An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay :

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay : An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay :

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay :

In June, TNT debuted Steven Spielberg's Into the West. Here's the lowdown on this blockbuster mini-series:

The premise

A sprawling, multigenerational drama spanning the years 1825 to 1890, it recounts the great Western migration through the stories of two families -- one settler, one Native American -- and the ways they clash and coalesce over the decades.

Along the way, the characters participate in a remarkable range of historical events: gold rushes, the building of the transcontinental railroad, the founding of the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, the Sand Creek Massacre, Little Big Horn, and Wounded Knee.

David Hiltbrand, Spielberg Goes West, Philadelphia Inquirer, 6/8/05

Background and previews

Buffalo News: TNT Miniseries Takes Viewers 'Into the West'

Washington Post: An Unsettled Frontier: Steven Spielberg's Six-Part Epic Chronicles Clashing Cultures and the Rush to Riches

Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel: Finding the True West: TNT's New Miniseries About 2 Families Rides High on Details

Philadelphia Inquirer: Spielberg Goes West

Rocky Mountain Times: Tale of Two Families: TNT's 'West' Epic Not Typical Cowboy-Indian Fare

Washington Post: TNT Series 'Into the West' Spans 65 Years

University of Redlands Daily Facts: A New Frontier Fable: TNT's 'Into the West' Aims for an Epic -- and Honest -- Treatment of America's Expansion

The good

[L]audable aspirations are only a small part of the appeal of TNT's 12-hour, six-part miniseries (only the first six hours were available for review), produced by Steven Spielberg. Into the West boasts an enthralling story, a cavalcade of stellar performances, captivating cinematography and ambitious directing by a half dozen well-credentialed veterans, each of whom helms an episode.

Tom Jicha, TNT Marches Into the West with Gritty, Spectacular Chronicle of Pioneer Life, South Florida Sun-Sentinel, 6/5/05

Judging by the first six hours, the stunning spectacle is an engrossing, well-cast adventure story that observes historical moments, Forrest Gump-style, within the fictional family sagas.

Joanne Ostrow, A Western Magnum Opus, Denver Post, 6/6/05

The film's reach wildly exceeds what it is able to grab hold of, and its leading characters tend to be one-dimensional repositories of national virtues rather than believable human beings.

But that's the way it is in the action-adventure language of hero quests and journeys of passage. The energy of the saga comes from the larger-than-life archetypal images it presents and the way in which they tap into shared memory and the collective unconscious. Into the West consistently goes for that deeper psychic connection with the audience and achieves it often enough to promise one of the more elevated viewing experiences of the summer.

David Zurawik, Miniseries Worth the Time, Baltimore Sun, 6/9/05

Sometimes, like the pioneers, it sets goals for itself that it's incapable of achieving. But when so much current TV content merely copies from successful shows, a series that seeks something more should be applauded for its failures as well as for its successes.

Robert Philpot, Unsettling America, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 6/10/05

It has its big, entertaining heart in the right place.

Mike Duffy, Spielberg Looks to the West, Detroit Free Press, 6/10/05

It's not a masterpiece but worth watching.

Mike McDaniel, Get Ready to Settle In for Into the West, Houston Chronicle, 6/10/05

The bad

At times, the miniseries seems more like an episode of soap opera. The families suffer throughout their lives, losing loved ones to extreme circumstances. Characters come and go so quickly that viewers are not given time to become attached to them, thereby lessening the impact of the tragedies.

Laura Urbani, Numerous Characters Clog Sanitized Miniseries, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, 6/5/05

The writers are unable to carry the miniseries' generational scope. Relationships develop, shift and end offscreen. One woman falls in love with her kidnapper. Another seems to be a broodmare, a new baby popping up with almost every appearance.

Mark A. Perigard, How the `West' Was Lost: Spielberg's Western Saga Is Full of Holes, Boston Herald, 6/7/05

They say the road to hell is paved with good intentions. In the case of "Into the West," an ambitious, well-meaning miniseries about manifest destiny, genocide and race relations in the American West, it feels more like the road to boredom. By the time you get to the end, you may feel as if you've been stuck on a wagon train from Missouri to California.

Alan Sepinwall, Bland Characters Make Pioneer Saga Boring, New Jersey Star-Ledger, 6/9/05

Into the West never rises to the level of story; it's a series of vignettes strung together with extraneous, clunky voiceover, the above example of which is not the most egregious by far. It's impossible to care about the characters any more than one cares about the "re-enactors" in those anesthetized public-television dramatizations -- soap-operatic twists a la Ciderhouse Rules notwithstanding.

Elaine Wolff, We Know Drama (and This Ain't It), San Antonio Current, 6/9/05

Wearing its obviously thorough research on its buckskin sleeve — this is a show, one might say, ripped from the pages of history — and as scrupulous as it can be within its small-screen means, the series is a victim of its own ambitions. In rushing around to cover the many bases of life on the frontier, over a period of 65 years — we are continually being kicked two years, six years into the future, by narration or title card — neither the characters nor the pieces of history they represent are deeply explored. Earnest without being terribly enlightening, full of action but dramatically inert, it's like a very long, expensive, semi-star-studded educational film.

Robert Lloyd, Feast for the Eyes, Famine for the Ears, Los Angeles Times, 6/10/05

The TNT western works so hard at compressing history into a family melodrama that it forgets to fill out the family members.

There are lots of cameos, but no characters anywhere near as compelling as Ian McShane's Al Swearengen on "Deadwood" or Robert Duvall's Gus McCrae in "Lonesome Dove." TNT forgot to heed the warning of one of the series's protagonists, Jedediah Smith (Josh Brolin): "The West is a place on the map; it's not a way to be."

Alessandra Stanley, An Old West Saga, Told From Both Sides, New York Times, 6/10/05

The writers of "Into the West" care more about drawing moral lessons to punish greed and reward spiritual growth than crafting believable psychology for their creations.

Kay McFadden, Noble Intentions Can't Save Spielberg's "Into the West", Seattle Times, 6/10/05

[T]his is television, not a classroom. If you need visual aids to figure out who's who only a few hours into a television series, it may not be worth watching again (and again).

Melanie McFarland, 'Into the West' Manifests Itself as Shallow 'Roots', Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 6/10/05

Said to be the largest production ever undertaken by TNT, produced in association with Dream-works Television and executive producer Steven Spielberg, it is also a lavish yawn. In the first six of its 12 hours, one can hunt in vain for some new revelation regarding the glories and hardships of America's mythic frontier.

Sid Smith, Lavish Production Doesn't Save 'West', Chicago Tribune, 6/10/05

[A]fter three episodes, the saga is not deeply affecting. This may be because we've seen it all before in previous landmark miniseries such as "Lonesome Dove" (1989) or "Roots" (1977) or even the 1990 feature film "Dances With Wolves" — stories that created unforgettable characters who immediately drew us in and held on to us for the duration. "Into the West" at times creates mere sketches of characters, and of history, along the road to the conclusion. How many more brave faces will come and go before this series ends?

Miriam Di Nunzio, 'West' Side Stories, Chicago Sun-Times, 6/10/05

At times, "Into the West," with its stiff narration, comes dangerously close to evoking the central-casting aesthetic of an educational film. You know, something a teacher might screen in the AV room as summer rolls around and the kids are getting antsy. Something that's good for you, and politically correct as it tries to honor Native American visions and language, but something that's not necessarily engaging.

Matthew Gilbert, A Mild Look at the Wild West, Boston Globe, 6/10/05

A scatterbrained amalgam of sketchy writing, choppy editing and politically correct clichés, Into The West sets new standards for TV superficiality and bloat. It's hard to imagine that a single work can cover everything from the Gold Rush to the Civil War, the Pony Express to the transcontinental railroad, and still manage to be so utterly uninteresting.

Glenn Garvin, An Epic Story Reduced to Tedium and Clichés, Miami Herald, 6/10/05

The Indian aspects

In the era of political correctness, there has been an over-correction in evolving Indian portrayals from uncouth, bloodthirsty savages to noble individuals with a degree of wisdom and sophistication beyond plausibility. Into the West avoids this. Indians are portrayed as having a well-developed culture, steeped in family and respect for tradition. However, the script also gives them a ferocious aspect, indiscriminately killing, raping and enslaving members of rival tribes well before the white man's incursion into their world.

Tom Jicha, TNT Marches Into the West with Gritty, Spectacular Chronicle of Pioneer Life, South Florida Sun-Sentinel, 6/5/05

William Mastrosimone ("Extremities") wrote the overall story for the series and scripted three of its installments. His aim was to convey "what was the ordinary Indian doing on a daily basis," in a way that previous Westerns have missed. He said his unconscious mind helped him get there.

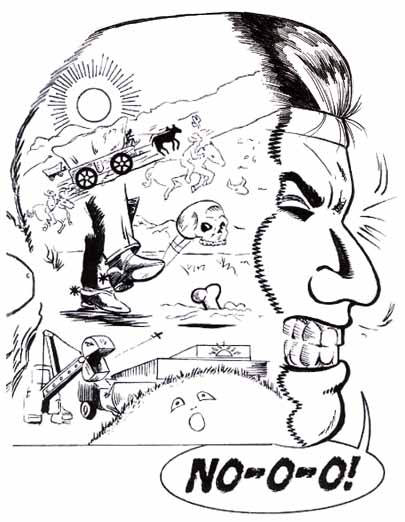

On the eve of his pitch session, when he was out of ideas and about to abandon the project, Mastrosimone had a dream.

"I saw two wheels suspended in the air before me, a wagon wheel and medicine wheel," he recalled. "I woke up three hours later and I knew it was important, but I didn't understand the meaning."

Research helped him appreciate that "the two wheels are antipodes. The Indian wheel is their almanac, their Bible, their calendar, so many things." The four quadrant lines within the wheel represent the values of courage, fortitude, generosity and wisdom; each individual is born with one value, and it is his task in life to seek the other three. "It is about balance and stewardship of the Earth," he said.

By contrast, the white man's wagon wheel is "the product of science, mathematics, metallurgy, it is the wheel of progress, what got us from coast to coast. It is dynamic, representing the belief that tomorrow is better than today."

Following Spielberg's directive to tell parallel stories about the two cultures, Mastrosimone translated the wagon wheel into a family of wheelwrights.

"I didn't want a parallel family of shamans; I thought that was too pat," he said. Instead he created the story of an Indian boy who becomes apprentice to a shaman who builds the medicine wheel. That boy is charged with the lifetime task of trying to find a way to overturn the prophecy, made in 1560, that the buffalo would vanish and the native people would be forced to live in square houses.

By the final two hours, as the Indians struggle in defeat, they turn their focus to the medicine wheel's value of fortitude, also known as "the grandmother's road."

Joanne Ostrow, A Western Magnum Opus, Denver Post, 6/6/05

Himself once a restless son growing up in North Carolina, the 35-year-old Settle easily identified with Jacob's urges to head West _ and made his own such odyssey (albeit after a few years' detour to New York to start his acting career).

Then, making this film, he sampled Jacob's revelations.

"What I learned was the degree of sacredness that the Lakota people had in everything they did, in every aspect of life," says Settle. "That's something we can use in our modern culture." He laughs. "Maybe a few less Humvees and a few more Priuses."

For the 27-year-old Carmelo, playing Thunder Heart Woman "was like coming come."

A California Mission Indian who counts herself a descendent of the original residents of Los Angeles, she grew up performing in an American Indian dance troupe led by her mother, Virginia Carmelo. Branching out into acting during college, she has since appeared in theater productions and independent films.

"I grew up like an urban Indian," says Carmelo, and when she won her role in "Into the West" she found "my understanding of what it is to be a Native American today helped me a lot to understand the native culture back then."

Frazier Moore, TNT Series 'Into the West' Spans 65 Years, Washington Post, 6/8/05

Judging by episodes 1 and 2, not very damn exciting at all. Watching Into the West is like taking your vitamins without water. TNT has produced a number of post-Manifest Destiny Western specials and they begin here with an admirable idea: to tell the story of the clash between Euro-American expansion and Native American culture with equal respect for the Native Americans' point of view and values. To do so, they enlisted a team of advisors that included a professor from Oglala Lakota College and George P. Horse Capture, senior counselor to the director and special assistant for cultural relations at the National Museum of the American Indian. Why then do the meticulously (and, I imagine, expensively) recreated scenes play so awkwardly? Even the actors who portray Lakota tribespeople don't seem to be entirely convinced of their own authenticity. Part of the fault lies with the filmmakers who decided that these scenes require more narration than the all-white scenes. The unintentional effect is to make the Native Americans seem childlike and deserving of patronization.

Elaine Wolff, We Know Drama (and This Ain't It), San Antonio Current, 6/9/05

Throughout, there is a studied effort to flip television western clichés: The first alcoholic beverage served is not a jug of "firewater" whiskey, but an Indian drink that a tribe in the Montana Territory offers a gang of quickly intoxicated pelt traders. (Later, of course, the treacherous hospitality is reversed: white traders pay Lakota hunters in whiskey, not guns.)

"Into The West" is deeply respectful of the Indian experience -- the characters speak in indigenous languages, which are translated in subtitles -- but the tribute to the Lakota turns out to be mostly stifling. Most of the tribal conversation consists of dire predictions of doom at the hands of the white invaders; the individual personalities remain as noble and static as the chief in the 1971 anti-pollution ad featuring the "crying Indian."

Alessandra Stanley, An Old West Saga, Told From Both Sides, New York Times, 6/10/05

The main thread of the story follows the lives of Jacob Wheeler, a young man from Virginia who heads West in 1825, and an Indian youth named Loved by the Buffalo, who discovers that he has powers of divination and is destined to help preserve his people's way of life. The sections dealing with the Indians are by far the most compelling (and the best acted). There are fascinating glimpses into their society, chiefly among the Lakota-speaking Sioux, whose daily lives (including troubles with other tribes), customs and faith are depicted with respect and admiration. We are introduced to their concept of a great circle of life, symbolized in part by the medicine wheel.

In His Teepee

Rather than allow viewers to meditate upon these cultural norms, though, the series sentimentalizes them. As the main white protagonist gushes at the end of the first episode when he has decided to live among the superior Lakota, "We have a wheel that takes you from here to there. They have a wheel that takes you to the stars."

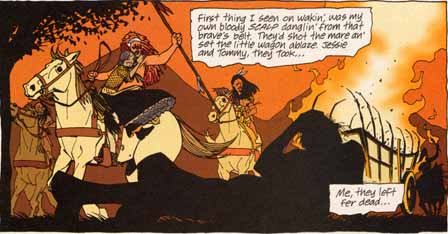

Apparently, however, there still is a limit to how much respect Indians can get on TV. They seem to be marrying whites all the time, as if the show's creators think this is the only way the audience will truly embrace and relate to them. Perhaps the most ludicrous seduction scene ever filmed appears in a segment typical of the series' new-cliché mode. A young white woman is abducted by Indians, lathered with love oil by an old woman and then brutishly pounced upon by Prairie Fire, a Cheyenne warrior whom she fends off by reciting "Miss Muffet" and other nursery rhymes (the Indians think these are evil-spirit incantations). But she grows to admire her suitor after he refuses to trade her to another Indian for a fancy pelt. Next thing we know, the hunky Prairie Fire is reclining by the fire in his tepee, as the now-kittenish abductee shakes her Ann-Margret tresses down her bare back and coos "Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star" to him.

Nancy DeWolf Smith, A West That Never Was, Wall Street Journal, 6/10/05

Overshadowing all of this, however, is Spielberg's influence on the series, and his directors' and scribes' definition of what balance and fair portrayal of Native Americans entails.

The "other" side of the story is the struggle to maintain the Lakota way, something never stated in concrete terms, but which we're meant to take as clinging to spirituality and arrows, limiting exposure to the white man's rifles and wagons. When they trade with whites, it usually leads to terrible things.

This brand of New Age, "Dances With Wolves" hooey is merely a different shirt on the "noble savage" stereotype. And there's enough of it present in "Into the West" to make a conscientious person squeamish. The writers and directors must have felt it as well, which is why the Lakota characters lack dimension, emotional range and receive less screen time in episodes two and three.

Melanie McFarland, 'Into the West' Manifests Itself as Shallow 'Roots', Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 6/10/05

Even more irritating is Into The West's PC approach to history. Spielberg idiotically tries to cast this as an American Schindler's List; white explorers and settlers rampage around the continent like unaccented Nazis (the gallant Wheeler family standing in for Oskar Schindler) while the Indians are their perpetually innocent victims. If the Indians massacre a wagon train, it's only to prevent the spread of disease; if the Indians abduct and rape a woman, she falls in love with them. Indian mysticism is portrayed as profoundly spiritual; white Christianity as fundamentalist fanaticism.

There was plenty to criticize in the way Old Hollywood did Westerns, portraying Indians as one-dimensional savages. But simply reversing the formula is not the answer: The mirror image of bigotry is still bigotry.

Glenn Garvin, An Epic Story Reduced to Tedium and Clichés, Miami Herald, 6/10/05

Dennis Zotigh, a Kiowa/Pueblo/Sioux man who is a historian for the Oklahoma Historical Society, says "Into the West" is hardly true to Indian people. "Historical inaccuracy, perpetuation of negative stereotypes and status quo mentality abound in this production," he says. "In the roughly 10-minutes of portraying interaction with the Mohave tribe, the Indians get drunk, the young women immediately offer themselves to the explorers and a quiet village of stoic Indians hang around camp with no dialogue to speak of. Several were wearing $5.00 Mexican blankets available from Stuckey's and Loves Country Stores."

Historian Pans Into The West, The Native American Times, 6/10/05

Rob's review

I finally saw Into the West late in 2005—the first couple of episodes, anyway. As usual, it was worse than the critics said. These people aren't attuned to Native stereotyping, but I am.

The following are some of the problems in the first episode:

The first Lakota we meet have stereotypical names—Soaring Eagle, Growling Bear—that telegraph their personalities and roles. Fortunately the names get less clichéd as the series goes on.

The first time we meet Thunder Heart Woman, the Lakota give her to a white trapper, Lebeck, to marry. They want to seal a political alliance with the Anglos, he finds her fetching, and she goes along with it. These actions belie Thunder Heart Woman's strong name. Despite her name, the Lakota (and the series) treat her like a second-class citizen—the proverbial "squaw." She's far from being a force equal to the male characters.

Which isn't to say all the women should be strong and independent. That wouldn't be realistic in a male-dominated world. But in Into the West, none of the women are strong and independent. Except in their (thunder) hearts, where they stoically endure hardship while standing by their men.

Thunder Heart Woman is young and beautiful by Hollywood standards. She could be a model. So are the next Indian women the trappers encounter: the Mojave. There are no women who are overweight or wrinkled or weathered—who look as if they've lived through hard times without Botox or plastic surgery.

To sum up the Indians so far: the Lakota are good and noble. They've done nothing but engage in spiritual practices: visions, healing, praying. All the other Indians shown or mentioned are immoral or criminal.

Indians serve their purpose

Whew! And that's only the first episode!

In this episode, Into the West conveys the impression that it'll feature the Indians and white men equally. By the second episode, you realize the Indians have already served their purpose. The audience has the idea: The good Indians are spiritual and mystical...immersed in their dreams and rituals...and doomed by their unwillingness or inability to change. The rest of the Indians are bad Indians, so they're irrelevant and deserve to disappear.

Once you understand what the Indians represent, there's little need to follow their story. They've shown us that Indians were noble savages. Now they can move off-stage while we follow the real story: how the West was won despite such politically correct perils as disease and disaster.

The second episode isn't as bad—but only because the Indians have a much less prominent role. Some problems in this episode:

Naomi grows to love her Cheyenne warrior, who naturally is a Fabio-style hunk and a really nice guy. But the tribe considers selling her to someone from another tribe—yet another example of treating women as chattel.

That's about as far as I got with Into the West. It's more than enough for me to conclude that the series was stereotypical.

More reviews

Roundup: Reviews of TNT Series 'Into the West'

After the production

Some of the Native Americans who worked on TNT's 12-hour miniseries "Into the West" allege they faced harsh working conditions, were frequently underpaid and that the production violated child labor laws.

James Hibberd, Unrest in the West, TV Week, 6/13/05

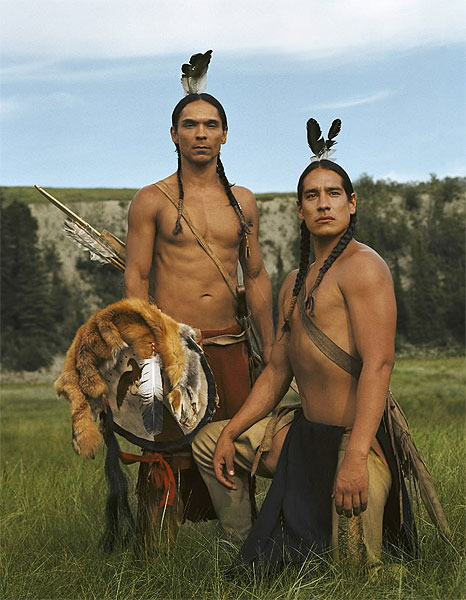

Irene Bedard, who plays Margaret Light Shines Wheeler, the daughter of a Lakota and a settler, confirms that weather on location was awful. "Snow and mud and wind... we were all cold," she says, adding that the low temperatures were harder on the Native American actors, who were wearing skimpier costumes, than on the white actors in settler garb.

Dispatches from Into the West, TV Guide, 7/8/05

More on Into the West

An Emmy for Spielberg?

Official website for Into the West

Related links

TV shows featuring Indians

The best Indian movies

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.