Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

For a critical overview of the 2006 movie End of the Spear, see Spear's Point Is Obvious. According to the critics, the movie is stereotypical as follows:

From Waging War and Peace in the Amazon Basin in the NY Times, 1/20/06:

[T]he humane message of the film (directed by Jim Hanon and written by Mr. Hanon, Bart Gavigan and Bill Ewing) is undercut by the religio-mythic trappings attached to it, and by an inescapable air of Kiplingesque smugness in its portrayal of civilized whites enlightening rampaging dark-skinned savages.

.

.

.

The sleek, mostly Latino actors portraying members of the violent Waodani tribe, who achieve peace and harmony with the surviving missionaries after murdering five, are only marginally more authentic than the American Indians played by Hollywood extras in 1950's westerns. Louie Leonardo, the Dominican actor who portrays the tribe's most violent warrior, Mincayani, suggests a less steroidal version of the Rock in his displays of acrobatics and spear-wielding virtuosity.

From Point All Too Obvious in Bluntly Didactic Jungle Adventure in the San Francisco Chronicle, 1/20/06:

[T]he natives are portrayed as ominously nasty from the get-go. Their nostrils practically flare. They're presented as broad caricatures, like the Indians in early Westerns.

From 'Spear' Misses Target in the Hollywood Reporter, 1/20/06:

In the end, some vibrant cinematography aside, "End of the Spear" bears an unfortunate resemblance to those old '40s jungle B-movies, a quality underscored by composer Ronald Owen's overwrought and decidedly un-PC soundtrack, which goes awfully heavy on the drumbeats and tribal chanting save for the times it echoes John Barry's lush "Out of Africa" themes a little to closely for comfort.

From 'End of the Spear' Shoots ... and Misses in Indian Country Today, 2/8/06:

Not everyone has bought into the pro-assimilation message of "End of the Spear," however. Its depiction of indigenous people as savage brutes parrots a familiar refrain: As an editorial in the Cornell (N.Y.) Daily Sun put it, "From the start, the Waodani's ways are portrayed as generally wrong and those of the missionaries are generally right ... Such a patronizing view is somewhat disturbing in its efforts to make the very grey territory of cultural interaction into a black and white portrayal."

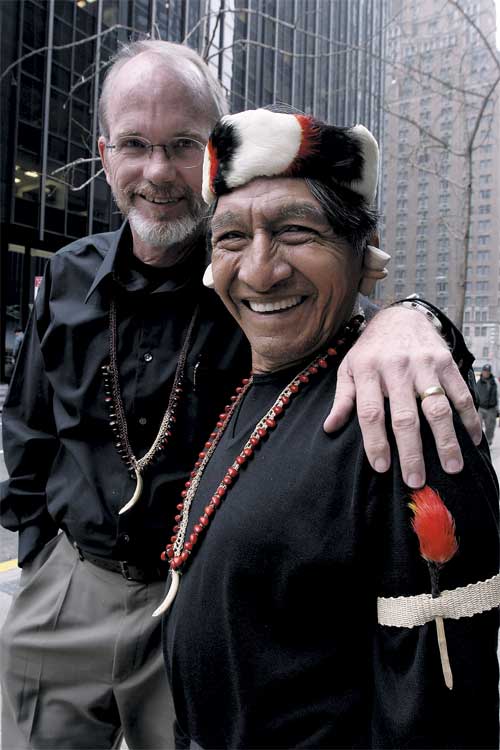

The film's viewpoint distracts viewers from contemplating the catastrophic effects such an intrusion has had on the Waodani's land itself, according to New York Daily News movie reviewer Jami Bernard: "In reality, the intrusion of Western ways has been disastrous to the region, where oil and logging concerns are stripping land and culture. In documentary footage played over the closing credits, the real warrior is introduced to American fast food and returns to his people too fat and sluggish to spear himself a snack, let alone a missionary."

"End of the Spear" avoids exploration of the negative effects of the Waodani's "Westernization," focusing instead on the pacifism missionary contact brought to a tribe described by anthropologists as the most violent people ever documented (their fierceness prompted Shell Oil Co. to abandon plans to perform exploratory drilling in 1948). The tribe's struggles to reorganize its internal power structure and represent itself to the outside world in the wake of Western influence also go unexamined.

What happened to the Indians?

Around that time one of the murdered missionary's sister, Rachel Saint, achieved what would become for the most part a peaceful contact with them for the rest of her life. (Saint's story is well documented; see links at the bottom of this page.)

A lot of her life was spent learning, and contributing to our linguistic understanding of, the Huaorani language. (As you can see above, their language to this day has defied classification by linguists.) Her informant in learning the language was a young Huaorani woman named Dayuma. Between them they began missionary work, reaching many of the Huaorani around Dayuma's home. They are still today more responsible than any other two people for missionizing the Huaorani.

In the late 1960s the oil company, Texaco, approached the Ecuadorian government hoping for permission to drill for oil on Huaorani land. Saint and Dayuma became a key part of the following massive displacement of hundreds of Huaorani. Before then most had remained on their ancestral lands, uncontacted, and living the same hunting/gathering lifestyle that hadn't changed in millennia. What is known about this lifestyle is that the Huaorani cultivated almost no crops or plants and relied on hunting for their meat and fish. They were experts in, and had a symbiotic relationship with, the rainforest. That relationship transcended into the spiritual. Shamanism was practiced, which included the use of naturally occurring hallucinogens. Animistic ritual and polygamy also characterized traditional Huaorani beliefs. They believed in a symbolic relationship between their environment and themselves. The forest would always provide enough that they didn't have to grow food or keep animals. Leaves were like their children. They believed strongly in their history of and desire for independence. In fact at the age when our children enter second grade, Huaorani children became to a large extent independent of their parents — hunting and gathering their own food!

The missionaries and the Ecuadorian government agreed to relocate as many Huaorani as possible away from the drilling areas to the missions that had been established in the previous ten years. Hundreds were relocated, while others fled to even more remote parts of the jungle. Accounts of the relocated Huaoranis' experiences differ. At one extreme, some have written of this event as "ethnocide." Others have claimed that it saved the Huaorani from genocide at the hands of the oil companies. An unquestionable outcome is that many had their life and culture changed forever, while others chose (and in some cases were never presented a choice) to stay deep in the forest and live the way they'd only ever known.

The visitor can see this polarization today in Ecuador. Eventually, many missionized Huaorani moved to so-called oil frontier towns, particularly Coca. Spanish is now their first language; drug abuse is high.

Waddington, R. The Huaorani. The Peoples of The World Foundation. Retrieved March 7, 2007, from The Peoples of The World Foundation.

More on End of the Spear

Rob's review: Spear gives viewers the shaft

Spear gets a goose-egg

Related links

Indiana Jones and the stereotypes of doom

Savage Indians

The best Indian movies

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.