Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

It Takes a Village

To stave off bankruptcy, a small town declares itself an Indian tribe and welcomes casino gambling.

Reviewed by Tom Perrotta

Sunday, November 19, 2006; BW07

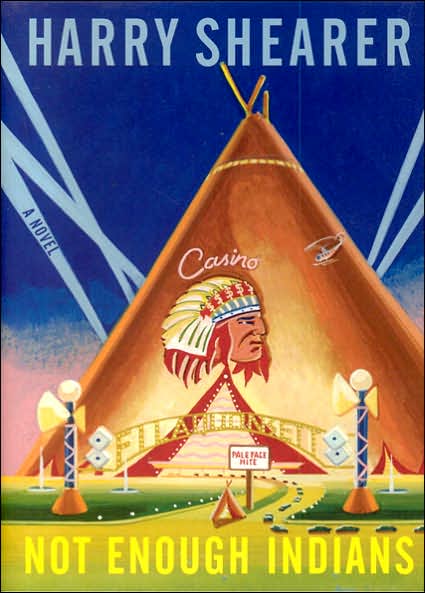

NOT ENOUGH INDIANS

A Novel

By Harry Shearer

Justin Charles. 225 pp. $19.95

Harry Shearer occupies a peculiar niche in our pop cultural landscape, somehow managing to be legendary (he played the cucumber-packing bassist in "This Is Spinal Tap"), ubiquitous (he supplies the voices of Ned Flanders and Mr. Burns, among others, on "The Simpsons") and more or less unknown to the general public. For a guy associated with so many high-profile undertakings (he was also a writer and cast member on "Saturday Night Live" in the early 1980s), Shearer probably doesn't get pestered too much for his autograph while shopping for groceries.

As any writer whose last name isn't Rowling or Grisham will attest, publishing a book doesn't usually pose a serious threat to one's status as a non-famous person, so it's safe to speculate that the arrival of Shearer's first novel — an engaging political satire called Not Enough Indians— probably won't turn him into a household name. But the book should serve as a welcome reminder of Shearer's extraordinary versatility as an artist and solidify his reputation as a keen-eyed comic observer of American life.

Not Enough Indians is a high-concept novel in the Christopher Buckley mode, with a premise that's at once utterly outrageous and weirdly plausible. The town of Gammage, N.Y., is in deep trouble: The factories have shut down, the roads and schools are in disrepair, and the beleaguered municipal government can barely afford to collect the garbage. Even the public radio station has closed, replaced by a "Christian radio network that features 'Hot Jesus Talk.' "

After failing to woo a Wal-Mart or sell "naming rights to a big ugly building on the wrong side of town," the city fathers find temporary economic salvation in the unlikely figure of Tony "Loose Slots" Silotta, a thuggish mogul from Las Vegas looking for a piece of the lucrative Indian casino action. Hoping to beat the dubious Wowosa tribe of Connecticut ("It's not wow! It's Wowosa!") at its own game, Silotta makes the town of Gammage an offer it can't refuse: "Let me get this straight," a pony-tailed selectperson says. "You want us to get the entire population of the town recognized as an Indian tribe so that we can open a gambling casino?"

The bureaucratic obstacles to this fraud turn out to be easier to navigate than one might expect, due to the fact that Vince Winstanley, a deputy assistant secretary at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, just happens to be under pressure from his boss to speed up the certification of "the unrecognized tribes, 250 groups of Native Americans who enjoyed neither tribal sovereignty nor the unalloyed pleasures of reservation life because the federal government had never signed treaties with them." Add a smooth-talking Washington lawyer to the mix and before long, the citizens of Gammage have been reborn as the Filaquonsett tribe, upon whose newly sovereign land Silotta constructs a "vast, galactic" casino, big enough that "two Wowosas and an Office Depot" can fit inside it.

Shearer is at his satiric best in chronicling the absurdities of Gammage's cultural and economic metamorphosis. Embracing their new identity with more fervor than seems absolutely necessary, many Filaquonsetts actually seem to believe they're Indians: "We prayed to Ngadala, the god of the sun and the moon, to rescue our tribe, and our valley, and our prayers have been answered," Dr. Gardner declares, while wearing a headdress and a three-piece suit. The townspeople learn the ceremonial Eagle Dance and greet each other with the words, "Hya, hya, hya." Needless to say, the Wowosas are not amused, and soon the two ersatz tribes are engaged in a very real battle for survival.

For a relatively short book, Not Enough Indians is packed with characters, a rogue's gallery of earnest city officials, long-winded local activists, unctuous consultants, wily bureaucrats, Native American hucksters, Vegas high-rollers and assorted eccentrics. This crowded field plays to one of Shearer's strengths as a writer: He's a master of the thumbnail sketch. But at times, entertaining and politically astute as it is, the novel seems to lack a center, a single character or relationship that the reader can track all the way from beginning to end.

Arriving on the heels of the Jack Abramoff scandal, Not Enough Indians may also suffer a bit in comparison to that epic tale of casino-related corruption. None of the characters in Shearer's novel seems as operatically venal as Abramoff or as nakedly hypocritical as Ralph Reed, the fallen choirboy of the Christian right. As Philip Roth pointed out way back in the '60s, American reality is always running a step or two ahead of the imagination of even our boldest novelists. ·

Tom Perrotta is the author, most recently, of "Little Children."

Shearer explains himself

Harry Shearer

The comedian and media expert on Indian gaming, the Jerry Lewis telethon, and why New Orleans isn't funny

CityBeat: Was the town of Gammage modeled on any particular town? Do I see the Santa Monica City Council in there?

Harry Shearer: It partakes of two or three towns that I know pretty well, none of them in New York state. People can hear echoes of whatever they want. But I certainly have been a fan of the Santa Monica City Council radio show for a long time. Despite my wife's earnest entreaties to "Turn that thing off!"

Did you research the casinos and their culture for this book?

Yeah. I talked to people knowledgeable on both sides of the issue, including a lawyer in Louisiana who is the leading anti-Indian-gaming attorney in the country, apparently, C.B. Forgotston – unforgettable name and a remarkable guy – and I got connected to a resource that's operated by one of the members of the Pechanga tribe that sort of aggregates an awful lot of information about Indian gaming – I'm sorry, gambling! Who are we kidding? The Vegas stuff had come to me earlier when I was working on a [1986] television show I did with Paul Shaffer for HBO called Viva Shaf Vegas.

The town of Gammage votes itself to become the Filaquonsett tribe. That's probably been going on all over the country.

As I tour the country, I hear the most amazing stories about, "Gee, that's sorta like what's happened here." My inspiration was the Mashantucket Pequot, which was the tribe that opened the first really big Native American casino, Foxwoods. When they opened, The New York Times ran a piece saying that the number of full-blooded Mashantucket Pequots living on tribal land at that point was one. So, I just went: "One take away one is a funny idea for a book."

Has there been any reaction from Native Americans about your book?

Unfortunately, no! I don't know necessarily what they'd be ticked off about, but I wish they'd be ticked off about something, 'cause it helps book sales.

What about the whole idea that a tribe can create itself out of the dust?

Yeah! Well, on the other hand, the story is – in some lights – a revenge fantasy. Because Jennifer New Moon is sorta the voice of the traditional Native American [who] just refuses to be pigeonholed into either buying or not buying whatever the white man is selling.

Are the casinos themselves the ultimate revenge fantasy? Are the tribes getting rich at last?

That's the thing I was trying to figure out. It reminded me very much of when I did a very long piece of journalism about the Jerry Lewis telethon, and I tried to get the answer to the question: Does Jerry get rich off this? And everybody you talk to had a slightly different answer. The same with this. Forgotston maintains that not one single, actual, working or nonworking Native American has benefited from Native American gambling. But there are plenty of other people who disagree, who say there are tribes who built schools and hospitals. So I think it depends on how corrupt or not the leaders of any particular tribe are at any particular time.

Rob's comment

The premise of Not Enough Indians is stereotypical. It couldn't come close to happening in reality. Among the problems:

Not Enough Indians is obviously a takeoff on the Mashantucket Pequot situation. For a critique of the critics who say the Pequots aren't Indians, see The Critics of Indian Gaming—and Why They're Wrong.

Even if the critics were right, this would be an extreme case. Portraying extreme cases as the norm—as everyone from Time magazine to the SCALPED comic book has done—is stereotypical.

And yes, I realize Not Enough Indians is supposed to be satirical. It's a satire based on a stereotypical premise: that the US government is recognizing any group that declares itself to be a tribe.

Incidentally, Shearer speculates that not a single Indian has benefited from gaming?! That's ironic considering he refers to PECHANGA.net, the Internet news source. The owner of that website has almost literally gone from rags to riches because his tribe runs a casino.

That Shearer would even present this as a "he said/she said" kind of controversy shows his bias. There's no controversy about whether Indians have benefited from gaming except among ignoramuses and illiterates. They clearly have.

Others agree

Funniest part is the impossible premise, January 26, 2007

Reviewer: LaLoren "laloren" — See all my reviews

Let's start by saying that I think Harry Shearer is a funny guy, and I don't mind "stereotypes" that include some truth. For example, I found Tony "Loose Slots" Silotta pretty funny, even though I'm Italian-American. But as one of the handful of non-Indians, outside of those working in Indian law or the BIA, with enough knowledge of the real issues to review this book, and given that any American Indian reviewing it would probably be seen as prejudiced, I've got to say that the most knee-slappingly hilarious aspect of this book is the premise that federal recognition could ever be that easy or that the Senate Committee (it is not a subcommittee) on Indian Affairs would or could suddenly push BIA to recognize any Indian nation with so little research, or that a tribe with a majority of members claiming 1/32 Indian blood could ever qualify.

I have to admit, I've never understood why so many people find American Indian gaming such an inherently funny idea (my reading of this book happened to coincide with the viewing of an old Family Guy episode with the same theme) while state-run or state-sanctioned corporate gaming that promises, but rarely delivers, even half the benefits that Indian gaming provides for both their own and surrounding communities isn't seen as an even bigger hoot. Sadly,Shearer buys into all the common—and generally mistaken—notions the average person holds re: Indian Gaming: that just about anyone can call themselves a "tribe" thus gaining federal recognition and a smooth sail into lucrative casinos, and that Indian gaming provides a safe haven for organized crime.

If I recall, recent BIA statistics show that recognition takes an average of 7 years. However, it isn't unusual for it to take as long as twenty given the arcane rules and paperwork involved. Indeed, the time and expense is often more than small nations can afford. Second, Indian gaming is the most highly regulated in the country, and while many a reporter has hoped for that big lead, they can find no links to organized crime.

The saddest part about this book is that Shearer appears to have some knowledge of American Indian issues. Unfortunately, he could have used his knowledge in a better way. No, I do not believe that all novels about Indians have to be like "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee." In fact, literature by Native Americans is often extremely humorous. With the research he obviously did into the workings of the BIA, the story of a Indian nation trying to wend their way through that maze could have been really funny. Or how about a guy like Tony Silotta trying to get into the Indian Casino business and finding himself, for the first time, hitting a brick wall (there was very humorous Sopranos episode along those lines), or how about a state government trying to balance its budget by fleecing Indian casinos—or maybe that's too true to be funny.

Sad that someone with such a creative sense of humor ended up settling on a cliche that, unlike most cliches, isn't even based in truth.

Jennifer Brown says:

The plight of unrecognized tribes in the US is not really something to be made fun of. There are literally hundreds of tribes that cannot attain federal recognition and their members suffer the discrimination that comes from being Indian without a legal status. I realize this book is a satire, but wow, what a poorly chosen subject.

While casinos might seem ripe for satire, the income made from the very small number of tribes that have casinos is miniscule in all but a very few tribes. The perception of widespread wealth from casinos stands in stark contrast to the widespread poverty on most reservations. To perpetuate this misconception does damage to tribes striving to do the best for each member.

Shonna Gariepy says:

Ever think that it's often satire that brings the sadness of the plight of the Native Americans to the front and center? If it's comedy that opens peoples' eyes to the plight of tribes and discrimination, then let comedy be the light!

I do not believe that casinos are the answer for the Tribes, but so many of them have latched on to the casino for the gambling and the booze and everything else they entail — it's a sad state of affairs. If Harry Shearer can show through satire just how sad the casino world is — and it is, then so be it. Tell the tale and let's see if some small truth has shone through that *Satire* — that greed and booze and gambling etc is not the answer. You might not agree with his reasons for writing this, however could it be that his reasons for writing this book include a satirical look at the indian casinos, those looking to manipulate the system and take advantage and *gasp* perpetuate the misconception?! BTW, have you read his book?

LaLoren says:

I have read the book and you can read my review.

By what measure is Indian gaming a sad state of affairs? I live in Pennsylvania—yet another state that has just turned to gaming as a panacea for all our property tax woes. Even though, right next door in NJ, property taxes are some of the highest in the nation 30 years after Atlantic City was turned over to corporate gaming operations. That is the sad story. Not Indian gaming that, in contrast, has brought much needed money, not only to projects that benefit the Indian communities that run them, but surrounding communities as well. The statistics are there if anyone cares to read them. In fact, post-9/11 Gov. Pataki looked toward compacts with Indian casinos to solve New York's economic problems.

The problem with Shearer's book is that so much is just inaccurate. As the earlier poster notes, federal recognition is extremely difficult to attain even for Indian nations who were here to greet the first settlers. They have to prove a continuous existence—not easy when their decimation and then termination was the government's goal. There is simply no way that those two "tribes" would ever have gained recognition.

Unlike state-sanctioned corporate gaming, NAGRA specifies that profits from Indian gaming must go toward tribal needs. Your reference to "booze" is an interesting one because much of gaming procedes has gone toward substance abuse programs, education, community centers for youth, diabetes education, just to name a few. In a handful of nations with truly lucrative casinos a per capita income is also paid to members. I'm not sure why the idea of wealthy Indians is so repulsive to Americans as opposed to corporate casinos where profits go to shareholders and the state only hopes they pay enough in taxes to make the whole thing worthwhile.

I could go on and on, but I'll end by saying that I strongly disagree with your ideas of why this book may have been written. Satire only really works when it is based on truth. I'm Italian-American and I'm not complaining about Tony Silotta. Sure he's stereotypical, but there's a lot of reality in his character as well. Unfortunately, though, the premise of this novel is based on what the public wants to believe or a fake impression created by the media. Satire based on that really isn't satire. It's a perpetuation of misinformation.

Related links

Indian wannabes and imitators

The facts about Indian gaming

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.