An excellent article on the origin of people in the Western Hemisphere:

An excellent article on the origin of people in the Western Hemisphere:

An excellent article on the origin of people in the Western Hemisphere:

An excellent article on the origin of people in the Western Hemisphere:

Rediscovering America

The New World may be 20,000 years older than experts thought

BY CHARLES W. PETIT

Late in the afternoon last May 17, a tired archaeological team neared the end of a 14-hour day winching muck to the deck of a Canadian Coast Guard vessel. It was in water 170 feet deep in Juan Perez Sound, half a mile offshore among British Columbia's Queen Charlotte Islands. For four days, team members had fruitlessly sieved undersea mud and gravel. Then, in the slanting light of sunset, a deckhand drew from the goop a triangular blade of dark basalt. Its sharp edge and flaked surface said this was no ordinary rock. Someone long ago sculpted it into a knife or other cutting tool.

When Daryl Fedje, an archaeologist for Canada's national parks system, saw the 4-inch artifact, his jaw dropped in amazement: "I immediately recognized it as made by humans." For years Fedje has led efforts to find prehistoric evidence of human occupation in the misty, fiord-laced archipelago. This stone meant that people lived at a spot directly under the ship well before the end of the Ice Age, at a time when the sea level was far lower than today.

The bit of basalt is just one stone. But from Alaska to near the tip of South America, bits of just such intriguing evidence are emerging that suggest the standard textbook story—that humans first settled the Americas by pouring down from Alaska about 12,000 years ago—is wrong, perhaps very wrong. People may have gotten here thousands to tens of thousands of years sooner, over a longer period of time, by a wider variety of routes, and with a more diverse ancestry. If this proves true, it will force a rethinking of the whole concept of America: a land whose human history may be three times longer than imagined, and one where Columbus would have been just one of the last of many waves of "discoverers."

"The bottom line is that people could have reached here a long, long time ago," says Dennis Stanford, chairman of the anthropology department at the Smithsonian Institution. Stanford is among a growing number of scientists advancing the still heretical belief that the first North Americans did not walk over in one main migration but came much earlier, and by boat. Under fire is the time-honored "Clovis-first" theory, named after a site in New Mexico where big, stone spear points were found in the 1930s (story, Page 60). The artifacts were left by a mammoth-hunting culture that appeared in North America a little more than 11,000 years ago. The Clovis people were real, but the standard textbook lessons about them may well be wrong. It now appears that they were not the first in the New World. "I think we're in a whole new ballgame of discovery about who the first Americans were and when they got here," Stanford says.

That would spell the end of the heroic saga generations of schoolchildren have learned—of a great invasion of big-game hunters showing up on a virgin landscape. The peopling of the Americas is beginning to look more like a continuation of another, even grander, saga: the human occupation of the Old World that started perhaps 100,000 years ago. The peopling of Europe and Asia was an expansion featuring multiple migrations and an ebb and flow of cultures that, it now appears, may have washed into the Americas in a series of waves starting well before Clovis times, perhaps as early as 30,000 years ago.

Scholarly rejection. Despite the primacy of the Clovis-first tale, some scientists never could quite embrace it. Over the years, hundreds of sites have been touted as older than the 11,200-year-old early Clovis sites, including Calico in San Bernardino County, Calif., endorsed in the 1960s by famed African anthropologist Louis Leakey as possibly more than 200,000 years old. But each time, at Calico and elsewhere, parades of outside experts said the "tools" were natural stones, or the dates were wrong, or supposedly human bones weren't human, or the charcoal was from a naturally caused wildfire, not a man-made hearth, or all that and more. The sites "have gotten their 15 minutes of fame, then disappeared into obscurity," said James Adovasio, professor of archaeology at Mercyhurst College in Erie, Pa.

Adovasio has his own tale of scholarly rejection. Since 1973 he has led excavation of the Meadowcroft Rockshelter, a 43-foot-high jutting cliff that provides protection from rain along its base. It looks out on Cross Creek, in rugged country 30 miles southwest of Pittsburgh. The landowner, Albert Miller, whose family has had the property since 1795 and operates a colonial-era museum there, called archaeologists in the early 1970s to investigate his hunch about Indian traces under the overhang. Miller's instincts were right. "Everybody and his brother stopped here," marvels Adovasio. Using razor blades to peel layers away, his crews have uncovered a rich trove of relics—20,000 stone tools, woven goods, nearly a million animal bones, and 300 fireplaces loaded with charcoal, making it easy for scientists to calculate dates. (Scientists estimate the age of charcoal and other organic material by measuring how much radioactive carbon-14 it contains. Living things absorb this isotope from the atmosphere; when they die, the radiocarbon begins to decay away. Although new studies suggest that solar variations throw the scale off slightly—11,000 radiocarbon years may be closer to 13,000 actual years, for instance—radiocarbon dating is still the gold standard for archaeological dating.) The cave was on a highway for traders, hunters, and migrants moving to and from the Ohio River Valley to the West. "If you were out camping and saw this place, this is where you'd stop, too," Adovasio says. Every accepted cultural period in Indian history and prehistory is represented: the contemporary Iroquoian Seneca; earlier and closely related "woodland" societies that reach back 1,000 years; the so-called archaic groups to around 8,500 years ago; and Paleo-Indians, including the Clovis big-game hunters, to about 11,000 years ago.

Trouble came when Adovasio began saying in the late 1970s that charcoal from human-made fire pits deep in the excavated floor of the shelter carried dates going back more than 14,000 years, with some indications approaching 17,000 years. He ran into what he calls the "Clovis curtain" of resistance. Critics told him the charcoal that he presumed came from wood may actually have been contaminated by ancient coal or carbon in the local sediments, which would carbon-date much earlier. Adovasio retorts that what he calls the "Clovis mafia" peculiarly rejects only dates at his site that are older than Clovis but not younger material. Contamination would skew ages for everything, he points out, not just for the finds that run counter to standard theory.

Accumulating evidence. But after years of being almost alone as a challenger of Clovis, Adovasio suddenly has company. Similar deposits are being reported by archaeologists at sites throughout the Americas, including one called Cactus Hill, in coastal Virginia. That project's leader, Joseph McAvoy of the privately supported Nottaway River Survey in Sandston, Va., can't discuss his newest findings because he's under a gag order from the National Geographic Society, which is helping pay for the excavation. But in a 1996 report, McAvoy described his discovery of possible pre-Clovis tools that Adovasio says look a lot like his at Meadowcroft.

Evidence also has shown up in Wisconsin. For 10 years, David Overstreet, director of the Great Lakes Archaeological Research Center in Milwaukee, has excavated two mammoth butchery sites that he says are at least 12,500 years old, and where stone tools lie among giant bones and long, curved ivory tusks. Nearby are bones of two more of the extinct elephants, 1,000 years older, bearing what appear to be the distinctive cut marks made by people chopping out meat for food. The roughly shaped tools look nothing like the precisely grooved Clovis points. Overstreet figures that by the time any corridor through the glaciers opened, somebody had already been living for a few millenniums along the ice front, hunting the megafauna of the plains south of it.

But the big break that persuaded many to rethink the conventional theory has come thousands of miles from Clovis in Monte Verde, Chile. There, archaeologist Tom Dillehay of the University of Kentucky has, for 20 years, been excavating wood, bone, and stone tools from rolling pasture land. Last year he was joined by a blue-ribbon group of archaeologists, including many who were skeptical of Dillehay's long-controversial assertions that the artifacts probably are at least 12,500 years old. The expert panel viewed the site and wound up agreeing with Dillehay: The tools bore no resemblance to those of the vanished Clovis culture. Dillehay and his Chilean colleagues now are planning more excavation to explore hints that people were at the site as many as 30,000 years ago.

Some scientists say one needs only to study modern Indians to conclude that their ancestors got here before Clovis time. One hint is in genetic material passed down only from mothers to offspring, called mitochondrial DNA. Such genes carry a molecular clock—if a single population splits into isolated groups, the buildup of random, but distinct, mutations allows geneticists to estimate how long the original groupings have been separated. "For the last five years, the genetic evidence has been saying early, early entry" into the Americas, says Theodore Schurr, a geneticist at Emory University in Atlanta. When Schurr counts the mutations accumulated among American Indians, the molecular data are consistent with departures from Asia between 15,000 and 30,000 years ago. The analysis revealed three distinct families of mutations common among American Indians and found elsewhere only in Siberia or Mongolia. Strangely, about 3 percent of Native Americans also have a genetic trait that occurs elsewhere only in a few places in Europe. This could mean either that some Asian populations migrated both west, into Europe, and east to the Americas, or that Ice Age Europeans may have trickled into the New World many thousands of years ago, perhaps by skirting the Arctic ice pack over the North Atlantic.

Linguists offer a remarkably parallel analysis. Johanna Nichols, a professor in the Slavic languages department of the University of California—Berkeley, counts 143 Native American language stocks from Alaska to the tip of South America that are completely unintelligible to one another, as different as Gaelic, Chinese, or Persian are from one another. The richest diversity of languages is along North America's Pacific coast, not along the Clovis group's supposed inland immigration route. California alone has dozens of dissimilar languages.

It takes about 6,000 years for two languages to split from a common ancestral tongue and lose all resemblance to each other, Nichols says. Allowing for how fast peoples tend to subdivide and migrate, she calculates that 60,000 years are needed for 140 languages to emerge from a single founding group. Even assuming multiple migrations of people using different languages, she figures that people first showed up in the Americas at least 35,000 years ago. If archaeologists haven't found proof of such ancient events, well, "as a linguist, that's not my problem," Nichols shrugs. Clovis-first, she says, is "not remotely possible."

The glacier highway. Even some geologists are taking a punch at Clovis primacy. "Recent work shows that the corridor [through the glaciers] was not open until 11,500 years ago," says Carole Mandryk, a geologist at Harvard University. "That is a pretty major problem for ideas that it was a highway for colonization within a few centuries." Mandryk's studies indicate the corridor would have been nearly impassable for a century or more, with little game or edible vegetation, and vast, boggy wetlands. "The corridor is 2,000 miles long," Mandryk says. "Let's say you are two young guys, and you carry as much food as you can, and you walk as fast as you can. It still takes you six months to get through. And then you run around and kill a lot of animals. Then you have to go back and tell everybody else to get their families and come on down." She blames the persistence of the Clovis-first theory on these "macho gringo guys" who "just want to believe the first Americans were these big, tough, fur-covered, mammoth-hunting people, not some fishermen over on the coast."

Just this summer, one longtime Clovis-firster abandoned the idea. For years, Albert Goodyear, associate director for research at the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology, has calmly supported Clovis. Monte Verde shook him just a bit. So in July, along the Savannah River at a site called Topper, he decided, just to be responsible, to keep digging below sediments dated to the Clovis era. All of a sudden, "we found a tool, and then another." For a solid yard down, scores of blades, flakes, and other human-crafted artifacts turned up. Goodyear told students and volunteers, yes, those sure look older than Clovis. "I had a paradigm crash right there in the woods. I felt like Woody Allen, like I had to turn and say to the audience, 'Why am I saying these things I'm not supposed to believe?' Just five years ago, nothing new was possible in American prehistory, because of dogma. Now everything is possible; the veil has been lifted."

Finds such as Goodyear's are cause for celebration among long-suffering Clovis doubters. "The Clovis-first model is dead," proclaims, with some overstatement, Robson Bonnichsen, director of the Center for the Study of the First Americans at Oregon State University. He has made the center a clearinghouse for information about alternatives to Clovis-first. "I've felt there were people here more than 12,000 years ago from the start," he says. "We're finally getting the evidence to back that up."

But not all Clovis-firsters are throwing in the towel. "I find Monte Verde quite unconvincing," says Frederick Hadleigh West, director of archaeology at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass., and editor of a recent 576-page compendium on the archaeology of Alaska and eastern Siberia. "There is really no credible, undisputable evidence of anything prior to Clovis. But with Clovis you have an undeniable outburst of people, appearing on an empty continent, spreading like mad. There is absolutely no [incontrovertible] evidence of people coming into the New World before 12,000 [years ago], or 15,000 if you keep them in Alaska." For Monte Verde to unseat Clovis-first, he said, "would be like Sudan conquering the United States."

Not enough stuff. Another longtime Clovis-first adherent, geoarchaeologist Vance Haynes of the University of Arizona, was among the experts who last year endorsed the 12,500-year-old Monte Verde finds as legitimate. But he argues there isn't enough evidence to support the Meadowcroft and Cactus Hill material. And even if he can't rule out Monte Verde, Haynes says it should take more than one site—scientific fallibility being what it is—to refute the primacy of Clovis. "It has just six artifacts [stone tools]. If it is as old as it looks, and the dates do look solid, then there should be others like it. Until we find those, there are still questions."

Those questions are profound. The Clovis people were real, but where did they come from? No tools in Alaska or Asia seem to foreshadow their distinctive fluted spear points. And how and when did people get to South America? Many authorities believe it would have taken people 7,000 years to have reached southern Chile from Alaska. Others say it could have been faster by boat. But the fact remains that while Clovis traces are abundant, evidence of older cultures is terribly hard to find. "Where are they?" asks David Meltzer, an archaeologist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, who thinks the Monte Verde dates are accurate but remains puzzled. "I don't know. That is the exciting part about all this."

No single, simple theory has yet emerged to replace Clovis-first. But some of the stories that are emerging in attempts to answer those questions are as arresting as the original Bering land bridge and inland invasion saga. For one, there's the mystery of the people who chipped that basalt point Daryl Fedje's team found this spring off Canada's Pacific shore.

The recovery of the tool was no random plunk with a bucket into the sea floor. Fedje and marine geologist Heiner Josenhans of the Geological Survey of Canada spent four years mapping the sea floor around the Queen Charlotte Islands. An array of sonar receivers revealed it as though it were viewed from a low-flying plane without any distortion from water; computer software let the researchers soar and loop low at will, as in a video game, among now-submerged valleys and hills. Fedje knew that if people were here more than about 10,000 years ago, they lived on that farther shore, near salmon, seals, shellfish, and other key food sources. Tribal lore of the present-day Haida nation includes tales of times when the islands were far larger and surrounded by grassy plains, and of subsequent, fast-rising oceans when a supernatural "flood tide woman" forced the Haida to move their villages to higher ground. Geologists agree with the traditional Haida view of their past: The islands were twice as large 11,000 years ago, and the Pacific rose more than an inch per year for a millennium after that, as the glaciers melted. The Haida have been on the islands, which they call Haida Gwaii, a very long time. Whether it was their ancestors who left the stone point is unknown. Fedje and Josenhans are now poring over the maps of the vanished landscape, hoping to return in the next year or so, if they get the funding, with remotely controlled submarines to prowl the places some of the earliest Americans may have called home.

But the origins of these coastal people remain a mystery. It seems unlikely that Clovis hunters could have scampered west along the ice sheet's southern edge, transformed themselves into a seagoing, salmon-catching, seal-spearing culture, and occupied Haida Gwaii within a few centuries of arrival. Hence the favorite hypothesis, first proposed more than 20 years ago but now supported by the Smithsonian's Stanford, Harvard's Mandryk, Fedje, and many others, is that many people migrated to the New World along the coast instead of overland. Travel may have been in small boats, perhaps covered in skin like traditional Eskimo and Aleut kayaks. If, as seems likely, people migrated during the height of the last Ice Age, between about 25,000 and 12,000 years ago, they would have avoided glaciers calving into the sea. "There was boat use in Japan 20,000 years ago," says Jon Erlandson, a University of Oregon anthropologist. "The Kurile Islands [north of Japan] are like steppingstones to Beringia," the then continuous land bridging the Bering Strait. Migrants, he said, could have then skirted the tidewater glaciers in Canada right on down the coast.

Evidence of other maritime cultures along the West Coast is coming in fast. Erlandson has uncovered remains of seagoing peoples who lived more than 10,000 years ago in the Channel Islands off Southern California. And last month, other scientists reported that two sites in Peru reveal people were living along its coast, subsisting almost entirely on seafood, nearly 11,000 years ago, too long ago for the Clovis migration to have gotten there and spawned a maritime way of life.

The Americas are big continents. Perhaps the earliest people just weren't very numerous and left little mark of their passing. Or, maybe most of them lived out on the then exposed continental shelf, retreating inland only when the end of the Ice Age raised the sea. Perhaps these people, driven inland, gave rise to the Clovis hunters. Well below the waves and under millenniums' worth of cold sediment, may lie the footprints, remains of meals, and discarded tools and campfire pits of a lost world. It is, indeed, a whole new ballgame in the search for the first Americans.

MAMMOTH HUNTERS

They came from the north

The standard explanation of human arrival in the Americas is a stirring tale with mythic overtones, of fur-clad big-game hunters marching out of the far, frozen north to conquer a New World, an Eden whose immense beasts had never before seen human beings. This Clovis-first theory is under assault but has not yet crumbled, as scientists examine scanty evidence to decipher how North and South America were first occupied. The Clovis-first theory, named after an archaeological site near Clovis, N.M., proposes that, perhaps 15,000 years ago, Arctic-adapted peoples moved across a 1,000-mile-wide land bridge where the shallow Bering Strait today separates Alaska from Siberia. After being bottled up for a few thousand years by glaciers south of Beringia—the name given the combined land mass of Alaska and northeastern Siberia—about 12,000 years ago this vanguard moved down into what is now Alberta, traversing an ice-free corridor that opened through the glaciers just east of the Canadian Rockies as the Ice Age waned. Splitting into smaller groups and developing new cultures as they went, and bearing large families supported by the vast resources before them, these Paleo-Indians supposedly raced all the way to the tip of South America in 1,000 years or so. And, except for some later-arriving groups, including today's Inuits, or Eskimos, these people would have been the ancestors of nearly all of today's Native Americans.

Heavy artillery. Clovis-first arose from discoveries, starting in the 1920s, of chipped and shattered bones of bison and mammoths. These bones were the first proof that people had arrived in time to see, and kill, the last great beasts of the Ice Age, and that hunting may have contributed to the animals' extinction.

Distinctive long spearheads, called Clovis points after the New Mexico site where they were discovered, have been found with bones of prey dated as much as 11,200 years ago. Hundreds of Clovis sites have been identified throughout North America, implying that wherever the hunters came from, their culture exploded across the landscape with astonishing rapidity. The robust Clovis points bear grooves or "flutes" carved in their bases where they attached to wooden shafts. Propelled with powerful atlatls, or throwing sticks, the stone-tipped spears served as heavy artillery as the newcomers butchered their way across North America's great plains in a virtual blitzkrieg.—C.W.P.

KENNEWICK MAN

A fight over the origins of ancient bones

The hunt for the first Americans does not go without resistance: Witness the bitter court battle over the mysterious "Kennewick Man."

The central figure is a 9,300-year-old skeleton that has been packed in sealed plastic bags in a government lab for more than two years. Frustrated scientists, hoping desperately to scrutinize its bones and analyze its DNA, are up against an American Indian group that believes the bones belong to an ancestor and should be reburied with no further study.

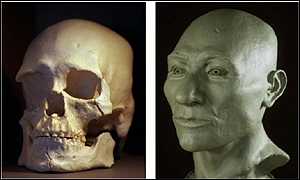

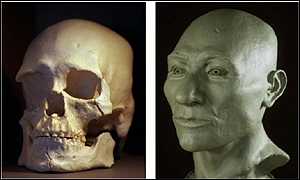

It is clear that the remains, named after a town near the spot on the Columbia River in southeast Washington where two college students found them in July 1996, are of a slender, middle-aged fellow bearing scars of a very rough life, including multiple fractures, a crushed chest, a withered arm, and a healed skull injury. It is the most complete and among the oldest of skeletons found in North America.

When the bones were found, the Benton County coroner asked James Chatters, a local forensic anthropologist, to examine what looked like a possible homicide victim. Chatters thought the bones were older than that, but he thought they might belong to a 19th-century settler. Then Chatters made what he now says was a big mistake: He labeled some of the man's facial features "Caucasoid," based on the fact that the narrow face, long head, and jutting chin were not an Indian's typically broad face, prominent cheekbones, and round head.

But when Chatters spotted a stone projectile buried in a hip bone, he realized the bones were much older—that type of point disappeared from the region at least 4,500 years ago. A quickly arranged carbon dating test revealed the bones' age, and significance. Word got out, and all hell broke loose. Some people of European ancestry claimed Kennewick Man as a long-lost brother, even though the "Caucasoid" label now looks wrong. Instead, Chatters and physical anthropologists say, Kennewick Man looks more Asian than anything—a bit like the ancient Ainu people of Japan. These bones argue that the people who lived in the New World 9,000 years ago were more physically varied than today's Indians.

Conflict. The legal battle over Kennewick Man was prompted by a 1990 federal law, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, under which Indian relics found on U.S. property are to be offered to tribes affiliated with them. The bones were found on Army Corps of Engineers land. After Chatters had studied the bones for two weeks, the corps locked them up and offered them to the local Umatilla Indians, who said they would rebury them without further study. "Our elders have taught us that once a body goes into the ground, it is meant to stay there," said Armand Minthorn, a member of the tribe's board of trustees, who is sure the man is an ancestor. "We do not believe that our people migrated here from another continent, as the scientists do."

Eight scientists, including Chatters and two from the Smithsonian Institution, sued the Corps of Engineers to block reburial, arguing that there is no evidence the bones are related to any living Indians. That is where things stand. A federal judge has ordered the Corps of Engineers and the Department of the Interior to figure out who gets the bones. It may be a year before the dust settles.

Chatters said he has been painted as some "evil person" by Indian leaders. "They say it is their history, but I think when people start to try to control their own history and deny anybody from studying it, that's a mistake." Besides, his wife is partly of Indian ancestry, as are their three children. "It's my family history, too," he said.—C.W.P.

Related links

Kennewick Man, Captain Picard, and political correctness

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2008 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.