Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Native American groups demand apology for shirts

By Daisy Chung

Wednesday, January 25, 2006

last updated January 25, 2006 12:54 AM

For many students, the Stanford Cardinal has always represented the University on its playing fields, exemplifying the spirit of the school within its ranks and to the community at large. However, alumni who attended Stanford before 1972 might recall an entirely different mascot — the Stanford Indian.

With an increased sensitivity to the issues at stake in a multi-cultural community, the University officially replaced the Indian mascot after 55 students and staff members submitted a petition asking that the symbol be removed.

In recent months, however, the Native American community at Stanford has noted a reemergence of the Stanford Indian on various spirit and athletic paraphernalia.

"We were extremely disappointed by the recent reappearances of the Stanford Indian," said senior Jackson Brossy, co-chair of the Stanford American Indian Organization (SAIO).

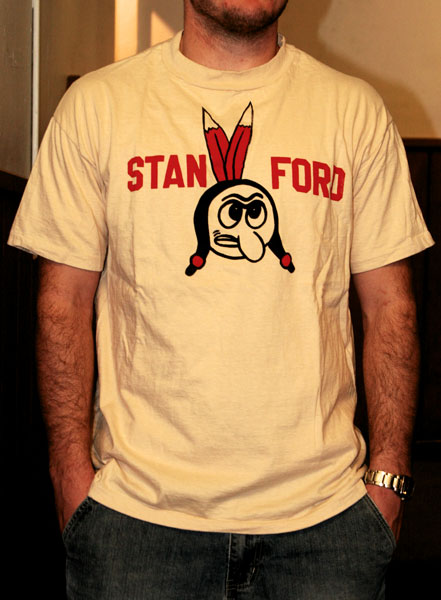

One incident involved T-shirts advertised in the varsity sailing team's newsletter. Members of the sailing team and head coach Jay Kehoe declined to comment.

"The T-shirts were printed by an alumnus before Big Game — the individual intended to distribute them to other alums and members of the sailing team," said Gary Migdol, assistant athletic director.

He explained that the T-shirts featured an Indian sitting on a bear.

"I believe there were 25 T-shirts printed, and five were left over after Big Game," he said. "The alumnus suggested that the team sell these shirts, and an ad was placed in the sailing team's newsletter."

Members of the Native American community at Stanford noticed the shirts and brought the issue up for consideration within their organization.

"The sailing team plans to print a letter in their next newsletter apologizing for the advertisement, which was inappropriate," Migdol said.

In another sighting of the Stanford Indian, the Sigma Chi Fraternity designed Big Game shirts that used the "Chief" logo this past November.

"There has been a recent resurgence of the Stanford 'Chief' logo throughout the campus and our use of it was meant to invoke visions of tradition and history (which was reinforced by the phrase 'Killing Bears since 1892...' on the back of the T-shirt), not racism or intolerance," said senior Kunal Gullapalli, president of the Alpha Omega Chapter of Sigma Chi.

Representatives of the Native American community, however, took offense at these images.

"These symbols, caricatures, and crude sketches of American Indians are to the Stanford community, especially the Native American community," Brossy added. "Characterizing more than 500 individual nations as wild-eyed, big-nosed, tomahawk-chopping savages is racist and cannot be tolerated by the greater Stanford community."

Student groups who have resurrected the Indian maintain that they were merely referencing the University's history.

"There was absolutely no intention of offending any group with this shirt (with the possible exception of the UC-Berkeley Bears)," Gullapalli wrote in an e-mail to The Daily. "We still recognize that, while our good intentions may be clear, any use of images representing racial stereotypes can negatively impact the consciousness of our community. Thus, Sigma Chi looks forward to proactively cooperating with the University and campus groups to resolve this unfortunate misunderstanding as well as working towards preserving our open and respectful campus,"

Members of the Native American community on campus are also working toward a renewed awareness of the issue within the larger Stanford population.

"We plan to deliver a letter to President Hennessy, the athletic director and the University [today], asking for a public denouncement of the use of the mascot, and a reiteration of the message that the use of the American Indian mascot will not be tolerated because it is demeaning and offensive," Brossy said.

By James Hohmann

Monday, January 30, 2006

last updated January 30, 2006 1:21 AM

Under pressure from Native American student groups, University President John Hennessy condemned the recent reemergence of the Stanford Indian logo on campus in a statement released Thursday.

"I am disappointed by recent incidents in which some Stanford students, staff and alumni have condoned the use of the Indian caricature in connection with University activities," Hennessy wrote. "This image is one that no member of our community should support, and I appreciate that it is particularly hurtful to Native American students, staff and alumni."

The statement seemed to come in part as a response to a letter delivered last Wednesday to Hennessy by the Stanford American Indian Organization (SAIO), as well as increased attention from local media outlets.

The letter, signed by SAIO Co-chairs senior Jackson Brossy and junior Jenny Patten, listed three instances of the symbol being used and insisted that Hennessy "help discourage future use of these Stanford Indian images and terms."

"The Stanford Native American Community is outraged, and SAIO — with support from AASA, BSU, MECha and MSAN — request your office officially rebuke the misuse of the Stanford Indian," they wrote.

Hennessy implored University stakeholders to respect Native Americans, invoking the Fundamental Standard in his press release.

"I urge all members of the Stanford community to comply with our policy that use of the symbol be discontinued," he said. "Moreover, I ask that we all take seriously the commitment in the Fundamental Standard to treat all members of the community with respect. Such respect is central to our existence as an academic community, and each of us has a responsibility to uphold this commitment."

The letter's authors told The Daily that they were pleased with Hennessy's statement, adding, however, that they hope more is done.

"The Stanford American Indian Organization is very pleased with both responses by Hennessy and Dean Boardman," Patten and Brossy wrote in an e-mail to The Daily. "We appreciated their timely reaction to our concerns and will continue to hold them accountable for upholding the policy when future mascot incidents occur. Despite this tremendous step forward, we still hope to arrange a meeting with Hennessy to recommend a more stringent policy for reacting to the wearing, printing, selling or promotion of the Stanford Indian mascot by Stanford affiliated parties."

One of the groups that was recently drawn criticism for its use of the Indian on Big Game T-shirts responded favorably to the president's statement.

"Sigma Chi fully supports the statement released by President Hennessy regarding the use of the Indian caricature," said Sigma Chi President Kunal V. Gullapalli, a senior, in an e-mail to The Daily. "Our chapter plans on meeting with University officials and student groups to resolve this issue and address any remaining concerns."

The Indian symbol, which had been the official Stanford mascot, was rejected by former University President Richard Lyman in 1972 at the insistence of Native American groups and some alumni. Since then, the same Native American groups have been watchful of any use of what they hold to be an offensive symbol.

In preparation for Big Game, the Sigma Chi fraternity prepared shirts featuring the Indian killing a bear, the symbol of Stanford's arch-rival, U.C. Berkeley.

In a separate instance, an alumnus of the sailing team printed T-shirts invoking the logo. An advertisement was later placed in the sailing team's newsletter to sell five left-over shirts.

Both parties backed down when Native American groups voiced concerns. Sigma Chi said they had not intended to offend Native Americans. Instead, they said they felt the Indian highlighted memories of tradition and history.

An Athletics Department spokesman said that the sailing team will print a letter of apology in their next newsletter.

"I fully support President Hennessy's comments," Sailing team head coach Jay Kehoe told The Daily. "We were in complete error in printing that shirt and using it for anything. It was an alumni-based shirt and our alumni have been written a letter to and asked not to use it."

The University administration's swift condemnation of groups using the Indian logo stands in stark contrast to some other universities around the country where administrators are joining prominent alumni and students to actively fight an August NCAA decree that they remove Indian imagery and mascots. In some cases, as with the Seminole Tribe of Florida, Native American groups have vocally supported the use of the Indian as a mascot, arguing that it represents courage, fierceness and other positive characteristics — not hostility or racism.

Presidents at both the University of North Dakota and Florida State University have been vocal supporters of their use of Indian symbols.

"That the NCAA would now label our close bond with the Seminole Tribe of Florida as culturally 'hostile and abusive' is both outrageous and insulting," said Florida State President T.K. Wetherell in an August statement on his school's Web site.

"Our logo was designed by a very well-respected American-Indian artist," said North Dakota President Charles Kupchella in an open letter sent to the NCAA and posted online. "The logo is not unlike those found on United States coins and North Dakota highway patrol cars and highway signs. So we can't imagine that the use of this image is abusive or hostile in any sense of these words."

"Long live Lightfoot?" Are you serious?

By Adam Bad Wound

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

last updated February 22, 2006 3:06 AM

Two weeks ago ("My name is Bad Wound: Listen to me on this one" Feb. 8), I wrote a column about the use of American Indian mascots in collegiate athletics, specifically addressing the situation at Stanford. In the column, I argued that the reaction of some students — as seen through letters written to the editor of The Daily — were a bit off mark. I argued that placing the debate in the realm of freedom of speech and tradition neglects to identify the ways that it intersects with the lived experiences of American Indian students at Stanford and elsewhere. Furthermore, I praised President Hennessey and the University Administration for evoking the Fundamental Standard and centering the issue as one of tolerance, respect and dignity.

This past week, the conservative student newspaper, The Stanford Review, published an op-ed piece by Executive Editor Milton Solorzano, a junior, titled, "Long Live Lightfoot!" (Feb. 17), in which he places the debate, again, back into the realm of tradition and legacy. In doing so, he evokes the story of Timm "Prince Lightfoot" Williams — the former mascot who was banned from performances by the University Administration in 1972 following a protest by the Stanford American Indian Organization (SAIO).

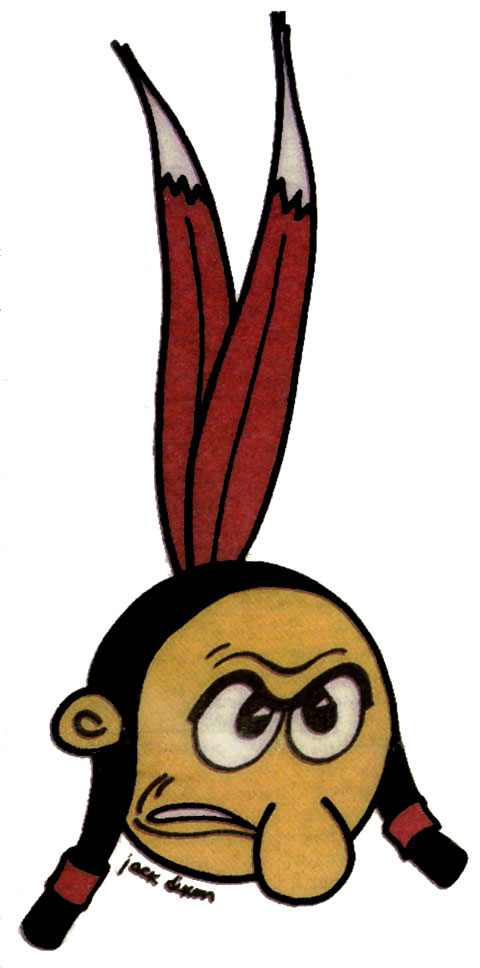

In my opinion, by mentioning Timm Williams and the "Prince Lightfoot" story, Solorzano pulls a fast one over our heads: he suggests that "Prince Lightfoot" and the current images of the "Stanford Indian" are one in the same, when in fact they are not. The cartoon character with feathers, braided hair and a "bulbous nose" as seen recently on t-shirts and through alumni efforts, makes no mention of "Lightfoot" next to the derogatory image. It is understood that the mascot was the "Stanford Indian." William's portrayal of "Lightfoot" was merely one interpretation of the mascot; it alone was not the mascot. Thankfully, the administration got rid of both.

In a weak effort to push the mascot debate into the realm of tradition and history, Solorzano argues that "like much of history, the reality of our past can't fit neatly within modern labels rubber-stamped by PC-obsessed university administration." First off, by focusing on the traditions of collegiate athletics, this line of argument neglects American Indian traditions entirely, much less the appropriateness of these traditions for mascot use. Secondly, I don't feel that the University Administration is being "PC-obsessed" in its confronting the image or evoking the Fundamental Standard. As stated in my previous column, I believe that the University Administration is centering the debate into the realm of tolerance and, very appropriately, reminding our community of the Fundamental Standard to which we are held.

In addition, Solorzano cites a Sport Illustrated poll in which the majority of American Indian respondents were not offended by the use of American Indians as mascots. Interestingly, Solorzano neglects to mention that Sports Illustrated is a division of AOL Time Warner, of which Atlanta Braves owner Ted Turner is the founder. In addition, the Sports Illustrated article about the issue makes minimal reference to the poll and does not include its sampling size or margin or error.

Somehow, Solorzano infers, "Thus SAIO's virulent, knee-jerk reaction, arguably, isn't even representative of most Native Americans." To clarify, the Sports Illustrated poll did not ask respondents about the Stanford case specifically, nor should it be interpreted to represent the American Indian community at Stanford.

I am hardly convinced by this evidence that the majority of American Indians do not object to the use of American Indian mascots, much less support it. And even if I don't have a majority to back me, I still think the use of American Indian mascots is disgusting, isolating and racist — and I think it should be no part of my graduate education at Stanford.

Solorzano concludes his op-ed article by suggesting that we "do nothing" to resolve the debate. He rightfully suggests that the mascot is not coming back, for better or for worse, but incorrectly argues that we should "let the memories live" and encourages us to "remember the positive aspect of our dated traditions." For the life of me, I can't understand what positive outcome the mascot issue has, a problem that is made no clearer by his op-ed article.

At this point, I have two recommendations. The first is that intelligent Stanford students stop reading The Stanford Review (if they ever did in the first place), and secondly, that The Stanford Review stops printing everything double-spaced. I'm no math major, but if the publication was single spaced, wouldn't that create half as much trash?

Anatomy of a Revolution: A brief history of the Stanford Indian

by Luukas Ilves

Features Editor

Why is everyone so angry today?

The current controversy over the Stanford Indian began at the most recent Big Game (and no, it didn't have anything to do with losing one more time). A number of people wore T-shirts with a bulbous-nosed caricature of the Stanford Indian that served as this schools mascot from the 1930s through the 70s. Several groups, including an alumni association with ties to the Sailing team, and the Sigma Chi fraternity, had printed these shirts.

On January 25 of this year, the Stanford American Indian Association (SAIO) delivered a letter to President Hennessy asking him to condemn the use of this mascot. Jackson Brossy, the President of SAIO, stated, "These symbols, caricatures, and crude sketches of American Indians are offensive to the Stanford community, especially the Native American community... Characterizing more than 500 individual nations as wild-eyed, big-nosed, tomahawk-chopping savages is racist and cannot be tolerated by the greater Stanford community" (Daily, 1/25/06).

Hennessy swiftly complied: "I ask that we all take seriously the commitment in the Fundamental Standard to treat all members of the community with respect. Such respect is central to our existence as an academic community, and each of us has a responsibility to uphold this commitment." These comments sparked a flurry of letters to the editor of the Daily on both sides of the issue. The situation elicited comparisons to the Danish mascot controversy, and comparisons of Hennessy to Western European elites who caved to anti-free-speech pressure. Others, like Sarah Trujillo, defended his comments, writing that the "problem with images of Indians as mascots or in the media is largely due to the fact that those images provide for other people an understanding of how an Indian 'should' look and behave" (2/3/2006).

The conflict did not, however, descend to its current lows until it evolved into a flame war between Daily columnist Adam Bad Wound and various members of the Stanford Review. Bad Wound wrote a response attacking an article about Stanford's former mascot in the Review by executive editor Milton Solorzano (see "Prince Lightfoot" below). Solorzano responded in a letter in which he attacked SAIO's tactics: "The Stanford American Indian Organization's knee-jerk reaction is a claim to ownership of history and a denial of certain traditions that they deem 'intolerant.' They should be congratulated on their efforts thus far — I'm willing to bet that less than one percent of Stanford's current population even knows who Timm 'Prince Lightfoot' Williams is." He concluded, "Somehow, I'm not surprised that members of the SAIO would consider their close-mindedness a compelling argument for restraint."

Bad Wound took this as a direct challenge, responding with a column titled "The Stanford Review: Oh, it's on!" (3/1/06). He called the Review insensitive to American Indian readers and "encouraged intelligent Stanford students to not read the Review." The Review's Emeritus Editor in Chief criticized Bad Wound's illiberal effort to stifle debate (3/2) and Bad Wound responded by calling the Review "racist" (3/8). This article will not take sides on the issue, but will instead survey the turns the conflict has taken in Stanford's past and how it relates to the current brouhaha. It will hopefully provide a background that will allow all involved to make more informed and rational comments.

1970 — The Beginning of Change

Our current mascot imbroglio harkens back to the early 1970s, when the administration eliminated the "Stanford Indian" as our official mascot. Many of the questions that still vex us first rose to the surface then, and many of the arguments on both sides of the debate find antecedents in the 70s.

The Indian had not always been Stanford's mascot. The Executive Committee of the ASSU adopted it around Big Game in 1930. For the next forty years, Stanford would enroll only a few Native American students. Their enrollment jumped in 1970, however, to twenty-six students when twenty-two Native Americans joined the freshman class. In November of 1970, a group of these Native American students petitioned the Acting Dean of Students, complaining that Stanford's mascot, Timm Williams, or Prince Lightfoot, did not represent American Indian tradition or culture in his performances at football games. The administration dropped the caricature of a large-nosed Indian, though the Indian did remain Stanford's official mascot.

1972 — The Floodgates Open

The issue returned in 1972 when a group of 55 Native American students submitted a petition to University Ombudsman Lois Amsterdam. The petition explained that it was "made necessary by the fact that that the non-Indian members of the Stanford community are not sensitive to the 'humaness' [sic] of their Native American counterparts." The petition objected to both the name Indian and the use of the Indian as a symbol. The petition read: "Stanford has placed the name of a race on its entertainment: A race is not entertainment. While the name remains unchanged, the ignorance of non-Indians likewise remains the same... People will fail to understand the human side of being Indian as long as they can choose instead to see only the entertaining aspects of Indian life." The petition also objected that performances by "Prince" Tom Williams "Lightfoot" and the Stanford Dollies were "degrading to the Indian population of the Stanford Community." In abandoning the Indian, the petition urged the University to "show a readily progressive concern for the American Indians of the United States" ("Improve Native American Programs," Stanford Daily, 2/7/72).

In her acceptance of the petition, Ombudsman Amsterdam commented that she "cannot add to the obvious force of the petition's statement of the demeaning exploitation of a race of people as a symbol of sports and entertainment." She apologized for the Indian's past use, explaining, "We did not intend to do so with malice, or with intent to defile a racial group. Rather, it was a reflection of our society's retarded understanding, dulled perception and clouded vision." Amsterdam expressed her hope that "the Alumni will be proud when the University removes any vestige of a symbolic use which degrades and insults members of our community." Amsterdam felt that the choice to eliminate the Indian was a self-evident one that called for no debate. "Because of the intensity of feeling of our Native American Community with regard to the Indian symbol... I do not recommend the kind of committee consideration which might be appropriate for a more complex matter."

Amsterdam's hopes for a quick resolution went unfulfilled. Her decision generated a torrent of letters and comments from students and alumni, including Native Americans, supporting the mascot and a corresponding torrent of responses from those opposing it. One of the first comments came from L.R. Garner ('50), a Navajo alumnus. He felt that the "Stanford community should take care not to be misled by the hasty advice of a small group of Indian students who clearly do not represent mature Indian opinion" (Daily Letter to the Editor, 2/8/72). His sentiment was soon echoed by other Native American alumni, including Robert Ames ('51), a Hopi Indian: "I am proud that he had the opportunity and good fortune to attend and graduate from Stanford; I am doubly proud that Stanford chose the Indian as its symbol and that the University and its students have in the past years displayed the intelligence, courage and with which I believe the symbol represents" (2/9/72).

These alumni found support from some students and community members outside of Stanford. Many commented on the parallel between the Stanford Indians and the Minnesota Vikings or the Notre Dame Fighting Irish. Other suggested that because the Indian embodied positive virtues it ought to stay on as Stanford's mascot. A number of people wrote in to suggest that focusing on the Indian as a controversy was a way to "expiate our forefathers' sins against this noble race" (Mildred Nilsson, 2/16/72).

These dissenting voices did not go unchallenged. Many students and professors wrote in support of abolishing the mascot. The Anthropology department sent a letter signed by 22 students and 15 faculty explaining, "It is the tenet of Anthropologists that each culture—and each Native American tribe—should be appreciated on its own terms and respected for what it is. Stanford's use of 'Indian' images makes a mockery of the proud peoples of this continent" (2/9/72). The Chicanos in the School of Education Association wrote in voicing their solidarity with Native Americans and protesting, "That the fun and games of college students should be meaningful to the most disfranchised group of people in this country just doesn't follow" (3/31/72). David Thompson, the Resident Fellow in Loro, the erstwhile Native American theme house, found offensive the "paternalistically racist argument that we Anglos are really using the Indian's name in a way that is good for them and will bring honor to them and why don't they understand our good intentions? I hope that most of us have lost enough of our racial naïveté to recognize this elitist view for what it is" (2/11/72). Chris Hocker, another alumnus, provided perhaps the most levelheaded commentary:

"People tend to forget that the full name of Stanford athletics teams has been the Stanford Indians, not merely 'the Indians.' This is not just a picky semantic point; rather, to use the term 'Stanford Indians' is to use the ethnic label of all Indians... who are at Stanford. These Native Americans have requested, unanimously, that their name not be used. Dropping the Indians as mascot is no matter of emotion, it is a matter of right."

Hocker went on to point out that Native Americans from outside the Stanford community who supported the Indian, "are not properly Stanford Indians" (3/28/72).

Who Decides

One of the questions that seem to accompany every public conflagration at Stanford is the question of who decides?—does the administration act unilaterally or give power to the student body?; Does the student body act through plebiscite or elected body? And the list goes on...

The initial decision to eliminate the Indian in 1972 was made by the University ombudsman. The issue was then handed to the ASSU Senate. The ASSU President Doug McHenry suggested to the Senate to eliminate the mascot and then allow the student body to vote on a new mascot. He was reluctant to allow the student body a vote on the mascot itself: "The Students are ignorant of what institutional racism is all about. This could be a problem of a democratic system squashing the rights of a minority" (Daily, 2/11/72). Confusion ensued over the next few months. The ASSU Senate voted 18-4 to abolish the mascot. President Lyman wished to submit the decision to review by a Senate committee established to review the issue. This committee included representatives from the student body, alumni, the Stanford Buck Club (antecedent to the Buck Cardinal club), the Athletics department, the Native American Students Association and the ASSU Senate. Doug Stone, a spokesman from the President's office, commented that he does not want alumni to feel that "the University is caving in to a pressure group or angry mob " (Daily 3/28/72).

The Committee sided with the Senate and the President and ruled against the mascot. This decision lead to some discontent in the student body. A group of students drew up a petition demanding a referendum with over six hundred signatures, more than enough to force a plebiscite on the mascot in the April ASSU elections. ASSU President McHenry refused to accept the signatures and the referendum went un-held. When the new ASSU President held a referendum on May 10, 58% voted against eliminating the mascot. President Lyman ignored the results.

Today, the Native American Cultural Center's website lauds that "The University decided in 1972 that any and all Stanford University use of the Indian Symbol should be immediately disavowed and permanently stopped,' and every year since then, the administration has reaffirmed its commitment by saying, simply, the mascot issue is not up for a vote!"

The question of a vote again came to the fore in 1975 when the student body was to vote on a new mascot. The students faced a vote on a number of different options, including Cardinals, Sequoias, and Robber Barons (but not Indians). "Robber Barons" received the largest number of votes, but was nonetheless not made an official mascot. Today, we have no official mascot, although the color cardinal serves as a nickname and is the primary color of the athletic teams.

Prince Lightfoot

The current battle has hardly avoided descending into arcane details. A tiff developed between Daily Columnist Adam Bad Wound and Review Executive Editor Milton Solorzano over the story of Timm Williams, who for twenty years performed as "Prince Lightfoot" at Stanford athletic events. Solorzano published an article in the Review ("Long Live Lightfoot!," 2/17/06) praising Williams for his long dedication to Stanford Athletics and enjoining us to remember the positive aspects of his legacy while also recognizing that the Indian was never coming back as Stanford's mascot. Bad Wound responded in the Daily ("Long live Lightfoot? Are you serious?," 2/22/06), lambasting Solorzano for "trying to pull a fast one over our heads" by confusing Williams, who presented but one interpretation of the mascot, with the mascot at large (Bad Wound does not address Solorzano's substantive claims about Williams).

Timm Williams has been causing a stir for thirty years. That he be barred from further performances at Stanford athletics events was one of the central demands of the petition Ombudsman Armstrong received in 1972. Professor Thompson called "The most obvious affront to the Native American community Prince Lightfoot's performance of a religious ritual which is, to the Native Americans and their elders a sacred rite and no more appropriate for the entertainment of a sports crowd than would be High Mass to a Roman Catholic" (2/11/72). Campus Native Americans saw Lightfoot's performance, which was usually done in the company of five Stanford Dollies dressed in stereotyped Indian clothing, as a desecration of their rights and culture. David Kennedy, Stanford's President in the 80s, wrote about the Indian issue in his memoirs. He recounts these comments from a distressed student: "You see something dignified and vaguely authentic. I see a Yurok Indian performing Plains dances in Navajo dress, and I find it troubling."

Timm Williams took issue with this characterization. He responded to accusations of the imprecision of his performance: "that's their interpretation. When I do them I feel they're authentic and I'm a real Indian." Williams told the Daily that "he has done his dance in costume at pow-wows of the Montana and Sioux and that these tribes have thoroughly enjoyed them." He added that "In my 20 years as Prince Lightfoot I've never been criticized for degrading Indians" (Daily 2/9/72). The historical record is quite clear that outside of his role as Lightfoot he was engaged in quite the opposite—championing the Indian cause. Williams served as elected leader of the 3000—strong Klamath River Yurok tribe, Chairman of the California Rural Indian Health Board, and director of the California Indian Assistance Project. He helped found the National Indian Health Board. To call him a fervent advocate for Native American causes does not seem a subjective statement.

Timm Williams's tribe, the Yurok, was perhaps among the most fervent supporters of the Indian. In late February of '72, they submitted a petition to President Lyman with the signatures of 107 Klamath-River Yurok urging him to reconsider Stanford's dropping of the Indian. According to the petition, "The overwhelming majority of our American Indians are proud of our traditional identification with Stanford University and the cherished historical symbolism of the 'Stanford Indian'." Attached to the petition was a letter from Dorothy Haberman, Secretary-Treasurer for the Tribe. She had harsh words for Stanford's Indians: "If the students were insulted or incensed by the word 'Indian,' the solution could perhaps be handled by changing schools rather than changing the symbol." After commenting that she found opposing the Stanford Indian "a selfish act" by campus Native Americans who "somewhere in their makeup are evidently ashamed of their beautiful Indian blood to the point that the word 'Indian' incenses them when it reminds them of what they are," she concluded with these emotive words: "We feel, as Indians, we are being crucified by our very own and will end with a prayer, 'Forgive them, oh Lord, for they know not what they do!"

Rumblings in the 90s

The Stanford Review does not find itself accused of racism for the first time today. The Review has in the past endorsed the Indian and taken stances that could have been construed as bellicose, jingoistic, or racist.

The Review published an unsigned editorial from November 1, 1992, titled "Bring Back the Indian." It argued that a majority of alumni wanted to return the Indian to its former status as mascot and that the "Official party line has thus far been a series of diatribes reaffirming a fanatical commitment to 'social change' through mind-numbing boredom. To them [the administration], the Indian is just one more casualty in their jihad to eradicate Eurocentrism, lookism, logocentrism, and anything else they may find distasteful at the moment." The Review has long published a short featurette on its second page called "Smoke Signals," similar to Newsweek's "Conventional Wisdom,

which features brief one or two sentence comments on various campus figures, programs or events. A caricature of the Indian particular to the Review, known as the "Chief" (shown above), has sporadically adorned the top of this weekly feature. The decision of whether to use the caricature or some other depiction has been made by each individual editor. The Review has received heavy criticism for this depiction and its support of the Indian. Our February 22, 1993 issue printed a letter from Russell Calleros, a junior in political science, asking us to "Have a little respect." He wrote: "Have a little compassion for the situation of Native Americans. As if it is not enough that they have been stripped of their people, their land, their religions, and their political autonomy, your recent support of the Stanford Indian threatens to strip them of their dignity. This is above mascots, above sports, above political correctness, and even above politics. This is about something called human dignity."

The Review did away with its "Smoke Signals" caricature in the winter of 1995. Michael Meyer, Editor-in-Chief, wrote that ultimately "the simple fact that someone might interpret the feature in a racist light, thus perpetuating the irrational and immoral beliefs of racism, was reason enough to change the feature." The caricature was replaced by a photograph of a Native American in traditional dress dancing around a fire. This later became a cartoon depiction of a camp-fire.

The Indian returned under Editor-in-Chief Stephen Cohen in early 2004 in Volume XXXII. The Chief was last used under Editor-in-Chief Ben Guthrie, in Volume XXXIV. He defended his choice thus: "The Chief should not be interpreted as a sign of disrespect for modern day Native Americans but rather as a sign of our support for a benign and cherished Stanford tradition and as a sign of defiance to the monomaniacal political correctness movement. Since the use of the Indian mascot for sports teams is frequently criticized for promoting the stereotype of Indians being war-like savages, the Review would like to do its part to counter this pejorative conception by promoting the view that the Indian is a paragon of wisdom and perspicacity, a shrewd and discerning arbiter of world affairs and campus events. Seen in this light, how can one object to the inclusion of the Chief in Smoke Signals?" (3/1//2005)

The Chief has not re-appeared in Alex Medearis and Ryan Tracey's volumes.

Rob's comment

Showing a wild-eyed, big-nosed Indian killing a bear (a protected species) or a Bear (a UC Berkeley rival) isn't racist or offensive or at least unpleasant? Sure it is.

Related links

Team names and mascots

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.