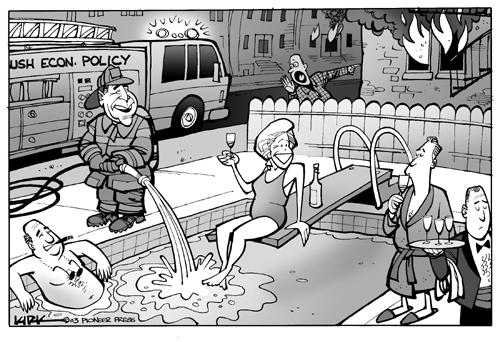

In general, economists will tell you that free-market capitalism is the best economic system. This is more a statement of faith—a philosophical or religious dogma—than a matter of fact. It's an ideology.

In general, economists will tell you that free-market capitalism is the best economic system. This is more a statement of faith—a philosophical or religious dogma—than a matter of fact. It's an ideology. In general, economists will tell you that free-market capitalism is the best economic system. This is more a statement of faith—a philosophical or religious dogma—than a matter of fact. It's an ideology.

In general, economists will tell you that free-market capitalism is the best economic system. This is more a statement of faith—a philosophical or religious dogma—than a matter of fact. It's an ideology.

History has rarely if ever seen a pure free-market system. Such a system may start "free," but freedom quickly leads to excess and manipulation and crime, so regulation inevitably arises. What economists mean when they say they favor a free-market system is that they favor a relatively free-market system. Because, again, they've never experienced a purely free-market system.

In fact, what they mean is, they favor the present US system, which is decidedly not free. Rather, it's a mix of free markets and necessary government regulation, which keeps the excesses, manipulations, and crimes partly in check. A truly free system would never work; it would be a Darwinian nightmare where the rich consumed the poor.

Our semi-regulated system has been the most successful in world history—yet they complain because it hasn't been free enough. That's the mark of a religious fanatic or ideological zealot. He takes it on faith that "free" markets are best, regardless of the evidence.

What happens when free markets get too free? The slave trade, the Western land rush (i.e., the genocide against Indians), the buffalo's near-extinction, frequent recessions and depressions (in the second half of the 19th century), oil monopolies, the Great Depression, DDT in bald eagles, thalidomide in babies, asbestos in homes, savings-and-loan failures, the dot-bomb crash, Enron-style accounting scandals, etc. One could write books, if not an encyclopedia, on the subject.

Our God-given right to take whatever we want

The environment gives us all the raw materials we have: fresh air, clean water, underground minerals, fertile fields, herds of animals. The capitalist faith begins with the exploitation of these resources and the people who own them. That suggests why indigenous cultures around the world are fighting the forces of multinational corporations—of globalization.

When capitalists exploit a resource, do they pay a fair-market value for it? Not if they can help it. As Tony Castanha explains in Delegation Fighting to Revoke Papal Bull "Inter Caetera" of 1493, 9/29/00, capitalists believe they have a God-given right to exploit whatever and whoever they want:

Today, many nation-states look to U.S. policy as a standard in their treatment of their respective indigenous populations. Given that the U.S. track record has been one of the total obliteration of native rights, is it any wonder why other governments continually repress their own people, native and non-native?

All of this of course is driven, sponsored and sanctioned in the name of multinational corporate interests, the "money god" of today. This is what the modern international system of law is about. The system is based on the "Law of Nations," which sanctioned the "discovery" campaign among Christian European nations to begin with.

Both U.S. Federal Indian law and international "corporate" law today stem from the concept of "discovery," which stems from the papal bulls, which stems from a "divine" right from god.

This God-given "divine right" is a bastardization of Christian belief, if not the negation of it. Mohandas Gandhi understood this. As Dr. Gerry Lower explains in Gandhi's Seven Root Causes: An East-West Dialectic Synthesis:

In contrast to the Mosaic Decalogue of negatives, Gandhi provided seven root causes of unfairness and injustice, all consisting of volitional human activities in the absence of socially-redeeming moral content.

Gandhi's Seven Root Causes

Wealth without Work

Pleasure without Conscience

Knowledge without Character

Commerce without Morality

Science without Humanity

Worship without Sacrifice

Politics without Principles

Here, Gandhi, speaking from the ethical east, is pointing out that most human activities are honest and just only if they are assigned a moral qualifier aimed at preserving, not law, but Christian ethics. Insofar as these moral qualifiers are not honored in human societies, we can expect to find social pathology, e.g., corruption, exploitation, and despotism. Welcome to Bush's world of religious capitalism.

Indeed, America under the auspices of Bush's religious crony capitalism can not claim to honor a single one of the dialectic (moral cum ethical) principles set forth by Gandhi. Rather, Gandhi's root causes of human misery fairly well describes the Bush administration's mindless, despotic policies and approaches in it's quest to fulfill religious prophecy.

The global religious machinations of the Bush administration have no ethical content and no moral content, only absolutist legal content aimed at furthering neoconservative dominion. Gandhi's moral qualifiers, being based upon dialectic human values, are entirely Christian in content and scope. They have no place in Bush's JudeoRoman view of the world.

Capitalism: history's biggest pyramid scheme?

As long as Nature's resources hold out, capitalists can convince themselves their economic system is perfect. If you use up a resource (e.g., buffalo herds, Dust Bowl farms), just move on and replace it. But what happens when that's no longer possible? An article in the Guardian explains:

Comment

Our quality of life peaked in 1974. It's all downhill now

We will pay the price for believing the world has infinite resources

George Monbiot

Tuesday December 31, 2002

The Guardian

With the turning of every year, we expect our lives to improve. As long as the economy continues to grow, we imagine, the world will become a more congenial place in which to live. There is no basis for this belief. If we take into account such factors as pollution and the depletion of natural capital, we see that the quality of life peaked in the UK in 1974 and in the US in 1968, and has been falling ever since. We are going backwards.

The reason should not be hard to grasp. Our economic system depends upon never-ending growth, yet we live in a world with finite resources. Our expectation of progress is, as a result, a delusion.

This is the great heresy of our times, the fundamental truth which cannot be spoken. It is dismissed as furiously by those who possess power today -- governments, business, the media -- as the discovery that the earth orbits the sun was denounced by the late medieval church. Speak this truth in public and you are dismissed as a crank, a prig, a lunatic.

Capitalism is a millenarian cult, raised to the status of a world religion. Like communism, it is built upon the myth of endless exploitation. Just as Christians imagine that their God will deliver them from death, capitalists believe that theirs will deliver them from finity. The world's resources, they assert, have been granted eternal life.

The briefest reflection will show that this cannot be true. The laws of thermodynamics impose inherent limits upon biological production. Even the repayment of debt, the pre-requisite of capitalism, is mathematically possible only in the short-term. As Heinrich Haussmann has shown, a single pfennig invested at 5% compounded interest in the year AD 0 would, by 1990, have reaped a volume of gold 134bn times the weight of the planet. Capitalism seeks a value of production commensurate with the repayment of debt.

Now, despite the endless denials, it is clear that the wall towards which we are accelerating is not very far away. Within five or 10 years, the global consumption of oil is likely to outstrip supply. Every year, up to 75bn tonnes of topsoil are washed into the sea as a result of unsustainable farming, which equates to the loss of around 9m hectares of productive land.

As a result, we can maintain current levels of food production only with the application of phosphate, but phosphate reserves are likely to be exhausted within 80 years. Forty per cent of the world's food is produced with the help of irrigation; some of the key aquifers are already running dry as a result of overuse.

One reason why we fail to understand a concept as simple as finity is that our religion was founded upon the use of other people's resources: the gold, rubber and timber of Latin America; the spices, cotton and dyes of the East Indies; the labour and land of Africa. The frontier of exploitation seemed, to the early colonists, infinitely expandable. Now that geographical expansion has reached its limits, capitalism has moved its frontier from space to time: seizing resources from an infinite future.

An entire industry has been built upon the denial of ecological constraints. Every national newspaper in Britain lamented the "disappointing" volume of sales before Christmas. Sky News devoted much of its Christmas Eve coverage to live reports from Brent Cross, relaying the terrifying intelligence that we were facing "the worst Christmas for shopping since 2000". The survival of humanity has been displaced in the newspapers by the quarterly results of companies selling tableware and knickers.

Partly because they have been brainwashed by the corporate media, partly because of the scale of the moral challenge with which finity confronts them, many people respond to the heresy with unmediated savagery.

Last week this column discussed the competition for global grain supplies between humans and livestock. One correspondent, a man named David Roucek, wrote to inform me that the problem is the result of people "breeding indiscriminately ... When a woman has displayed evidence that she totally disregards the welfare of her offspring by continuing to breed children she cannot support, she has committed a crime and must be punished. The punishment? She must be sterilised to prevent her from perpetrating her crimes upon more innocent children."

There is no doubt that a rising population is one of the factors which threatens the world's capacity to support its people, but human population growth is being massively outstripped by the growth in the number of farm animals. While the rich world's consumption is supposed to be boundless, the human population is likely to peak within the next few decades. But population growth is the one factor for which the poor can be blamed and from which the rich can be excused, so it is the one factor which is repeatedly emphasised.

It is possible to change the way we live. The economist Bernard Lietaer has shown how a system based upon negative rates of interest would ensure that we accord greater economic value to future resources than to present ones. By shifting taxation from employment to environmental destruction, governments could tax over-consumption out of existence. But everyone who holds power today knows that her political survival depends upon stealing from the future to give to the present.

Overturning this calculation is the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced. We need to reverse not only the fundamental presumptions of political and economic life, but also the polarity of our moral compass. Everything we thought was good -- giving more exciting presents to our children, flying to a friend's wedding, even buying newspapers -- turns out also to be bad. It is, perhaps, hardly surprising that so many deny the problem with such religious zeal. But to live in these times without striving to change them is like watching, with serenity, the oncoming truck in your path.

www.monbiot.com

Greed makes the world go 'round

What happens when capitalists lie, cheat, and steal to beat the competition? Nothing, unless they're caught, since capitalism is a greedy, amoral system. But lately we've caught a few capitalists breaking the rules established to keep their greed in check.

July 11, 2002

Renouncing Sins Against the Corporate Faith

By Norman Solomon

Just about every politician and pundit is eager to denounce wrongdoing in business these days. Sinners have defiled the holy quest for a high rate of return. Damn those who left devoted investors standing bereft at corporate altars!

On the surface, media outlets are filled with condemnations of avarice. The July 15 edition of Newsweek features a story headlined "Going After Greed," complete with a full-page picture of George W. Bush's anguished face. But after multibillion-dollar debacles from Enron to WorldCom, the usual media messages are actually quite equivocal — wailing about greedy CEOs while piping in a kind of hallelujah chorus to affirm the sanctity of the economic system that empowered them.

At a Wall Street pulpit, Bush declared that America needs business leaders "who know the difference between ambition and destructive greed." Presumably, other types of greed are fine and dandy.

During his much-ballyhooed speech, the president asserted that "all investment is an act of faith." With that spirit, a righteous form of business fundamentalism is firmly in place. The great god of capitalism is always due enormous tribute. Yet wicked people get most of the blame when things go wrong. "The American system of enterprise has not failed us," Bush proclaimed. "Some dishonest individuals have failed our system."

Corporate theology about "the free enterprise system" readily acknowledges bad apples while steadfastly denying that the barrels are rotten. After all, every large-scale racket needs enforceable rules. Rigid conservatives may take their faith to an extreme. ("Let's hold people responsible — not institutions," a recent Wall Street Journal column urged.) But pro-corporate institutional reform is on the mainstream agenda, as media responses to Bush's sermon on Wall Street made clear.

The Atlanta Constitution summarized a key theme with its headline over an editorial: "Take Hard-Line Approach to Restore Faith in Business." Many newspapers complained that Bush had not gone far enough to crack down on corporate malfeasants. "His speech was more pulpit than punch," lamented the Christian Science Monitor. A July 10 editorial in the Washington Post observed that "it is naive to suppose that business can be regulated by some kind of national honor code." But such positions should not be confused with advocacy of progressive social policies.

"There is one objective that companies can unite around," the Post editorial said, "and that is to make money. This is not a criticism: The basis of our market system is that, by maximizing profits, firms also maximize the collective good." Coming from media conglomerates and other corporate giants, that sort of rhetoric is notably self-serving.

It takes quite a leap of faith to believe that when firms maximize profits they also "maximize the collective good." A much stronger case could be made for opposite conclusions.

The Washington Post Co. itself has long served as a good example. A quarter-century ago, the media firm crushed striking press workers at its flagship newspaper. That development contributed to "maximizing profits" but surely did nothing to "maximize the collective good" — unless we assume that busting unions, throwing people out of work and holding down wages for remaining employees is beneficial for all concerned.

Current news coverage does not challenge the goal of amassing as much wealth and power as possible. For Enron's Ken Lay and similar executives, falling from media grace has been simultaneous with their loss of wealth and power. Those corporate hotshots would still be media darlings if they'd kept their nauseating greed clearly within legal limits.

Why "nauseating" greed? Well, maybe you can think of a better adjective for people who are intent on adding still more money to their hundreds of millions or billions of dollars in personal riches — while, every day, thousands of other human beings are dying from lack of such necessities as minimal health care and nutrition.

One day in the mid-1970s, at a news conference, I asked Nelson Rockefeller how he felt about being so wealthy while millions of children were starving in poor countries. Rockefeller, who was vice president of the United States at the time, replied a bit testily that his grandfather John D. Rockefeller had been very generous toward the less fortunate. As I began a followup, other reporters interrupted so that they could ask more news-savvy questions.

Basic questions about wealth and poverty — about economic relations that are glorious for a few, adequate for some and injurious for countless others — remain outside the professional focus of American journalism. In our society, prevalent inequities are largely the results of corporate function, not corporate dysfunction. But we're encouraged to believe that faith in the current system of corporate capitalism will be redemptive.

Free-market gurus blame everyone but themselves

Free-market faith healers refuse to acknowledge capitalism's systemic flaws. To them there's no such thing as a market failure. It must be someone's fault because a God-given system ("go forth and multiply") can't fail.

As a trenchant analysis from the LA Times, 8/18/02, explains:

The Rah-Rah Boys

There are no mea culpas from the gurus who prophesied an unending bull market. They're still cruising from one posh gig to the next.

By THOMAS FRANK

Thomas Frank is the editor of the Baffler magazine and author of "One Market Under God."

Many of the '90s icons have passed from the scene: The swashbuckling dot-com entrepreneurs have moved back in with mom, the rule-breaking CEOs are being hauled before Congress for tongue-lashings, the day-trading seniors who were supposed to "beat the pros" are thanking God that Social Security still exists. But one group remains untouched: the public intellectuals of the bull market. The writers of Dow-worshipping books and commentators who handed down daring pronunciamentos from the silicon heights are still cruising from one posh gig to the next.

If you tuned in to CNBC at any point during the long, slow meltdown of the last couple of months, you probably saw the news reader turn to a representative of Forbes magazine, formerly one of the world's most enthusiastic pushers of bull market optimism, now cast as an expert on a market in retreat. If you kept watching for a few hours, you probably enjoyed the surreal sight of James Cramer, one of the late boom's most prolific publicists, trying to feign outrage at the same forces he once cheered. And you undoubtedly gaped in disbelief when you recognized Cramer's co-host as Larry Kudlow, the hyperexuberant economist who once proclaimed from the op-ed page of the Wall Street Journal that the free-market policies of the Reagan/Clinton years were so profoundly correct that they would one day cause the Dow Jones industrial average to hit 50,000.

The Journal itself, far from showing contrition for its New Economy excesses of a few years back, recently ran a defense of the nation's beleaguered stock analysts by none other than James Glassman, coauthor of the 1999 book "Dow 36,000." In his article, Glassman argued that analysts from the big Wall Street firms are being unfairly singled out for blame by killjoys like the New York attorney general. "Every bear market requires a scapegoat," Glassman wrote, "and this time the chosen victims are stock analysts." Glassman is certainly right about the stock analysts. However guilty they are for puffing the bubble, analysts alone shouldn't be forced to bear the blame for the subsequent catastrophe. That burden should be shared—by, for example, Glassman himself, the editors of the Wall Street Journal op-ed page, Forbes magazine, Cramer and Kudlow.

Messrs. Cramer and Kudlow should, by all rights, have been sentenced to some kind of lengthy intellectual exile, required to spend the next decade in a defunded public library somewhere, reading the complete works of John Maynard Keynes. But a full year into the slow-motion crumbling of the Nasdaq, CNBC decided instead to reward these two great salesmen of the bull market with their own daily program, where their thinkings, alternately frenzied and surly, can reach an even wider audience than before.

So too with Glassman. Instead of being required to write "I will not confuse libertarian hallucinations with practical investment advice" 36,000 times, he was indulged with a seat on President Bush's 21st Century Workforce Council.

We are finally rid of the most egregious corporate swindlers of the 1990s. Why aren't the intellectual snake-oil salesmen following the dot-cons into oblivion? On the most elementary level, it's because the nation's newspapers, think tanks, magazines and TV networks have a great deal to lose were we to turn on the New Economy theorists in the manner they deserve. If the intellectuals of the '90s boom are to sink like the stock analysts and CEOs into the depths of public scorn, those newspapers and think tanks would bear the brunt too. After all, any comprehensive list of those guilty for puffing the '90s bubble would read like a who's who of American media.

Try to remember what it was like in those feverish days. Virtually everyone agreed: The stock market was a form of democracy. It was a juggernaut powered by the divine inevitabilities of Silicon Valley and the awesome assembly of the people of the globe. This was well-nigh universal stuff: Both Tony Blair and Bill Clinton were believers, as were Al Gore and George W. Bush. Small-town papers across the country carried the stock-picking homilies of the Motley Fool. Bookstores everywhere allowed you to choose between reassuring stock tips penned by the Beardstown Ladies, a set of kindly Midwestern grandmas and irony-drenched stock tips penned by the Capitalist Pig, a hip Chicago Gen-Xer. Your next-door neighbor had seen the light and was day trading from his rec room, and you were thinking about doing it too.

Another reason that so many of the hyperventilating pundits of the 1990s have proven impervious to the usual consequences of error is that generating an accurate depiction of economic life really wasn't their main function. When they told the world about the miracles of the Internet and the obsolescence of all previous economic knowledge, the public thinkers of the New Economy were interested in something else.

That something else was politics. After all, the central tenet of the New Economy faith was that the free market was the highest and most rewarding form of human existence, a notion that would have seemed transparently ideological had it not always been couched in the language of technology and in lofty phrases about the juggernaut of history and the will of the common man. The great economic commentators of the '90s didn't dissect the corporation so much as propagandize for it, looking ahead to a time when the little people would identify more with the corporation than with the government.

Again, Glassman provides the apposite example. Marveling at the great things that were to happen when we the people drove the Dow all the way to 36,000, he and his coauthor wrote, "The first change we expect is political." Just as "the crash [of 1929] was the catalyst for the modern welfare state," so an eternally rising market will have "the opposite effect. As more and more Americans gain a larger and larger stake in stocks, their views undoubtedly will shift on such matters as business regulation, taxes, antitrust policy, trade, and even foreign affairs."

Another clue to the real nature of the New Economy should have been the right-wing pedigrees of a number of its most prominent gurus. Glassman himself is a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. The banker Walter Wriston, who wrote an influential 1992 book about the wonders of the Information Age, was once one of that institute's trustees. Kudlow worked for the Reagan administration, the George W. Bush transition team and the right-wing Empower America foundation. George Gilder, the most celebrated tech writer and stock picker of the 1990s, the man who launched a thousand silicon shibboleths, came to punditry after achieving considerable fame as an ultraconservative political theorist and a speechwriter for President Reagan.

The prominence of these people and others like them were, to a great degree, unrelated to their skills as economic prognosticators. Their trade was politics, and at it they were wildly successful. Americans were indeed persuaded to roll back the regulatory state in the 1990s, to give the corporations whatever they wanted, to slash welfare, to smash the labor unions and even to (sort of) elect the most pro-corporate administration since Herbert Hoover's, headed by a man who promised to privatize Social Security.

Today, though, the picture has changed. And for most of last year's gurus, the battle has simply shifted. Now it is a matter of blame and they are on the defensive, fighting to rescue their beloved free market with even more zeal than when they were talking up the Nasdaq back in '98. The crash has brought the consequences that crashes always bring: a return of the regulatory state, demands for the end of excessive CEO pay, public anger at businessmen rather than liberal college professors and—who knows?—maybe the revival of labor unions and the estate tax. For the business class the stakes are huge, and the job that confronts their army of economic commentators is weightier than ever.

Nevertheless, they have risen to the challenge with impressive creativity, cranking out a thick smokescreen of blame evasion where they once generated a fog of prosperity without limits. Whatever happens, they argue, it cannot possibly be the fault of the market. Never mind the fact that one of the very measures taken by corporations in the '90s to ensure that market rationality prevailed—the granting of stock options to top executives—is the single greatest culprit in the present fiasco: Markets never fail. Other parties, namely government, must be responsible. "This is Washington's recession," a glowering Kudlow said a little over a year ago, "for which nothing is more to blame than the arrogance of policymakers, who refused in the first place to recognize the real sources of prosperity and then refused to acknowledge that slumping stock markets were a referendum on Washington's mistakes."

Over the last year, dozens of candidates have been unearthed and pushed forward, then abandoned out of self-evident absurdity. Kudlow, for example, blamed the antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft. Gilder blamed antitrust restrictions placed on WorldCom. Others got indignant about taxes, which are always too high, since, by definition, they are equivalent to theft, or about New York's lawsuit against Merrill Lynch. With my own eyes I watched a TV show in which business reporters blamed government policy for tripping up the good people of Enron.

A more forthright school of thought blamed the public. In good times corporate ideologues had claimed to see the majesty of the vox populi in every blip and surge of the Dow; why not simply invert that argument in these desperate days? After all, it was "the Internet enthusiasm of small investors" that caused the bubble, the Wall Street Journal's Holman Jenkins wrote recently. It was mom and pop who "bear primary responsibility for driving up stock prices of speculative businesses and causing billions of dollars to flow into the creation of assets for which there is no demand now."

My personal favorite evasive maneuver, though, is the denunciation of thought crime, of those who harbor doubt and negativity. Markets can't take criticism, apparently, especially when it comes from liberal Democrats. One would think that the gurus would keep their distance from this line of blame assessment, as it seems to suggest that the stock market is a fickle, pusillanimous institution, turning tail at the slightest sign of adversity—which can hardly be reassuring to the millions of investors being told that the market is a safe place for their savings. Yet everyone from Tom DeLay to Rush Limbaugh has been hitting this issue hard of late. Critics must be silent or prosperity will never return.

But Rush and the gang have the matter entirely upside down. America's current problems stem not from an excess of dissent but from the utter unaccountability of corporate apologists like Cramer, Kudlow, Glassman and the Wall Street Journal. What was and is needed in America is not the complete and final quieting of dissent but a vibrant counterpoint to the chorus of promoters who virtually monopolized economic discussion in the 1990s. What will prevent bubbles and manias and mass delusions and maybe even bad government is a new set of public thinkers willing at least to entertain the notion that capitalism might not always allocate goods fairly or efficiently; that markets may not always be synonymous with democracy; that voting and collective bargaining are expressions of the popular will every bit as legitimate as shopping and day trading.

Maybe market meltdowns are what happen to a country when commentary on matters economic becomes the exclusive province of business thinkers. When labor unions are systematically crushed. When dissent is divorced from matters economic or social and becomes instead a quality of middle-class taste preferences, of "extreme" cars and "radical" packaged goods. When management theorists take it as their duty to dazzle us with a crescendo of free-market worship. When leaders of left parties cleanse their ranks of laborites, of New Dealers, of Keynesians, of socialists. When newspapers refuse to open their columns—on grounds of laughable, self-evident dinosaurdom—to doubters and second-wavers and old-school liberals.

Today we are paying for each of these, for all of the ways in which we expunged the common sense of our parents' America from our lives. With each month's nauseating returns, we are making good the intellectual folly of the last 10 years.

Copyright 2002 Los Angeles Times

More on capitalism as a faith

The Old Spin on the "New Economy" (7/18/02)

Related links

Government gives, free markets take

Corporate culture: rotten to the core

Globalization: exporting the American way

America's culture wars (economic)

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.