The following articles give a fairly definitive origin of the word "squaw":

The following articles give a fairly definitive origin of the word "squaw":

The following articles give a fairly definitive origin of the word "squaw":

The following articles give a fairly definitive origin of the word "squaw":

Reclaiming "Squaw" in the Name of the Ancestors

From The Cherokee Voice. Statesboro: Jun 30, 2001. Vol.27 pg. 8:

Squaw is not an English word. It is a phonetic rendering of an Algonkian word, or morpheme, but it does not translate to mean any particular part of a woman's anatomy. Within the entire Algonkian family of languages, the root or morpheme, variously spelled "squa", "skwa", "esqua", "kwe", "squeh", "kw" etc. is used to indicate "female", not "female reproductive parts." Variants of the word are still in widespread use among northeastern peoples. Native speakers of Wabanaki languages use "nidobaskwa", to indicate a female friend, or "awassokwa", to refer to a female bear; Nipmuc and Narragansett elders use the English form "squaw" in telling traditional stories about women's activities or medicinal plants; when Abenaki people sing the "Birth Song", they address "nuncksquassis", the "little woman baby." The Wampanoag people, who are in the midst of an extensive language reclamation project, affirm that there is no insult, and no implication of a definition referring to female anatomy, in any of the original Algonkian forms of the word.

[Q] From Wil Neill: "I once heard that the Early French explorers used a term that sounded like squaw in a derogatory fashion to refer to the native American females as if they were harlots. The term somehow reminded the explorers of a French word. My research has not turned up anything along these lines. Have you ever encountered such a word?"

[A] It was actually settlers in New England who first came across the word in various Algonquian Indian dialects, for example as squa, a woman, in Massachusetts dialect, or its equivalent squaws in Narragansett. It is recorded in English as early as 1634, in a book by William Wood called New England's Prospect.

Although it started out in English with the same neutral sense as it had had in its Native Indian dialects, it quickly took on negative undertones, often appearing in humorous or disparaging contexts. That is the situation that prevailed until 1973, when Thomas Sanders and Walter Peek published an anthology called Literature of the American Indian, in which they said that it "probably" came from a French corruption of the Iroquois word otsiskwa, female sexual parts, and suggested that it was therefore more insulting than anyone had previously thought. This is presumably your French connection. Their statement has been widely believed — despite that "probably" — though the early English settlers had no contact with the Iroquois, who lived a long way away, and it is extremely unlikely that their word could have been clipped to make the English squaw, even via French, a route that is highly improbable in any case. The false derivation was given wide public airing on the Oprah Winfrey television show in 1992.

As a result, the word is now widely regarded as deeply offensive, especially among those who are not native Americans, and there have been proposals, for example, to remove it from place names such as Squaw Mountain and Squaw Lake. I hold no torch for the word — as commonly used it is indeed derogatory — but suggest that attitudes to it ought to be based on evidence rather than misinformation.

As noted in these articles, there's some controversy about the origin of the word. In Respect Native Women—Stop Using the S-Word, Suzan Shown Harjo claims the word is obscene. But Cecil Adams essentially agrees with the Cherokee Voice in Is "Squaw" an Obscene Insult? He concludes the word isn't as bad as "nigger" but is as bad as "pickaninny."

A worthless word

Whatever the origin and original use of the word, it has become an insult. An excerpt from the book Jim Crow Guide to the Way It Was emphasizes how this happened:

In the opening up of Oregon to white settlement, even Methodist clergymen expressed no regret at seeing Indian women being clubbed to death and Indian babies dashed against trees by white settlers. One Oregon settler named Beeson wrote: "it was customary [for the whites] to speak of the Indian man as a buck; of the woman as a squaw; until at length in the general acceptance of the terms, they ceased to recognize the rights of humanity in those to whom they were applied. By a very natural and easy transition, from being spoken of as brutes, they came to be thought of as game to be shot, or as vermin to be destroyed."

Even if there weren't a long history of using the word as an insult, it still would be a poor choice of words. In other words, even if it weren't a slur, it still would be a stereotype. Consider the following exchange with a correspondent:

>> The word is inappropriate in places like Arizona or Michigan but in New England the word has existed, defined as "woman," for thousands of years <<

Which would suggest it's inappropriate for a regional or national audience also. For instance, "nigger" is used in some black communities and parts of the South as "normal" speech. I trust the parallels are obvious. <g>

>> The Wabanaki, Massachusset, and Narragansett all have slight variations of the word "squaw" meaning woman. <<

These tribes are, what, 1% of the total Native population? And even if "squaw" weren't inappropriate, what value does it have? Since it seems synonymous with "Indian woman," it has the effect of painting Indian women as some unusual class of women requiring a special word. It suggests they have a limited, second-class role, which doesn't include being a leader or warrior.

As Cecil Adams notes, would anyone seriously use the word "Jewess" or "Negress" in a conversation today? I'd put "squaw" in the same class—a worthless historical oddity that serves only to stereotype people.

Clarification on the derivation of "squaw"

Another correspondent disputes both Cecil Adams and the previous correspondent:

Kwé,

On your "Squelching the S-Word" page, someone wrote to you, saying that "squaw" means "woman."

This however is completely wrong.

In Algonquian languages, there is the sound at the end of words which is something like "squaw", but it is NOT a word, and can never be used as a word.

For example, in my language (Míkmaq), we have:

Nitap -- My male friend

Nitapéskw -- My female friend

Muin -- Male bear

Muinéskw -- Female bear

All it does is make a word female...but it is not a word alone, and can not be used as a word alone, for alone it has no meaning at all.

It definitely does not mean "woman." A "woman" in Míkmaq is Épit.

The very fact that the word "squaw" was used as a word for "whore" is enough to have the word abolished!

Sincerely,

Maqtewékpaqtism

==

Míkmaq Net -- http://www.mikmaq.net

MíkmaqMail.com -- http://www.mikmaqmail.com

Mawiómi -- http://www.mawiomi.com

Awókejit -- http://www.awokejit.com

==

Whew. Amazing how one word, or pseudo-word, can cause so much trouble.

I think the Cherokee Voice is correct in calling the root of "squaw" a morpheme rather than a word. It's a combining form that meant "female." Anglos heard it and coverted the fraction of a word meaning "female" to a whole word meaning "woman." Those who claim "squaw" means "woman" in Algonquian are just being a little imprecise, that's all.

Time to reclaim "squaw"?

From my e-mail:

Aboriginal women reclaiming "squaw" would be as futile as African-Americans reclaiming "nigger"

re: CBC Radio's First Voice program, 9:30 AM, Friday, July 8, 2005

(Because Carol Morin, radio host of First Voice, doesn't have an email address for that program, I had to send this message to her via her other program, CBC TV Northbeat. I hope she gets it... in more ways than one.)

The word "squaw" is an anglicized and bastardized version of the Algonquin term, "iskwew" or one of its variants. This is an important distinction. Should Ms. Morin and others wish to reclaim the latter, with its original pronunciation and associated meaning, that is, "woman", then fine, I have no objections to that. But if she or others thinks its acceptable to reclaim the former, that blunt sounding word along with its equally ugly association, which at its root is racism and misogyny, then I vehemently object, so much so that these words do not accurately portray my revulsion at the thought.

As a Cree child, I heard this demeaning slur directed toward my mother by both white people and other native people, both men and women. The word had at this time had become internalized by native men and women who felt it acceptable to call a native woman down using this term, and not because it meant "woman" either, but because it meant "whore" or when a white person used it, "a dirty Indian whore" — or some other demeaning intent.

So later in my adult life, when I came upon a lake in northern B.C. called "Squaw Lake," I worked with a prominent Aboriginal leader in B.C. to have that word removed from this province's geographical place names register. It worked to where just a few years ago the Province has since struck the name from its registry.

And so now, Ms. Morin and others are asserting that the anglicized term can somehow be reclaimed and made over into its respectful Algonquin meaning? As I said, I have no qualms with the Algonquin pronunciation and its meaning. But the grotesque anglicized version should not be rescued from the scrap heap of North American racism, misogyny, colonization, and genocide — cultural or otherwise. Bury it, along with other colonial dark age terms, such as: redskin, savage, heathen, and so on.

As I imagine this word coming to some form of "acceptability," I shudder at the thought of my young daughter using it with her female friends, similar to the way marginalized Black youth in America have taken to calling each other "nigger" or "bitch." And nevermind how this word's usage would then be picked up by native males, that is, if wasn't yet again being perpetuated by them, and, too, by persons of another ethnicity who've yet to purge their woman-hating and/or racist tendencies.

Ms. Morin may no longer live in a world of misogyny or blatant, in-your-face, racism. That's her success. Yet this blessing hasn't visited every native women or native community. Of all people, as a media practitioner, she should know that a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing, and that once her message leaves her lips, she loses control of it, along with how it will be interpretated and used by others. This topic is too big and too important for a mere 10-minute broadcast, or to simply to fill air time, or to scratch a mere musing. If it's going to be treated at all, it needs much more than what she gave it, that's for sure.

Nevertheless, I can only hope her intent for that particular topic dies, along with the use and meaning associated with that dishonourable word, "squaw." But long live "iskwew"!

Kevin Ward

Mikisew Cree

Vancouver, B.C.

The Cherokee Voice concludes its historical analysis of "squaw":

Reclaiming the Word Squaw — Part Two

[T]he word "squaw" is no longer a neutral descriptive term in modern America, and most Americans cannot tell the difference between a historical fact and a modern insult. The problem is compounded by the use of Native place names for commercial ventures — like Squaw Valley Resort, or other modern businesses — that represent the taking of tribal lands of white recreation. The solution of simply changing place names, however, carries with it the potential for erasing regional Native history. Names like Big Squaw and Little Squaw Mountain, or the many Squaw Rocks, stand as silent markers of Native American women's places and histories that have been forgotten by Native and non-Native alike. If the real goal is a preserve that history, then the solution is easy — encourage the local Native Nations to rename these places in their original languages, rather than use an English rendition of a controversial word.

More on the origin of "squaw"

The Changing Perception of the Word "Squaw"

"Squaw" in the Stereotype of the Month contest

Lego Western Chess has chief, squaw, and totem-pole pieces

Indian women are "squaws," sex objects in YouTube videos

eBay auctions Red Indian girl, squaw, Pocahontas costumes

Nunes: Illini were "a superstitious lot" of "handsome creatures"

Larry the Cable Guy tells "squaw skank" joke on Leno show

"Satire": Hooters tribe is recognized, "squaws" wear t-shirts

YouTube videos show models with feathers, face paint, bones

Maurice and Earl refers to Natives' "sacred animal," "squaw"

NY Post's New World review is headlined "Squaw Talent"

Indian woman called "squaw, "running bear," "two feathers"

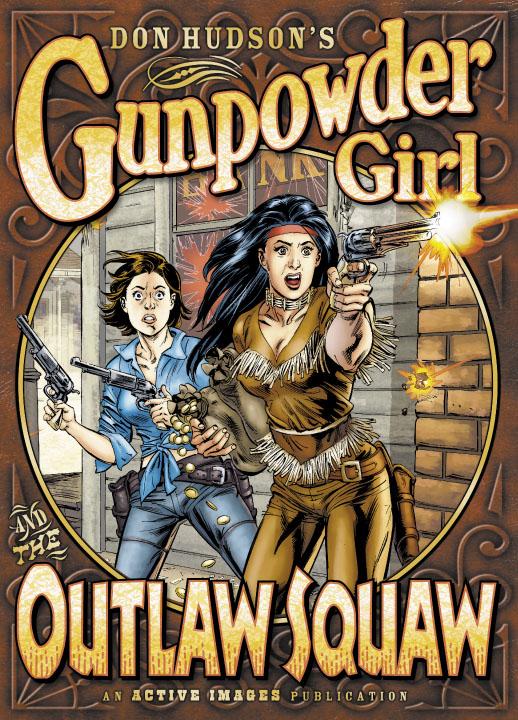

OUTLAW SQUAW stars generic buxom Indian beauty

Sketchpad suggests drawing a caveman, witch, and squaw

S.F. bar displays Native woman's teeth, calls her "squaw"

SF Chronicle headline: "Skiing Squaw, Welfare Waif?"

Swatch sells a reddish, fringed "Squaw" watch for men

Redeye comic strip uses Plains clichés, calls woman "squaw"

MsSquaw.com is proud of its politically incorrect name

"The Miccosukees can just get their squaws pregnant"

Tee Pee Campground has "squaw" and "brave" restrooms

More on "squaw"

The confounding s-word

Hottest squaw since Pocahontas?

The Squaw Peak controversy

"Squaw" on the way out

Good-bye to Squaw Peak

Nothing wrong with "squaw"?

Piestewa or Swilling Peak?

Napolitano to eliminate "squaw"?

Tough question for Squaw supporters

Piestewa or Squaw Peak?

Related links

Indian women as sex objects

Readers respond

"Reverse the principle": Have Native men refer to white women as "squaws," then wait and see how long it's deemed "a harmless and acceptable referent."

Teacher uses "squaw" as "an appropriate term for American Indians because she will not be censored in America."

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.