent dealings with Indians, Istook says, "we've created a system where some people have more rights than others, and that directly conflicts with American traditions and history. It not only attacks the principle of equal rights, it attacks the root of democratic governance. We need to use something stronger than guilt to resolve these issues."

Many experts believe it will take years before the inevitable day of reckoning on sovereignty finally reaches the halls of Congress. But the public mood is changing rapidly in certain places. Some observers believe this subject could mature into a bona fide political issue much sooner.

As executive director of United Property Owners and a national spokesperson for One Nation, Barb Lindsay represents more than 300,000 property owners, scores of grassroots community groups, dozens of local governments, and thousands of small businesses. Part Indian herself, Lindsay has been lobbying in Washington for ten years. She has emerged as one of the leading voices in the growing national movement challenging tribal sovereignty.

"Five years ago, people didn't know anything about tribal sovereignty," Lindsay explains. "Indian gaming has really elevated the issue in terms of public awareness, and with elected officials and their staffs. A few years ago they were not very sympathetic to our cause, because all they knew was tribal positions. But with growing problems in states like Connecticut, California, Wisconsin, New York, Oregon, Washington, and Oklahoma, more Congressmen are having problems in their own districts. They see tribes running roughshod over local citizens, ignoring environment laws and land-use codes and water rights. Instead of the Dances with Wolves Hollywood mythology they've been sold, they are now facing the reality of dealing with a group of people who believe they are somehow above the law."

The true meaning of sovereignty, Lindsay says, is tax evasion. "It is no coincidence that the states now facing the biggest budget deficits are also the states with the largest number of tax-exempt Indian casinos and tax-evading tribal businesses. It is widely recognized that IGRA is being abused and Indian casino reservation shopping is undermining local, county, and state tax bases and changing community character and quality of life, while simultaneously denying local citizens a voice in how the future of their community will be shaped."

Others concur that America's tribes need to practice sovereignty in a way that is responsibly congruent with the laws of their "host nations" (state and local governments). If Indians choose the endless warpath, some observers say, they will eventually lose the war, and "sovereignty." This is difficult for some tribes to accept, because they have achieved their current success and financial bonanzas through two decades of aggressive court battles and relentless warfare with the states. But that war is over and they have won. They now need a new, cooperative strategy, or they may awaken resistance in their neighbors.

Many groups have been mistreated in history—blacks, Jews, Asians, Poles, the Irish. "Should each of these groups be given a sovereign land within the United States and allowed to govern as they choose, free from taxes that must be paid by others, and free to engage in activities denied to others?" asks Henry Lamb, chairman of Sovereignty International. "Americans are defined not by color, religion, or ethnicity, but by a belief in, and dedication to, the principles of freedom, as defined in our founding documents. As a nation, we seem to have forgotten this fundamental principle."

Published in One America September 2004

Rob's reply

Not since Time magazine's lengthy 2002 "expose" has someone written such a false, misleading "analysis" of Indian gaming. Let's see how many ways Jan Golab got it wrong:

>> He recites a litany of woes: Casinos have a negative impact on roads, water and land consumption, fire, police, ambulance service, air pollution, and traffic. <<

Most of these so-called woes are undocumented. Some are patently ridiculous. Almost all Indian casinos are on existing reservations, for instance, so they don't consume any non-reservation land.

How would a casino increase the need for fire or ambulance services? If a patron lights a fire or drops dead in a casino, for instance, that means he doesn't light a fire or drop dead at home. The net effect on the community is zero.

Air pollution is only worse if you assume people would've stayed home if the casino weren't available as an entertainment option. Another possibility is that the people would've driven to other entertainment locations—perhaps sites further away. You can't know what they would've done unless you conduct an experiment far more elaborate than anyone could do.

In short, most studies show Indian casinos are a mixed blessing, with the drawbacks not outweighing the benefits. That's why most communities that have casinos approve of them after they get used to them.

>> Local school systems are flooded with the children of low-income casino workers, who also create a shortage of affordable housing. <<

Another ridiculous charge. If the casino workers are local, their children already go to local schools. If they're not local, their children just transfer from other schools. Casinos do not create additional children unless their patrons get extremely lucky.

The attitude expressed above is merely a NIMBY attitude toward any new business. It would apply equally to any new business of equal size. It's not specific to casinos or Indian casinos.

>> Casinos cause property devaluation and lost taxes when businesses and lands are taken over by tax-exempt tribes. <<

"When"? How about "if"? Again, most gaming tribes operate their casinos on existing reservation land. They don't take over other land. Similarly, most Indian casinos don't "take over" other businesses, and certainly not businesses outside the reservations. Casinos are in the casino business, not the "other" business.

Furthermore, if a tribe takes over a non-tribal business on non-tribal land, it still must pay state and local taxes. The only case where the above statement applies is when the tribe takes over a non-tribal business on tribal land. That's rare and doesn't justify Golab's false and misleading statement.

>> While casino owners argue that they create jobs and help neighboring businesses, the casinos (which, as Indian enterprises, do not have to pay the same taxes or abide by the same laws as other establishments) actually damage competing businesses nearby—restaurants, bars, hotels, retail outlets. <<

Another statement that studies don't necessarily bear out. And how would a casino damage a "retail outlet"? A supermarket, hardware store, or clothing store is not a "competing business" with a casino. Their customers shouldn't overlap.

>> The Pequots have subjected their host state and local governments to a decade of legal battles over tribal land annexation, environmental and land-use regulations, and sovereign immunity from lawsuits and police jurisdiction. <<

This is obviously a loaded statement. Tribes generally don't sue a state over the state's environmental or land-use regulations. The state sues the tribe. So it's more correct to say Connecticut has subjected its Indian governments to a decade of legal battles.

>> Twelve more would-be "tribes" are petitioning the Bureau of Indian Affairs for federal tribal status <<

Another scare tactic. If these petitions are like most petitions, the BIA will turn them down.

>> new land claims threaten over one third of Connecticut's real estate. <<

Another scare tactic. The Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes are claiming a fourth of Colorado, but no one thinks they're going to win their claim.

>> Another book on Foxwoods, Hitting the Jackpot, by Wall Street reporter Brett Fromson, explains how a "tribe" that disappeared 300 years ago resurrected itself and won a gambling monopoly now worth $1.2 billion a year. <<

See Pequots Are About as Indian "as Camilla Parker Bowles" for the latest debunking of Fromson's hyperbolic claims. Read about him and his fellow critics at The Critics of Indian Gaming—and Why They're Wrong.

>> Next door in New York, the situation is even worse. The Empire State approved the Oneida Nation's Turning Stone Casino near Oneida ten years ago, without first obtaining any agreement for the Nation to share its revenues ($232 million in 2001) with the state, or any agreement to settle the tribe's claim to 250,000 acres of central New York land. <<

Assuming the above is true, the proper response is...so? One, it's a unique situation. It doesn't apply to other gaming tribes. Two, tribes aren't obligated to settle all outstanding claims to get a gaming compact. Three, this happened ten years ago, when people didn't know Indian casinos would be so successful. The states have more information these days and can negotiate better compacts.

In short, this is yet another scare tactic.

>> Subsequent casino compacts with other tribes have been haphazard and subject to ongoing renegotiation, with New York collecting money from some, not from others. <<

Most compacts have an expiration date, so of course they're subject to renegotiation. As for their "haphazard" nature, whose fault is that? The state of New York's, presumably.

If New York can't negotiate compacts properly, how does that impugn the Indian gaming industry? It's like saying that because Southern California had a protracted grocery-store strike, with neither side making concessions, we should shut down grocery stores everywhere. It's ridiculous.

>> The business impact and loss of property and sales taxes has some local communities teetering on bankruptcy. "The tribes hurt us in a number of ways," explains Scott Peterman, president of Upstate Citizens for Equality. <<

Here's where Golab's biases start becoming clear. Upstate Citizens for Equality (UCE) is a rabidly anti-Indian, anti-gaming organization. Its founders chose the deceptively "fair-sounding" name precisely to deceive people about its true intent. For Golab to quote its president without giving any of UCE's history, without even mentioning what the organization stands for, is a failure of journalistic ethics.

>> By undercutting all non-Indian businesses that collect taxes, tribal sales of gasoline and cigarettes alone cost New York state millions of dollars in annual taxes. <<

This is the same phony argument business use when they talk about the loss of software or CD sales due to piracy. Fact is, people wouldn't have bought as much gasoline or cigarettes if they weren't so cheap. That means the alleged losses are grossly magnified. They're a guess at what consumers would've bought if the tribal businesses didn't exist.

>> The state with the most tribal casinos—82—is Oklahoma, where tribes rake in as much as $1.2 billion a year—and the state doesn't get a cent. <<

Again, that's an example of poor negotiating skills, not a problem inherent in Indian gaming. Oklahoma's tribes are negotiating new compacts now and they'll pay a substantial amount to the state. So what's the problem?

>> Oklahoma Indians, who comprise 7 percent of the state population, have become the most powerful political force there. <<

I've never heard anyone claim that. In California, yes, but not in Oklahoma. What's the source or justification for this statement?

>> Meanwhile, officials estimate that Oklahoma's 39 tribes cost the state $500 million a year—in lost property taxes, lost revenues on tax-free cigarettes, and lost excise taxes and tag fees from cars sold by reservation dealerships. <<

More assumptions about what consumers would've bought if the cheaper alternatives hadn't been available. And I hope the "lost property taxes" figure doesn't include land that's always been under Indian control. That land wasn't lost recently and states have never had the right to tax it. Claiming it as a lost revenue source would be false and ignorant.

>> Meanwhile, the state's billion-dollar racetrack industry, which does pay taxes, is teetering on the edge of bankruptcy <<

Not a problem attributable to Indian gaming. The racetrack industry is doing poorly in many places, whether the locales have Indian casinos nearby or not.

>> Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger's legacy will largely be a matter of whether or not he allows the Golden State to become the new Nevada. <<

An unsubstantiated opinion. Actually, it appears Schwarzenegger's legacy will largely be a matter of whether he can solve California's perennial budget crisis. So far the answer appears to be no.

>> With their state monopoly on gambling, California Indians could eventually become the richest people on earth. <<

Richer than Arab oil sheiks? What's the basis for this outrageous claim? Another unsubstantiated opinion, another scare tactic.

>> "Sovereign" usually means "independent." <<

Not quite. Independence is one aspect of sovereignty, but the words aren't identical. The King of England has always been sovereign, for instance, even though Parliament increasingly subjected him to its decisions.

>> American Indians, however, are completely dependent on their host governments—for roads, power, water, fire and police protection, schools, universities, hospitals, and health care facilities. <<

Wrong again. They're partly dependent on their "host governments" for these things. Many tribes operate their own police and fire departments, schools, and health care facilities.

Congress created tribes?

>> "...How can Congress create a government within a state, with powers that Congress itself could never possess?" <<

Here's the crux of Golab's problem. Congress didn't create tribal governments. Tribal governments existed before the US government did. When the Founding Fathers wrote the US Constitution, they recognized this fact. When US Supreme Court ruled on the US Constitution, it recognized this fact.

Note that Golab starts quoting unnamed legislative analysts here. Journalists recently have denounced the use of unnamed sources in controversial stories. Why? Because innocuous-sounding sources such as "analysts" often have an axe to grind. They work for politicians who reap political power if their views become the prevailing ones.

That gives these unnamed analysts a powerful incentive to bend the truth to their bosses' aims. If they support their bosses, they'll get rewarded with promotions and other perks. So unless you know a source's name, you should assume the person share's Golab's bias against Indians and gaming.

>> If they are independent nations, why have Indians been allowed to donate over $150 million to U.S. political campaigns and become our nation's most influential political special interest group? <<

No one said Indian nations are "independent," so this is a straw-man argument. By law, they have a unique status as semi-sovereign and semi-independent nations. Befitting their unique status, they can do some things that state and local governments can't do, but not others.

Who knows where Golab got the $150 million figure? Not me. I do know that during his campaign for governor, Schwarzenegger claimed California's tribes had spent $120 million to influence politicians. That claim was false.

That Indians are "our nation's most influential political special interest group" is another unsubstantiated opinion and scare tactic. And note how Golab has switched subjects from the rich gaming tribes, which may influence politicians, to all Indians—whether they conduct gaming or not, whether they're rich or not. This is stereotypical race-baiting. It suggests that all Indians are doing what a few are doing.

>> They have pushed through legislation to recognize "tribes" so they can avoid a lengthy and complicated federal recognition process that includes oversight by the governor and secretary of the interior. <<

Despite Golab's calm language, it's clear she (?) doesn't understand the recognition process and is trying to scare readers. Governors don't have anything to do with the recognition process and the Secretary of the Interior doesn't have much to do with it. The Bureau of Indian Affairs is the primary arbiter of federal recognition.

More important, I believe this sentence contains a mishmash of claims. Golab has confused legislation to grant recognition with legislation to settle land claims, which isn't the same thing. She's confused legislation that passed and legislation that died. I'm pretty sure we're not talking about five successful cases of granting tribes recognition through Congress rather than the BIA.

Even if there were five legitimate cases of bypassing the recognition process, it begs a number of questions. Did these tribes seek recognition before or after the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988? Do these tribes have any gaming prospects or plans? Are they anywhere near urban locations?

How will five tribes out of 560-plus tribes affect the gaming equation, anyway? Probably not significantly, that's how.

For the facts on the number of recently recognized tribes, see NY Times: Most Would-Be Tribes Have Emerged Since 1988.

>> This form of "reservation shopping" via sympathetic legislation is responsible for many new gambling resorts. <<

More evidence that Golab is intentionally or unintentionally misstating the recognition process. "Reservation shopping" is the practice of casino companies searching for tribes to build new casinos, preferably by taking land into trust near urban locations. It can be done with existing tribes and doesn't necessarily have anything to do with recognizing new tribes.

Another gross misstatement of the facts, again showing Golab's bias. Here's the actual story:

The Coastal Post -- April 2000

We Are Still Here!The earliest historical account of the Coast Miwok people-whose traditional homeland stretched as far north as Bodega Bay and as far east as the town of Sonoma and included all of present-day Marin County-dates back to 1579. The group's federal status as a recognized tribe was terminated in 1966 under the California Rancheria Act of 1958.

The upsurge began more than five years ago, when the Coast Miwoks filed a petition with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to begin the lengthy federal acknowledgment process and thus gain certain benefits. The group was spurred into action when Cloverdale Pomo leader Jeff Wilson unsuccessfully attempted several times to establish gaming facilities, including a multi-million destination resort and casino just south of Petaluma on what the Coast Miwoks claimed was their territory.

In the interim, the Miwok tribe discovered a small parcel of land in Graton that had been set aside as a reservation area for the local Miwoks in the 1920s. This discovery of their own land, albeit now only about an acre, allowed the group to switch from a federal recognition process to a restoration process, which requires an act of Congress.

The Tribe, which rents an office in Petaluma, changed its name to the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, so that it could include various families from different locales. It has about 370 members.

Golab prefaced this remark by stating how Californians were disgusted with pro-Indian politicians like Boxer. As of 2005, Boxer has been elected three times to the Senate by large margins. She's arguably one of the state's most popular politicians. So much for the voters' disgust.

>> Another small tribe, the 70-member Ione Band of Miwok Indians, had no interest in pursuing a casino until the tribe was hijacked by officials from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. <<

I believe the Dept. of Justice investigated and the FBI is investigating this situation. Neither has found any crime yet.

>> Corruption like this seems the inevitable consequence so long as Indians are allowed to operate outside American law under a claim of tribal sovereignty. <<

"Corruption"? What corruption? The tiny Ione Band's corruption?

Golab hasn't documented any corruption, except perhaps this last case. What she's "documented" is 1) states that negotiated compacts poorly because they didn't know any better; 2) tribal businesses exercising their tax-free status legally; 3) tribal governments donating money to politicians legally; 4) Congress recognizing tribes through legislation rather than the BIA legally.

>> A coalition of 18 attorneys general from western states recently identified "corruption on tribal lands" as their number one concern, even over international terrorism. <<

I Googled this alleged quote. The only instances of it in Google's millions of pages were in copies of Golab's essay. That suggests the quote doesn't exist.

And if it did exist, it would refer to general problems on tribal lands, not problems specific to Indian gaming. In other words, it would be irrelevant to the subject of Indian gaming.

It also would be irrelevant to the subject of tribal sovereignty, unless Golab proves a link. As everyone knows, federal, state, and local governments have been corrupt throughout US history, even though they were sovereign entities. Therefore, Golab cannot claim that sovereignty somehow causes corruption.

>> Many federally identified "high intensity drug trafficking areas" are located on tribal lands. Immigrant smuggling is also a serious problem on reservations that adjoin our international borders with Canada and Mexico. <<

Not an Indian gaming issue. Not a tribal sovereignty issue.

>> Authorities are also concerned that Indian casino cash makes a tempting target for international terrorists who need to launder money. With revenues of $14 billion last year, Indian gaming is a prime target for money cleaners of all sorts. <<

A concern isn't even a problem, much less an actual crime. When this concern transforms into a problem or an actual crime, then Golab can alert us. Until then, it's a scare tactic.

The same applies to the claim that Indian gaming is a prime target for money launderers ("cleaners"). The US banking system in general is a prime target for money launderers. Does that mean we should shut it down?

>> When gambling isn't properly regulated it attracts money laundering, loan sharking, drugs, and organized crime. <<

This is a general gaming issue, not a specific Indian gaming issue. In fact, Indian gaming is properly regulated, so Golab's claim doesn't apply.

>> Investigators with the federal Indian Gaming Commission are able to make only occasional visits to the more than 241 Indian gaming operations across the country. The Commission has only two investigators and one auditor for the entire West Coast. <<

The National Indian Gaming Commission is the third of three levels of regulation over Indian gaming. Its role is mostly coordination and supervision, not direct oversight. To imply that the NIGC is the primary regulatory body is totally false. The NIGC doesn't have or seek the resources to do full, hands-on regulation because that isn't its job.

>> John Hensley, the chairman of the California Gambling Control Commission under Governor Davis, resigned in frustration due to a lack of funds (and his outrage over Davis's promise that if he was not recalled as governor he would allow the tribes to pick two new members for the Commission). <<

State gaming commissions are the second of three levels of regulation over Indian gaming. These commissions are more directly involved in regulatory oversight.

If Gov. Gray Davis or the California legislature didn't fund the California Gambling Control Commission sufficiently, that isn't an Indian gaming problem. It's a California government problem. The same applies to the governor's choice of commission members.

>> This lack of oversight is a recipe for disaster. <<

That might be true, if tribes didn't have the first of three levels of regulation: their own tribal regulatory agencies. These independent bodies have the primary responsibility for maintaining the integrity of Indian gaming. Judging by the overwhelming lack of crime and corruption in Indian casinos, these agencies must be doing their jobs. Disaster averted.

>> "We certainly would not let private casinos in Nevada self-regulate," notes Whittier Law School professor and national gambling expert Nelson Rose. <<

Wrong. Every company relies primarily on its own internal accounting and auditing procedures to keep its business honest. That's self-regulation. Like tribal casinos, many companies are also regulated or audited by outside agencies. That's how business works in the US. There's nothing unusual about it.

>> Since 1980, more than 130 state and local officials have been drawn into gambling corruption scandals, according to a paper prepared by the Library of Congress. <<

Again, a general gaming issue, not a specific Indian gaming issue.

Shocker: Governments sometimes scandalous

>> A variety of scandals has already touched tribes throughout the country, and law enforcement insiders predict that worse is yet to come. <<

What scandals? A "variety" isn't necessarily a large number. This is a general tribal issue, not a specific Indian gaming issue.

>> Some tribal leaders have already been indicted for engineering illegal campaign contributions. <<

Some? How many...five or ten? Out of how many...10,000? (Five hundred tribes x 20 leaders per tribe = 10,000.)

Again, this is a general tribal issue, not a specific Indian gaming issue. Tribes support candidates for many reasons, not just for their support of gaming.

>> Investors in a Rincon tribe operation in San Diego County were accused of plotting to launder more than $2 million for a Pittsburgh crime family. <<

This is the investors' fault and their problem. It's not an Indian gaming problem unless the investors succeeded, which they apparently didn't. And the charge is a decade old; it happened before the present growth of Indian gaming and Indian gaming regulation.

>> Ten people associated with Chicago crime boss John DiFonzo and a San Diego mobster were convicted of racketeering and extortion in another attempt to take over a tribal gambling hall. <<

Again, outsiders caused the problem and were to blame. The problem wasn't with the tribal casino or the tribe's leaders. And the fact that the mobsters were caught and convicted proves the regulatory system works.

So again, what's the problem? Should we shut down every business that tempts crime and corruption even if the criminals don't succeed? That would mean the end of business as we know it in the US.

>> Members of the New York Seneca Nation are facing a RICO indictment for smuggling untaxed cigarettes. <<

The members might claim they were legitimately exercising their sovereign rights. Anyway, an indictment isn't a conviction. And this is a tribal issue, not an Indian gaming issue.

>> The Bureau of Indian Affairs says illegal drugs have deeply infiltrated Indian communities. <<

Again, not an Indian gaming issue. Not a tribal sovereignty issue.

>> In southern Arizona, $1.8 million in marijuana was seized in a single incident on the Tohono O'odham reservation. <<

Not an Indian gaming issue. Not a tribal sovereignty issue.

>> An estimated 1,500 illegal Mexican immigrants a day also cross the border into that 2.8 million-acre reservation. <<

Not an Indian gaming issue. Not a tribal sovereignty issue.

>> The Akwesasne Reservation on the U.S.-Canadian border, according to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, is "a major smuggling hub for goods illegally transported in and out of Canada from the U.S., or vice-versa—including narcotics, firearms, alcohol, tobacco, and illegal aliens." <<

Not an Indian gaming issue. Not a tribal sovereignty issue.

>> New York's Mohawk tribe was charged in 1999 with smuggling drugs, guns, and illegal aliens—including associates of Osama bin Laden—for as much as $47,000 a head. <<

Not an Indian gaming issue. Not a tribal sovereignty issue.

>> These sorts of problems will recur with increasing frequency in the future unless their true root—the non-applicability of standing U.S. laws on Indian lands due to claims of Native American sovereignty—is challenged. <<

Whoops. Another blatant falsehood from Golab. Because tribes are only semi-sovereign, federal laws do apply on reservations. Only state and local laws don't apply. Illegal immigration, drug-running, and smuggling and are all federal crimes. The feds can and do pursue them on tribal lands.

Golab tacitly admits this when she writes that tribal members were charged with racketeering or smuggling, and marijuana was seized. How would these things be possible if tribes were literally sovereign and the feds couldn't operate on them?

Clearly, the feds are operating on reservations and successfully stopping crimes. That proves tribal sovereignty isn't the problem.

>> "The debate over Indian sovereignty may seem abstract," explains one analyst, "but it gets very concrete when a state suddenly loses authority over a major portion of its land. <<

Whoops. An obvious bait-and-switch tactic. States don't have any authority over immigration, drug-running, or smuggling crimes. These are federal concerns and the feds haven't lost their authority. Golab wants you to think feds have no power to stop crimes on reservations, but that just isn't so. She and her unnamed analyst are blatantly lying here.

>> Reservation shopping basically gives wealthy gambling tribes the ability to shrink counties and states"—and to place important personal actions and economic transactions beyond the reach of American law. <<

Beyond the reach of state law, maybe. Not beyond the reach of federal law. Federal environmental and criminal laws both apply to reservations. So when Golab refers to "American law," she's lying again.

At least she reverted to talking about wealthy gaming tribes. So why all the talk about crime on non-wealthy, non-gaming reservations? She's mixing apples and oranges in a blatant attempt to scare people.

>> Throughout the nation, whenever U.S. citizens battle tribes over problems with land, water, zoning disputes, personal injuries, firings, broken contracts, or other issues, the claim of tribal sovereignty often intervenes. <<

If so, then maybe "US citizens" should stop battling tribes over the tribes' rights and start acknowledging those rights.

Of course, Indians are US citizens also. They have been since 1924. This statement subtly portrays them as outsiders who don't fit into or comply with the system.

In reality, one set of US citizens is battling another set of US citizens over their mutual rights. That's the American way. It's up to the courts to decide whose rights are paramount in any given situation.

>> As tribal governments expand, local governments lose their political power to protect their citizens, some of whom find themselves ruined by tribal sovereignty claims—like the rancher who lost all his water to a new tribal golf course and resort. <<

"As tribal governments expand"...how? Opening a casino doesn't necessarily increase the size of a tribal government.

The rancher's claim is another undocumented one. And so what? Ranchers and farmers have been fighting over water with developers and cities ever since the West was colonized. This isn't a sovereignty or tribal issue, it's a general environmental issue. Developers taking water from farmers and ranchers must've happened a million times in US history.

>> The Citizens Equal Rights Alliance and United Property Owners, umbrella organizations encompassing hundreds of grassroots groups affected by Indian sovereignty claims, represent some 3.5 million citizens and business and property owners affected by America's 550-plus Indian reservations. <<

Like UCE, these are rabidly right-wing organizations that oppose tribal sovereignty, Indian gaming, and Indians in general. That Golab doesn't identify them as such shows her continuing bias.

>> There are also independent organizations in 22 states, like One Nation in Oklahoma, Upstate Citizens for Equality in New York, and Stand Up for California. <<

Golab already mentioned UCE. One Nation and Stand Up for California are also core members of the rabid, anti-Indian right.

>> Activists in this rapidly growing anti-sovereignty movement feel betrayed by their elected leaders. <<

Who cares how they feel? Elected leaders represent the silent majority, not the whining minority.

>> Indian sovereignty, they say, is a profoundly flawed special body of federal law—some say an outright scam—that creates bogus tribes, legalizes race-based monopolies, creates a special class of super-citizens immune to the laws that govern others, and Balkanizes America. <<

Here's a lineup of anti-Indian sentiments, thus proving what I said about these activists being anti-Indian. If these activists had their way, they would terminate the constitutional recognition of Indian nations...terminate legally-binding Indian treaties...terminate the tribes and their reservations...terminate Indians, period. People could be Indians only if they completely assimilated into the American mainstream. That is, if they were racially, socially, economically, politically, and legally identical to other Americans. If they stopped being Indians, in other words.

For more on the balkanizing issue, see Outside the So-Called Ethnic Box.

>> "Sovereign rights based on race for a few American citizens is not, and will never be, reconcilable with the equality and civil rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution to all citizens," says Scott Peterman, of Upstate Citizens for Equality. <<

Another quote from the known anti-Indian activist. Well, the quote is wrong. Sovereign Indian rights aren't based on race. They're based on the existence of Indian governments since the country was founded, regardless of the racial makeup of those governments.

US courts, whether liberal or conservative, have ruled on this issue so many times it isn't funny. They must rule on race-based lawsuits against Indians several times each year. As far as I know, no court has ever ruled that Indian rights are based on race rather than membership in a political body (a tribe).

See Indian Rights = Special Rights for more on the fallacy of Peterman's claims.

Sovereignty no longer works?

>> Many say that sovereignty is a concept from another age that no longer works today. <<

No longer works for whom...Indians? Note that Golab hasn't quoted a single Indian in this article. Now she's citing unnamed white people who think they know what's best for Indians. She probably won't find a single Indian, except maybe David Yeagley, who says sovereignty doesn't work and isn't beneficial.

In fact, recent studies have proved sovereignty is the best things Indian tribes have going for them. See Arguments Against Tribal Sovereignty for details.

Golab's whole premise is stupid and illogical if you think about it. California's gaming tribes are poised to become the richest people in the world...but sovereignty isn't working for them? In what sense is sovereignty hurting them...spiritually? If they're getting rich and gaining political influence—i.e., fulfilling the American Dream—one would have to conclude sovereignty is working just fine for them.

I'm guessing about 99% of Indians would agree sovereignty is working for tribes. But Golab implies these Indians don't know what they're talking about. All those scandals...that corruption...that crime. The only thing Golab left out is the poverty on reservations that don't have gaming. Why not blame that on gaming too, as Time magazine did?

If Indians universally support sovereignty even though it "no longer works," as Golab suggests, what does that tell us? Indians must be universally dumb and ignorant. They must be naive children squabbling in a playpen rather than mature leaders able to run modern governments. In short, they must be piggish and thuggish, savage and uncivilized. Why else would they be wallowing in the alleged scandal, corruption, and crime when they could simply give up gaming, forgo their sovereignty, and leave their reservations. When they could so easily give up being Indians and join the American mainstream?

You see where this thinking inevitably leads? That's why Indians claim the opponents of sovereignty are racist in their hearts. It's because Indians, unlike their opponents, have thought through the issue to its logical conclusion. They understand that giving up their sovereignty would mean the eventual destruction of their culture and race.

>> "It goes back a century to when native populations had been dispossessed," explains former California senator Pete Wilson, "to when the U.S. was largely an agricultural nation and we did not have the kind of economy we have today." <<

Pete Wilson is another well-known opponent of Indians. Not only hasn't Golab quoted a single Indian, she hasn't quoted a single Democrat. Nor any other liberal or moderate politician. Nor a single pro-gaming expert, whether Indian or not. Nor a single academic or other expert on Indian law. One rarely sees such a badly slanted article masquerading as objective journalism.

>> Most analysts concur that IGRA is a terrible law—vague, fuzzy, and unclear. <<

I've never heard any analysts say that, much less "most analysts." Until Golab names these so-called analysts, we can safely dismiss this statement.

>> "IGRA has subsequently been interpreted by the courts to mean that a state can pass a ballot initiative granting a lucrative monopoly on gambling, based solely on race, within a state that does not otherwise allow gambling...." <<

Wrong. The so-called monopoly isn't based at all on race, much less "solely" on race.

When this "analyst" refers to "a state," he means the voters in that state. That's called democracy in action. If the people don't want to give tribes a monopoly, they can vote no on the ballot initiative. Several states have done that and that's also democracy in action.

>> IGRA became a mechanism for the gambling industry to enter states where gambling had been illegal for more than a century, allowing it to operate outside the legal jurisdiction of the state governments. <<

Wrong. IGRA mandates that a tribe must sign a compact with a state before it can pursue gaming. The compact creates a legal structure for gaming-related issues. If a state wants to increase its legal jurisdiction, it can do so by negotiating it in the compact.

And recall that all tribes operate under the feds' legal jurisdiction, which provides ample protection in most cases.

>> "The groups in some cases are so marginal it's almost laughable," says one legislative analyst. <<

What's laughable is Golab's proclivity for quoting unnamed "analysts." One has to wonder if these analysts even exist. Maybe the analyst is some clerk or secretary in some legislator's office.

>> Experts contend that Congress never intended sovereign status for every parcel of land granted to Indians. <<

Which experts contend that? Congress can undo whatever it did if it's really a problem.

>> The small California rancherias, for example, were meant to host housing projects for landless Indians. <<

Hosting housing projects and being sovereign aren't mutually exclusive options.

>> "Do you really think Congress intended for them to be a sovereign nation over which state law would have no force?" asks one legislative analyst who specializes in Indian law. <<

I think Congress intended that. Who is this unnamed person to say differently? How do we know the person "specializes" in Indian law? And specialization isn't the same as expertise, is it?

It would be a lot easier to debate these insinuations if Golab named the sources for her claims. That must be why she didn't name them.

>> Scott Peterman says the Indian sovereignty problem will ultimately have to be solved by Congress, a sentiment echoed by many other observers across the nation. <<

Peterman has no credentials or credibility on Indian sovereignty issues. Golab hasn't documented much of a "problem" with Indian sovereignty. But if there is a problem, Congress has the power to resolve it and presumably will act.

>> He believes Congress should terminate tribal sovereignty definitively. <<

I believe Peterman believes that. That's because I believe he's anti-Indian.

Congress already tried terminating tribes and their sovereignty in the 1950s and 1960s. The practice failed miserably at helping Indians or alleviating their problems.

What you never hear from anti-Indian activists is how the policy that didn't help Indians then would magically help Indians now. That's because it wouldn't help Indians, of course.

Rather, termination would help the white people who are upset with Indians. These white people don't like Indians moving into their neighborhoods, taking some of their business, or professing their un-American views. Indians should be seen—in old movies and on sports teams—and not heard, according to these people.

We're still waiting for Golab to quote the first Indian on whether sovereignty helps Indians, whether termination would help them more, and what Indians really need to live long and prosper. It'll be a long wait, so don't hold your breath.

>> "The irony is, the tribes claim they need sovereignty to preserve their culture, but they use it to build casinos. <<

The irony is how thoughtless this statement is. Preserving culture costs money. Casinos generate money. Tribes are using casino money to preserve their cultures.

>> They talk about 'mother earth,' but they are more than willing to trade land for slot machines. <<

I've never heard of a tribe that gave up its present land base to gain any form of gaming. Another unsubstantiated claim.

>> Many tribal governments are so corrupt they are a bigger enemy to Indian culture than anybody. <<

Many governments are corrupt, period. This isn't an Indian gaming issue.

>> In 1998, the Court concluded that the doctrine of tribal sovereign immunity was outdated, but it also concluded that Congress, not the courts, needed to fix it. <<

Sovereign immunity is one aspect of sovereignty. It's not the same as sovereignty.

I don't know what case Golab is referring to. It may be the Hicks case. In any case, the Supreme Court has narrowed the scope of sovereignty in general and sovereign immunity in particular. That isn't quite the same as saying either one is "outdated."

>> When it comes to sovereignty, everyone seems to agree that Congress will eventually have to "mend it or end it." <<

Ending it isn't an option except for rabid, right-wing, anti-Indian activists.

>> The problem is a lack of will, due largely to ignorance or fear of the fast-growing political clout of tiny gambling-enriched tribes who have shown a great willingness to use their lucre for political donations. <<

"Ignorance"? That's funny considering the Congressional leaders who support tribes and tribal sovereignty are among the most knowledgeable people on Indian issues. They know a lot more about these issues than a few right-wing activists or one right-wing writer knows.

And "fear"? Indian tribes are proud to have made a difference in a few elections for House and Senate representatives. But tribes don't make a difference in the vast majority of Congressional elections, many of which aren't close or even contested. To say that enough politicians are scared to prevent them from voting on Indian-related legislation is patent nonsense.

House and Senate representatives routinely kill or amend or vote down Indian-related legislation. Tribes routinely get far less than what they ask for or arguably deserve. To claim they control the legislative process is another falsehood and stereotype.

"Pro-tribal forces" = democratic majority

>> Currently, nearly all Indian legislation is controlled by pro-tribal forces, particularly in the Senate. <<

This is a great job of spinning the truth. The truth is that "pro-tribal forces" means a majority of the House and Senate. The majority routinely votes down anti-Indian legislation proposed by a minority because the majority realizes it's wrong. What you're reading is nothing less than the whining of said minority when it doesn't get its way.

>> Senator Elizabeth Dole has a bill calling for recognition of the Lumbee Nation of North Carolina, and fellow Republican, Senator George Allen, is backing a measure to recognize six new tribes in Virginia. <<

So? These tribes have been seeking federal recognition long before gaming became an issue in 1988.

>> "Tribal sovereignty is going to be a hard thing to beat because the politicians are ignorant," says Scott Peterman. <<

Peterman means the politicians are ignorant of how tribal sovereignty is hurting him and his right-wing friends. These zealots want to increase their power and profits and Indians are in the way.

>> "They think sovereignty is good for the Indians, but it isn't. It's good for the tribal governments, not for individual Indians." <<

Yeah, right. When Golab quotes the first Indian who says that, then you can start considering it. Until then, the claim is worthless.

>> "That course of action cannot succeed," Alaska Senator Ted Stevens told the Alaska Federation of Natives at its annual convention in 2003. "If those villages are recognized as sovereign nations, the future of Alaska as a state is in jeopardy: Alaska would ultimately encompass a huge collection of independent tribal nations, unconnected by a state government and unprotected by the federal system." <<

Why would tribal nations in Alaska be any less protected by the "federal system" than other tribes are? The system may not work perfectly for any tribe, but that's no reason to exclude Alaska villages from it.

If the villages think it's to their benefit, it probably is. They know best what they need to succeed.

See Stevens: Sovereignty Threatens "Destruction of Statehood" for more on Stevens' anti-sovereignty position.

>> Stevens, who championed Alaskan statehood back in the 1950s and became a senator in 1968, added a rejoinder to opponents who called him a bigot for defending that line of argument. <<

Despite his rejoinder, people still thought that he didn't get it, that he was taking an anti-Indian position.

>> Some Indians insist that sovereignty is the essence of being an American Indian, so they respond to any questioning of sovereignty as a personal attack on Indians. <<

Yes...so? How is eliminating sovereignty not a personal attack on Indians? If the loss of sovereignty would affect them personally, and it would, it's a personal attack.

>> Those who question sovereignty are frequently denounced as racist. <<

Yes, and with good reason, as I've explained above.

>> Former Washington senator Slade Gorton was actually a defender of tribal sovereignty except when it trampled on non-Indian rights, and for even that mild reservation, he was branded "The Indian Fighter" and demagogued as racist, which contributed to his narrow defeat in 2000 by Maria Cantwell. <<

Golab claims Gorton was a defender of tribal sovereignty, but she doesn't offer any evidence of it. She'd have trouble quoting a single Indian who agreed that Gorton defended sovereignty.

In other words, the "Indian Fighter" label was accurate. Enough people thought so to pick Cantwell over Gorton. If a majority of people, including almost every Indian, voted against Gorton, why should we believe he was doing good? Don't Washington state voters know what was best for them?

>> Because of the volatility of the sovereignty issue, more than a dozen senators and congressmen declined to be interviewed for this story. Many of their aides who did talk asked not to be identified. <<

"Many" of their aides? Try all their aides. I've rarely seen such a lengthy screed with such a paucity of named sources.

>> "Politicians are afraid to speak out and have their views seen in print," explains one activist, "because then tribes will spend big money to get them un-elected." <<

A small minority of politicians are afraid to speak out because their views are in the minority. Taking anti-Indian positions against the majority of their colleagues will reduce their prestige and power. That's why they're afraid to speak out, in other words: because their positions are unpopular, immoral, and wrong. No one likes to be on the losing side.

>> Indeed, Indian tribes now spend more on elections than any other interest group in America. <<

Another unsubstantiated opinion.

>> "Tribal gaming has created a terrific inequality between tribes, and the people who have benefited are only a tiny percentage of American Indians," says one government official who asked not to be identified. <<

Right. Before gaming, all tribes were poor. Now some tribes are rich and the rest are poor. So what's the solution: terminate tribal gaming and sovereignty so gaming tribes can return to poverty? So they'll all be equally poor again?

>> Indeed, almost half of the nation's Indian population lives in five states—Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Oklahoma—that account for only a small percentage of Indian gaming revenues. <<

These tribes have small populations and few urban centers. They aren't prime locations for any service-oriented business. Therefore, it's not the least bit surprising that Indians in these states haven't benefited as much from gaming. They also haven't benefited as much from other industries that rely on urban locations and populations.

>> The same official is skeptical that any politician will have the guts to stand up to the Indians until everyday Americans are up in arms. <<

The same unnamed, cowardly official, Golab means. Funny that she thinks leaders who stand up for Indians—e.g., John McCain and Ben Nighthorse Campbell—are fearful but these anonymous crybabies are brave.

So politicians should stand up to the tribes who control the system but who aren't benefiting from sovereignty. By terminating these tribes, Indians will stop controlling the system but start benefiting from being just like everyone else. Does that about sum up Golab's position?