From a book review in the LA Times, 2/17/02:

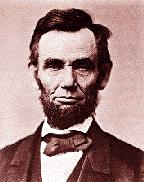

Why He's Called Honest

LINCOLN'S VIRTUES: An Ethical Biography, by William Lee Miller. Alfred A. Knopf: 522 pp., $30.

By DINESH D'SOUZA

*

Slavery is an ancient institution that has existed in just about every known society. For millenniums, slavery needed no defenders because it had no critics. The West is the only civilization that developed a principled campaign to end slavery. This campaign was supremely difficult in the United States because slavery was the cornerstone of the Southern way of life, and educated opinion in the South convinced itself that slavery was not a necessary evil but a "positive good."

In this grave situation, the notion that slavery could be ended and the nation kept together seemed utterly fanciful. Such a mission required a "philosophical statesman" of the kind that democratic societies rarely produce. He had to have deep intelligence, not of the epideictic sort but something closer to wisdom. The times demanded a man of moral imagination who understood that slavery was not simply a political but also an ethical issue: It involved the basic distinction between right and wrong. At the same time, a pure philosopher or saint was not suited for the task, because neither has the inclination nor aptitude for public leadership and democratic politics. Urgently required was a thinker and a moralist who also knew how to lead and when to act, in order that his great principles might be realized.

In Illinois, there was such a man.

William Lee Miller's "Lincoln's Virtues" is distinguished by its claim to be an "ethical biography." At one level, this is a quixotic enterprise. After several attempts to plumb the sources of Lincoln's moral development, Miller announces his "discovery" that "Lincoln was human, he was not born on Mount Rushmore ... he acquired such moral distinction as he did by deliberate effort over time, and [his] moral excellence never was or would be anything like perfection." Well, I could have figured that out without reading the book.

Miller's "ethical biography" does have one great value, however. It shows how Lincoln translated his moral principles into policy in the confused and disputatious theater of democratic politics. The author of "Arguing About Slavery," Miller begins with what may be termed the "Lincoln myth." How odd it is, he writes, that an "unschooled" politician "from the raw frontier villages of Illinois and Indiana" could become America's greatest president and one of the most admired and loved figures of mankind. "He was the myth made real," Miller writes, "rising from an actual Kentucky cabin made of actual Kentucky logs all the way to the actual White House."

Although Miller fully embraces the Lincoln myth, he shows that the author of this myth is Lincoln himself. Asked to describe his early life, Lincoln answered with reference to Thomas Gray's poem, "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard": "the short and simple annals of the poor." Lincoln disclaimed great aspirations for himself, noting that if people did not vote for him, he would return to obscurity, being used to disappointments. These pieties are inconsistent with what Lincoln's law partner, William Herndon, said about him: "His ambition was a little engine that knew no rest." Miller recognizes that even great ambition, of the kind that Lincoln harbored, is natural to a politician and favorable to democracy as long as it seeks personal distinction by promoting the public good through constitutional means.

Of course, Miller is aware that there are influential bodies of scholarship that criticize and even denounce Lincoln. What these critiques share is that they deny that Lincoln respected the law and that he was concerned with the welfare of all. The Southern school, epitomized by the late Mel Bradford, holds that Lincoln was a self-serving tyrant who never cared much about slavery but destroyed half the country to serve his Caesarean ambitions. In the view of these neo-Confederates, the Civil War was driven primarily by economic motives: It was the "war of northern aggression." In California, we may view these claims as crass attempts to justify the unjustifiable, but many Southerners do not. Surprisingly, Miller, who teaches at the University of Virginia, pays virtually no attention to the Southern school.

Miller's main concern is with what may be termed the "liberal school." This group, composed of left-wing scholars, African American activists and civil libertarians, is harshly critical of Lincoln on the grounds that he was a racist who didn't really care about ending slavery. The indictment against Lincoln is a familiar one: He didn't oppose slavery outright, only the extension of slavery into the territories; he said that if he could save the Union without freeing a single slave, he would do it; he opposed laws permitting intermarriage and even social and political equality between the races. Miller is very anxious to dispel these anxieties so that liberals can reclaim Lincoln as one of their heroes.

To his credit, Miller does not attempt to excuse Lincoln's opinions and actions by proclaiming him a "man of his time." After all, there were several persons of that time, notably the Grimke sisters and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, who forthrightly and unambiguously attacked slavery and embraced abolition. Miller cites Sumner saying that there are issues on which political men can and should compromise but that slavery is not such an issue: "This will not admit of compromise. To be wrong on this is to be wholly wrong. It is ... our duty to ... defend freedom, unreservedly, and careless of the consequences."

Careless of the consequences. Here we have that recognizable thing, the voice of Lincoln's contemporary liberal critics, who (whether they know it or not) are the philosophical descendants of Sumner. One cannot understand Lincoln without understanding why he agreed with Sumner's goals while consistently opposing the strategy of the abolitionists. The abolitionists, Lincoln saw, were not primarily concerned with restricting or ending slavery. They were most concerned with self-righteous moral display. They wanted to be in the right and—as Sumner declares—forget the consequences. In Lincoln's view, abolition was a noble sentiment, but abolitionist tactics, such as burning the Constitution and advocating violence, actually advanced the cause of slavery.

It is the burden of Miller's biography to show why Lincoln's understanding of slavery and his strategy for defeating it were superior to Sumner's and his modern-day followers. In this, Miller is partly successful, mounting, as he himself admits, a "quasi-defense" of Lincoln. Miller vindicates Lincoln of the charge that he didn't really care about slavery. For Lincoln, slavery was the very touchstone of political morality: "If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong." Lincoln authored some of the most telling and memorable lines against slavery, for example: "Although volume upon volume is written to prove slavery a very good thing, we never hear of the man who wishes to take the good of it by being a slave himself!"

Miller effectively shows that the statesman, unlike the moralist, cannot be content with making the argument: He must find a way to implement his principles to the degree that circumstances permit. This is the key to understanding Lincoln. He always found the common denominator between what was good to do and what the people would go along with. In a democratic society, this is not just a matter of prudence. It is the only legitimate way of advancing a moral agenda.

What Miller does not fully appreciate is the consummate skill with which Lincoln deflected the prejudices of his supporters without yielding to them. During his debates with Stephen Douglas in the race for the Illinois Senate, Douglas repeatedly accused Lincoln of believing that blacks and whites were intellectually equal, of endorsing full political rights for blacks and of supporting "amalgamation" or intermarriage between the races. If these charges could be sustained, if widespread numbers of people believed them to be true, then Lincoln's career was over. Even in the free state of Illinois—as throughout the anti-slavery North—there was widespread opposition to full political and social equality for the races.

So how did Lincoln handle this difficult situation? He used a series of artfully conditional responses. "Certainly the Negro is not our equal in color—perhaps not in many other respects; still, in the right to put into his mouth the bread that his own hands have earned, he is the equal of every other man. In pointing out that more has been given to you, you cannot be justified in taking away the little which has been given him. If God gave him but little, that little let him enjoy." Notice how little Lincoln concedes to prevailing prejudice. Lincoln never acknowledges black inferiority; he merely concedes the possibility. And the thrust of his argument is that even if blacks are inferior, this is no justification for taking away their rights.

Or again, facing the charge of racial amalgamation, Lincoln says, "I protest against this counterfeit logic which concludes that because I do not want a black woman for a slave, I must necessarily want her for a wife." Lincoln is not saying that he wants, or does not want, a black woman for his wife. He is neither supporting nor opposing racial intermarriage. He is simply saying that from his anti-slavery position, it does not follow that he endorses racial amalgamation. Elsewhere Lincoln turned anti-black prejudices against Douglas by saying that slavery was the institution that had produced the greatest racial intermixing and the largest number of people of mixed race offspring.

Miller's book is a defense of Lincoln, but it is not a full-throated defense, and it falls short of the serious treatment that a man of Lincoln's depth and greatness demands. Despite its flaws, "Lincoln's Virtues" is a useful addition to the library of Lincoln books because it tackles a familiar subject from an unusual angle, giving appropriate centrality to Lincoln's moral convictions.

*

Dinesh D'Souza is Rishwain Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and the author of, most recently, the forthcoming "What's So Great About America."

Copyright 2002 Los Angeles Times

More on Lincoln

How Lincoln's Army 'Liberated' the Indians

Lincoln's Gettysburg PowerPoint presentation

Related links

Fun 4th of July facts

A shining city on a hill: what Americans believe

America's cultural mindset

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.