Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

Native Plays and Other Stage Shows

(5/1/07)

Two-woman Native sketch comedy

Two-woman Native sketch comedy

Bringing trickster tales to life

Native theatre festival in NYC

Anti-tobacco talent show

Raven's Radio Hour

Aboriginal playwright teaches Indians

Preview of Salvage

Some thoughts on Caliban

Unto These Hills closes

Three plays about two worlds

Upcoming drama at the Taper

Shakespearean Indians

Sacagawea the musical

Variety reviews Ishi play

The Indian and the White Guy

Hiawatha sails into sunset

King Lear with Eskimos

Review of Ishi play

Chickasaws renovate theater

Gay theater does Ishi

Romantic play in West Virginia

Roanoke play must go on

Native Voices takes Australia

Native playwrights express themselves

Indian actress in Broadway hit

Play comments on globalization

Navajo boarding school play

Hopi puppet shows

WagonBurner Theater Troop

Young Native Voices

Review of Teaching Disco

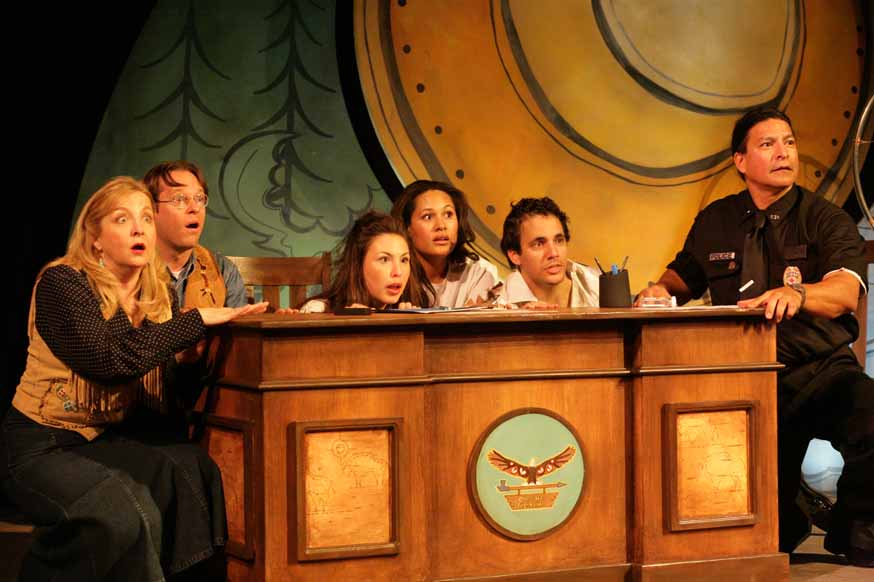

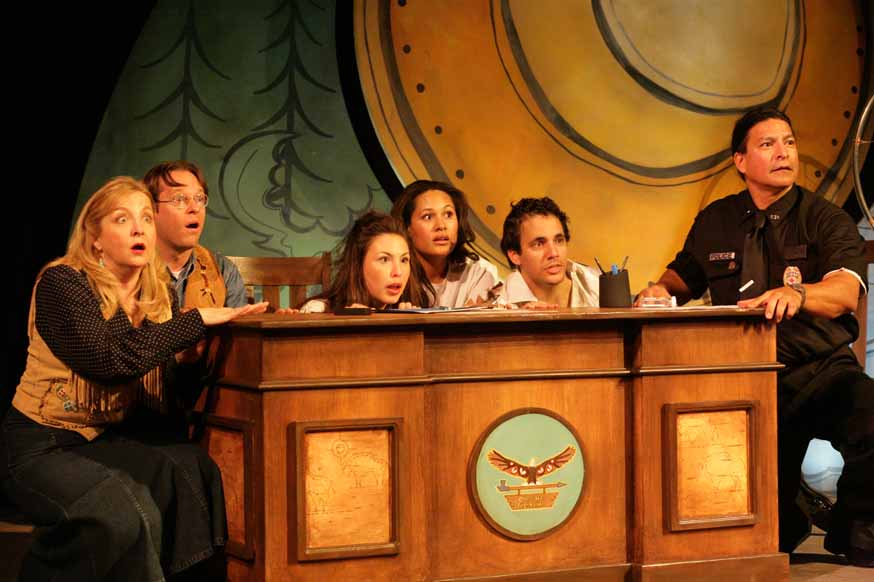

Pix of Teaching Disco

Dances with teen angst

Lakota teens dance troubles away

Native firebrand is artistic force

Studi's one-man show

Shakespeare, Aleutian-style

Breakout comedy duo

Musical comedy about Jackson

Arctic similar to Sahara

NAACP protests Ten Little Indians

Ojibwa teens put on a show

Five plays at festival

Looking for an authentic Indian

Playwright started as Navajo tooth

Tohono O'odham in immigration play

Hotbed of Native theater

Play about Cherokee hero

Indian Blood hits the road

"Sacagawea" retires

Indians learn about Indians

A Penobscot in Paris

No conflict in Yellow Robe's dramas

Sex and scheming in Taos

Shakespeare's Native play

Audiences weep over Greene

Right approach to Native theater

Non-Indian performs Ponca story

Reality show within a play

Taos version of Dangerous Liaisons

"Super Indian" on the Web

Graham Greene as Shylock

Beach family tackles suicide

Merchant of Venice trailer

Black Indian storytelling theater

More Native plays

More Native theaters

From satire to Shakespeare

What's an Indian Woman to Do?

Video of Peltier play

Peltier play on the move

Blue Jacket a white man?

All about Native Voices

Ohio plays feature Indians

Ramona remains relevant

Oldest stories get staged

Native Voices on MySpace

Everyone loves Hiawatha

My take on Berlin Blues

Omaha kids hit Broadway

Pix of The Berlin Blues

Review of The Berlin Blues

Trickster: the musical

More on Peltier play

Play of Prison Writings

Another review of Wakonda's Dream

Review of Tlingit Macbeth

Review of Ponca opera

Macbeth in Tlingit

Opera opens in Omaha

A month of plays

Super plays debut

The plays are the thing

Super diva

Plays preserve culture

"Super Indian" poster

Update on "Super Indian"

"Super Indian" premieres

Greene tackles Merchant of Venice

Another review of Indian Blood

An Indian off-Broadway

A leading Indian playwright

Some articles on William S. Yellow Robe Jr. and his plays:

Funny, it doesn't look like a social commentary

01:00 AM EST on Friday, January 28, 2005

BY CHANNING GRAY

Journal Arts Writer

A shaman who likes to take a nip, a shameless huckster hawking tourist trinkets, an acerbic poet, a "half-breed" student. All characters — real but fictionalized — in William S. Yellow Robe Jr.'s Better-n-Indins, which is getting its first full showing at Perishable Theatre this month and next.

The play, which has been in the reading and workshop stage for some time, deals with misconceptions about, even the total ignorance of, native Americana.

Using a revolving set and a generous dose of humor, Yellow Robe, who appears as a sort of emcee, leads us through a museum of changing exhibits that debunk stereotypes and poke fun at Indian ways.

Nick Bear, as Greg Jones, shows up at a powwow in an outfit that looks more like a Christmas display from Wal-Mart, with lights and all.

The play, in other words, is a series of fast-paced vignettes, some of which hit the mark, and others which fall wide of the target and seem pretty amateurish.

TWO YOUNG WOMEN meet at a powwow. Krista Weller as Nina Paints the Sky has lost her husband and kids in a car wreck. She takes self-conscious Janelle Tibs, played by Marcella, under her wing and, by placing an eagle feather in her hair, gives her the confidence to dance.

At the end of the skit, it seems Weller, too, might have died in the car accident, and was in fact a beneficent spirit looking to help a troubled sister.

The dialogue is thin, as Marcella explains how, as a Goth teen from the city, she doesn't fit in. And the acting is none too strong.

That is one of the drawbacks of this production, that most of the cast — almost all newcomers to the Perishable stage — is marginal at times.

The play, for example, could have done without the section where Weller and Marcella play two bickering schoolgirls, with Weller insisting how she may not look like an Indian but is a half-breed from the Delaware nation.

The skit tries for a "funny you don't look Indian" routine, but breaks down into some inane conversation.

TOM BUCKLAND, who is otherwise the technical director at Trinity Rep, stands out as the fast-talking proprietor of Sacred Sam's trading post, and, in one of the funniest skits of the night, really shines as the host of a game show in which contestants are shown pictures of people and have to guess whether they are Native Americans. Losers get a broken treaty that strips them of their rights.

Again, the idea is that you can't tell Native Americans by how they look (kinky hair, blue eyes), although this time the subject is handled in a much more clever, amusing way.

Buckland is a hoot as the host, with sidekick Shiny Wolf, played by Bradley Thoennes, another solid comic presence. Buckland's got the mannerisms, the inflections down cold.

At Sacred Sam's, Buckland sells brown contact lenses so tourists can look like Native Americans. There's brown, dark brown and "how much peyote have you eaten" darkest brown.

THOENNES AND BUCKLAND turn up again together as two white agents from the Bureau of Indian Affairs trying to figure out a way to apologize for all the government has done to wrong Native Americans. After failing to come up with the right spin, they decide they'll get a Native American to do the apologizing for them.

Yellow Robe, in his role as narrator, introduces the episode by explaining that at one point the BIA employed no Native Americans in its higher ranks, only as janitors and the like.

Yellow Robe, playwright in residence at Trinity Rep and a member of the Assiniboine Tribe from Montana, speaks from authority. He said he applied for a job at the BIA.

Occasionally the play, directed by Bob Jaffe, is sprinkled with what appears to be autobiographical information such as this. At one point, Yellow Robe tells how his grandfather as a boy was packed off and sent to live 1,000 miles from home, presumably at a government school, until he was of legal age.

Between vignettes a voice comes over the PA system announcing things like, "It is now 8 p.m., are you sure the person sitting next to you is not native?"

Otherwise, Better-n-Indins is something of a kaleidoscopic undertaking, more a series of scattered impressions and snappy one-liners than a single arching story.

The thing is, Yellow Robe's self-depricating humor many a time saves even the weaker moments. It's a funny, sometimes touching play that's worth a look.

Better-n-Indins runs through Feb. 26 at Perishable Theatre, 95 Empire St., Providence. Tickets are $20, $15 for students and seniors. Call ArtTix at 621-6123.

*****

From TwinCities.com:

Posted on Thu, Sep. 22, 2005

Where American Indian meets African-American

BY DOMINIC P. PAPATOLA

Theater Critic

Penumbra Theatre Company and playwright William S. Yellow Robe Jr. have put a lot of weight on the shoulders of the first show of the theater's new season.

Playing in St. Paul, the world premiere of "Grandchildren of the Buffalo Soldiers" aims to address the sometimes contentious but inextricably linked relationship between American Indians and African-Americans. And when it goes out on the road as part of Penumbra's first-ever national tour, the goal of the play is nothing less than to help Indians claim their voice and tell their own stories through theater.

The story of "Grandchildren" — a tale of a wanderer who returns home to the reservation for the naming ceremony of his young niece — shares some biographical details with that of its author. Yellow Robe, born and raised on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in Montana, claims both Assiniboine and African-American heritage.

Like other descendants of marriages between Indian women and "Buffalo Soldiers" — black soldiers who were assigned to the west in the years after the Civil War — Yellow Robe endured racism from all sides. His play addresses what it means to be an Indian, what it means to be a warrior, what it means to live in a culture within a culture.

Though Yellow Robe has been addressing these issues as a playwright for 20 years, it's been difficult to break the message out to mainstream audiences. He knows of no major Indian theater companies in the country and said most plays on the subject of his people are "either historical dramas or magical mystery tours," with Indians portrayed as mystics or seers.

"Grandchildren of the Buffalo Soldiers," is, instead, a contemporary, earthy, warts-and-all look inside a community, written with an undeniably strong sense of voice from that community.

On the surface, it might seem an unlikely production for Penumbra. But artistic director Lou Bellamy insists the play's issues of familial struggle and intercultural racism put "Grandchildren" squarely into Penumbra's wheelhouse and give the theater a chance to see through new eyes.

"Black folks," he said, "have always had to deal with the hybridity of their race — whether that's skin color, hair texture, names — and there's always been a link between many black people and native culture. A number of black writers have written about that coming together, but not many native people have."

The production has been a leap of faith. Bellamy, Yellow Robe said, is one of the few directors he's ever worked with who approached the work with enough humility to say, "I don't know, but I'm willing to learn."

Working on the play has prompted some cast members to examine their own histories. Longtime Penumbra company member Jim Craven plays Craig Robe — the character that most closely stands in for the playwright.

"I've always known that my great-grandmother was Kiowa Indian," Craven said, "and I've had bits and pieces of cultural understanding of that part of my history. But I never paid much attention to it. As an actor, I just used it when I needed it."

But as part of his preparation for "Grandchildren," Craven traveled West to walk where the Buffalo Soldiers walked. Though the weeklong trip mirrors his character's journey only in miniature, he says, "it opened a window to a huge passion that I have to bring to this role."

"Grandchildren of the Buffalo Soldiers" is being co-produced with Trinity Repertory Company of Rhode Island, and, following its performances at Penumbra, will tour to cities, college campuses and reservations across the country.

Yellow Robe acknowledges the inherent limitations of the play. Noting that the Indian community is no more monolithic than any other cultural subset, he concedes that "This is not the quintessential play for all native people, and what I know is hard to translate into the mainstream."

Still, both he and Bellamy expect the unvarnished candidness of the play will generate reactions both positive and negative. They hope those reactions are strong enough to encourage others to come forward with their own stories and tell them in their own ways.

"We have to take ownership of our voice," Yellow Robe said, "and that's what we're trying to do with this tour."

Theater critic Dominic P. Papatola can be reached at dpapatola@pioneerpress.com or at 651-228-2165. What: "Grandchildren of the Buffalo Soldiers"

When: Opens Friday, runs through Oct. 15

Where: Penumbra Theatre Company, 270 N. Kent St., St. Paul

Tickets: $32

Call: 651-224-3180

*****

Identity war

'Buffalo Soldiers' play confronts the struggles of families with mixed heritage

Thursday, November 10, 2005

"I'm a large man. There's no way I can hide," says playwright William Yellow Robe. "When you're in a classroom and you're dark and 18 other class members are all white, there's no way you can hide."

Yellow Robe's never really been interested in concealing his identity, formed partly by his mix of American Indian and black heritage. But the road for him and others born into multiethnic families can be difficult.

You're not black enough. You're not Native enough. You don't fit.

These are the struggles of Craig Robe, the protagonist of Yellow Robe's latest play, "Grandchildren of the Buffalo Soldiers," who returns to his tribe's reservation in search of community. As descendants of an American Indian woman and a buffalo soldier, the Robe family has struggled for acceptance in their tribe and with one another.

The play, being staged tonight and Friday at the Lied Center, asks audiences to consider issues of racial and cultural identity, particularly among mixed-heritage families, which, incidentally, are increasing in Lawrence. According to statistics released this year by Lawrence Public Schools, the percentage of multiethnic students in local elementary schools far outpaces those in junior highs and high schools.

"When an audience comes in there, hopefully they might be able to find themes or issues or characters or dialogue that they can identify with," Yellow Robe says from his home in Connecticut. "I hope there are some audience members who like it. And then I hope there are audience members who hate it so much that it will encourage them to write their own play.

"What's happened within indigenous literature is that our voice has been appropriated by non-Natives, and we allow them to do it. But there comes a time when we have to be able to express our own voice and to maintain our own voice."

'Walking one path'

Yellow Robe, who serves as a guest faculty member at Brown University and other institutions and who has written more than 10 plays about Native issues, penned "Grandchildren of the Buffalo Soldiers" at the request of his ailing wife. Before she died, she asked him to write a show that went beyond the typical racial dichotomy.

"The whole issue of 'breed' was always boiled down to an issue of white and native," Yellow Robe says. "They never saw the idea of someone being part Native and African-American or part Native and Asian American, part Native or Latino American. In other words, we were never really accepting the fact that we now had relations with the world."

Personally, Yellow Robe has always been pretty sure where he stands. He was raised to be Assiniboine, first and foremost, without denying the three-eighths African-American blood in his veins.

"Part of the problem is that there is this belief of being caught in two worlds, but you've got to pick one," he says. "The logic behind that is if you're jumping from one path to another path, you're not really walking one path.

"The play talks about being able to love and respect those aspects of your life and not to hide them and to lie about them."

Yellow Robe left the Fort Peck Indian Reservation when he was 18 to attend Northern Montana College. He remembers "major problems" there with Native and white relations, and he says things got violent on occasion. But he's moved on.

"You get to that point where the anger wears off," he says. "The most important thing is you don't forget. I always tell my students even if a person has a BA, MA or Ph.D. doesn't mean they have enlightenment."

Local ties

Twenty years ago, Yellow Robe says, very little was widely known about the buffalo soldiers, so named by American Indians, who thought the black soldiers — with their dark, curly hair — resembled the regal animals.

"Now it's the catchphrase of historians," he says.

In 1992, Colin Powell, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, spearheaded a movement that ended in the erection of a buffalo soldiers memorial at Fort Leavenworth, where one of the regiments of black soldiers began in 1866.

But the relationship between these soldiers and Native people hasn't been explored much, he says. Nor does the play take a historical look at that interaction. But a tie exists between issues in the show and the past in this area.

"We have a similar situation that happened right here in Leavenworth," says Phyllis Bass, director of the Richard Allen Cultural Center in Leavenworth.

It seems the oldest recorded black family in the city descended from a black militiaman and his Cherokee wife.

"Her father and brother tried to prevent him from taking her off the reservation," Bass says.

Nevertheless, the couple arrived in Leavenworth on horseback in 1855, and she never went back to the reservation.

Yellow Robe and the cast of "Grandchildren" toured the museum and gave a talk there on Tuesday. A buffalo soldier exhibit is on display through Monday in the Lied Center lobby.

Cleansing experience

Despite its reference to the buffalo soldiers — revered by some for fighting for their country and reviled by others for killing American Indians — the play really confronts contemporary struggles.

"I've always been amazed that when we perform in different communities, some community members will come up to me and say, 'You know that's exactly what happened to my son' or 'That's what happened to my nephew' or 'That's the very issue that I'm having problems with now,'" Yellow Robe says.

In this way, he says, "Grandchildren of the Buffalo Soldiers" has value for everyone.

"It is about a young man who returns, but it's not about racial identity; it's a question of humanity," he says. "He comes back to clean his heart — a heart that's been contaminated by racism, stereotypes, myths and misconceptions.

"So this man goes through this process of trying to cleanse himself of all these poisons."

Who among us doesn't have some poison to shed?

*****

Playwright discusses biracialism

By Ashley Zuzek, The Dartmouth Staff

Published on Wednesday, January 18, 2006

William S. Yellow Robe, Jr., author of the play "Grandchildren of the Buffalo Soldiers," discussed the psychology of racial duality during a Tuesday night discussion at the Hopkins Center and emphasized the need for Americans of mixed blood to identify with a single race rather than getting lost between the two.

Having mixed blood, Yellow Robe said, "has created a psychology that no one has dealt with. People go into this panic of being too native or not being native enough."

Yellow Robe, who is both Native American and African American, described the difficulty of being biracial during his discussion, "Claiming Our Relations."

While Yellow Robe identifies more with his Native American ancestry than his African American ancestry, he is not ashamed of his mixed race.

"I honor it and I never deny it," he said. However, he cautioned that people of mixed race should not "straddle both paths," and that he has never regretted identifying with his Native American side.

Yellow Robe's play, which will be performed in Spaulding Auditorium on Thursday, addresses this difficulty by showing characters who are "struggling with humanity" rather than defining themselves by the color of their skin.

"What the play does more than anything else is expose hatred," Yellow Robe said. "You can't really heal yourself until you know that you're wounded."

Yellow Robe drew upon his own experience as a mixed-blood Native American to create the play. Living on a reservation until he was 18 years old, Yellow Robe learned by interacting with other Natives that his racial identity significantly influenced his view on life.

"Even though we were from the same tribe, our perspectives were so different," Yellow Robe said about his conflicts with a white and Native American friend.

Although being biracial makes the formation of one's identity difficult, Yellow Robe said that it has also offered him the opportunity to represent the people of his tribe.

"You've got to stand up and speak for yourself so you can speak for your people," Yellow Robe said.

Yellow Robe discussed not only the uniqueness of having mixed blood but also the importance of maintaining one's identity. Through colonialism, he said, people have modified their cultures to make life easier without thinking of the consequences.

In a different vein, Yellow Robe read several poems to the audience about his wife, who passed away of breast and liver cancer. One poem, entitled "Prep Work," particularly emphasized Yellow Robe's Native American philosophy because it stressed the importance of release by encouraging his wife to "Just let go."

Yellow Robe's diverse discussion of racial issues had both personal and wider implications.

"He was dealing with a lot of concepts that have been left out of the historical explanation of this country," said James Novakowski '09, who first encountered Yellow Robe in his Native American Studies class. "I even felt resistance to some of the things he said. It was interesting to listen to him and to observe my own reactions."

The discussion, while centered on Native American and African American relations, also applied to other ethnicities.

"I thought a lot of the conflicts he mentioned for America are the same as those for China," Erin Gu '09, who was raised in China, said. "It's always a question whether you are too resistant to westernization and therefore not advancing technologically. It may shed light onto some of our problems and make the transition easier."

Related links

Free downloads on Natives in plays

TV shows featuring Indians

The best Indian movies

Comic books featuring Indians

* More opinions *

|

|

. . .

|

|

Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.

Two-woman Native sketch comedy

Two-woman Native sketch comedy