Endless Flights:

Endless Flights:

The Forgotten Astronaut

and His Friend

by Robert Schmidt

Former IWOSC Director of Publications Robert Schmidt writes about an earlier generation of Schmidts.

This is the true story of a down-to-earth businessman and a soaring

astronaut. They shared America's can-do pragmatism and its sky's-the-limit sense of vision. They were united by one thing: their

unquenchable love of flying.

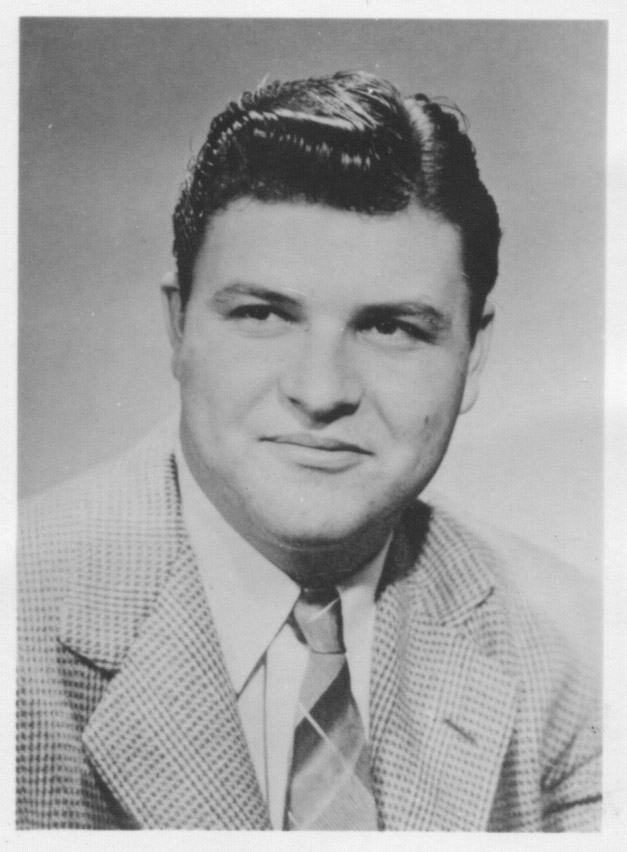

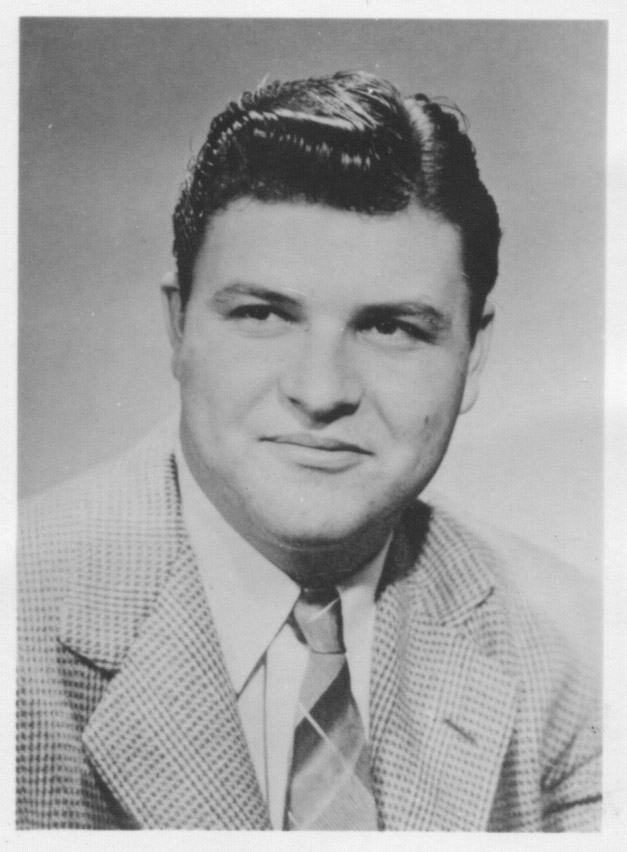

Bob Schmidt was born in Long Beach, California, in 1926. He was an

only child. Father Vernon was a civil engineer and entrepreneur,

mother Enid a school teacher who enjoyed travel. Perhaps because of

them, or because of the fledgling aerospace firms springing up around

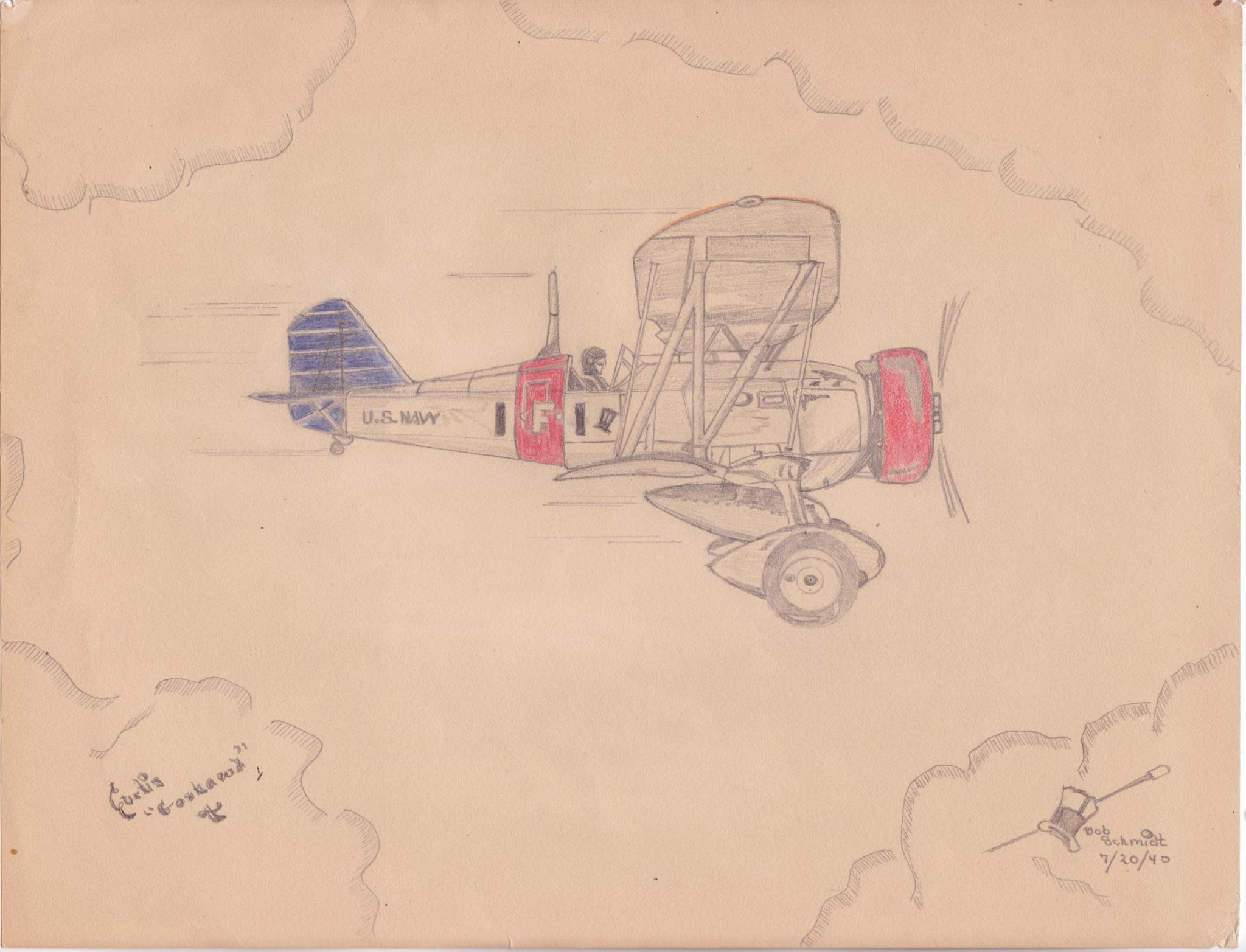

him, Bob cherished nothing more than those incredible flying machines.

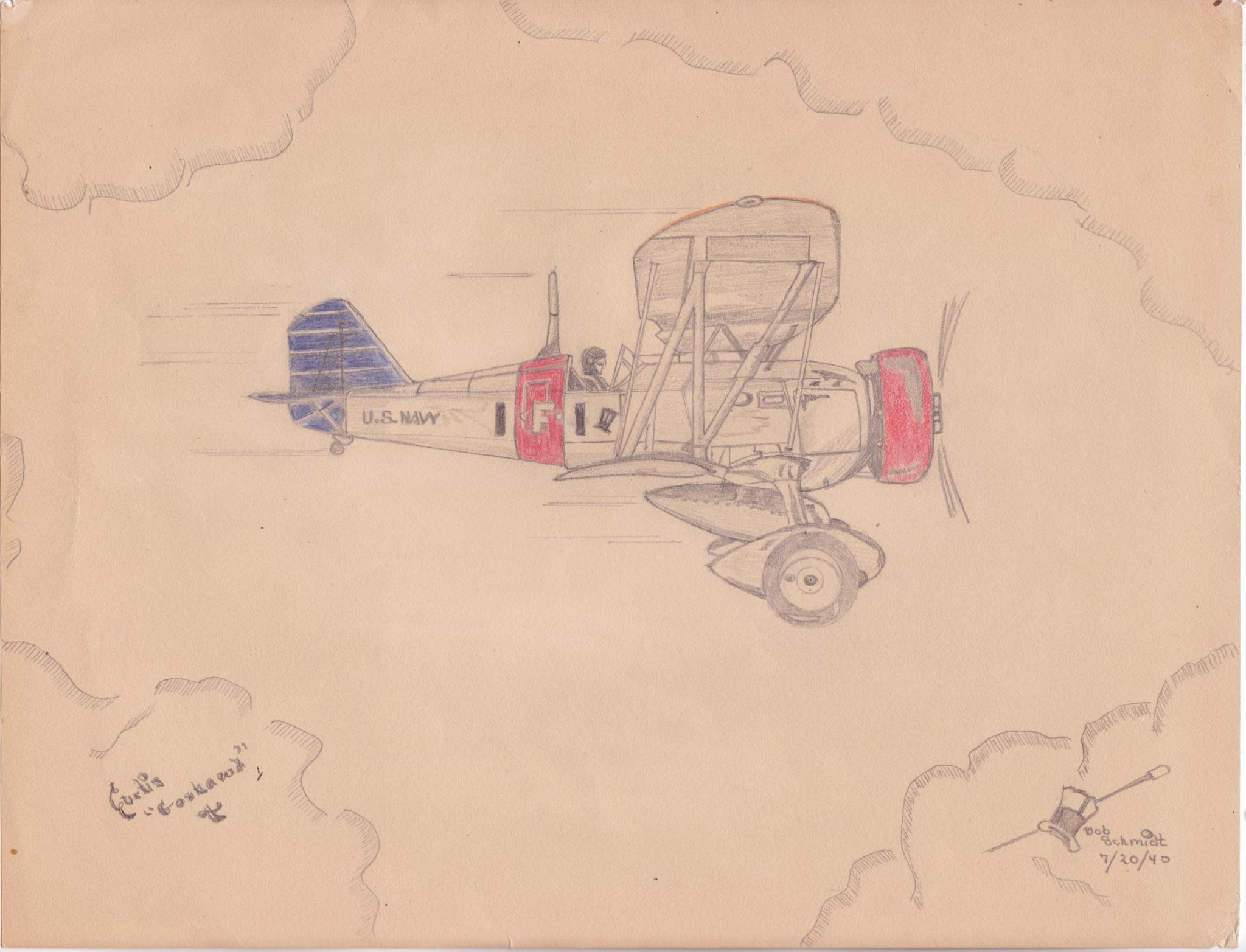

As a boy he spent hours building model airplanes. He ordered airman's

wings from a cereal box. He devoured the comic strip Tailspin Tommy.

When nothing else was available, he and his friends raced through the

neighborhood with arms outstretched and "engines" roaring.

Most of all Bob longed to be a pilot, but there was one hitch. Fate

had given him a birth defect, a shriveled mockery of a right arm.

Though he could run track and play trumpet in the band, he couldn't

grip a steering wheel in two hands. It was a serious impediment to his

plans.

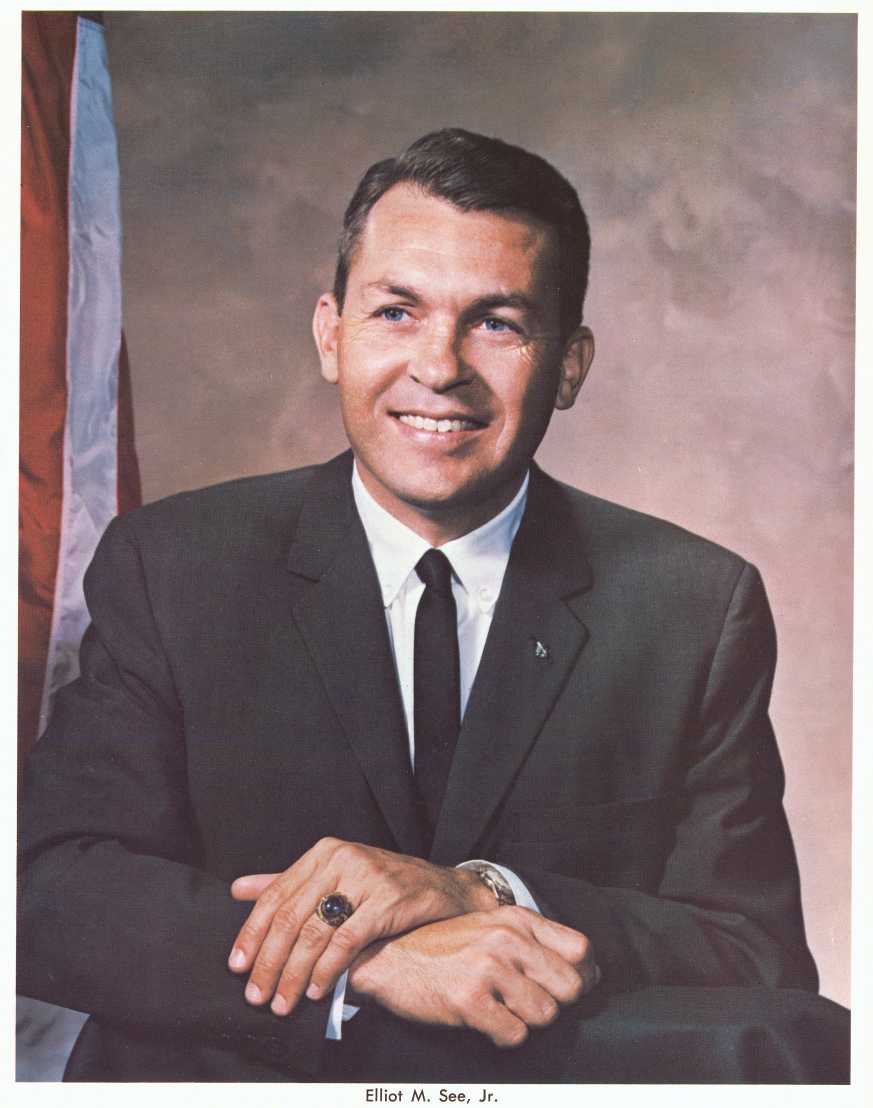

Meanwhile, Elliot M. See Jr. debuted in Dallas in 1927. From Elliot

Sr., an electrical engineer with years at General Electric, the lad

learned to appreciate technology and its marvels. From his mother

Mamie, a real estate agent active in civic circles, he gained a strong

sense of duty. From them and from God came his humble but firm

convictions.

While Bob was merely brilliant academically, Elliot was practically an

All-American. Five years as a Boy and Eagle Scout . . . the ROTC . . .

three years of Latin . . . president of the National Honor Society . .

. letters in boxing and rifle . . . Greek fraternities . . . the list

went on and on. Great things seemed in store for this young man.

But first there was a little matter of a world at war. Both boys

desperately wanted to help the Allies to victory. Bob, in particular,

saw this as his golden chance. Surely the Army needed anyone who could

fly. He would get his wings and win.

The Civil Aeronautics Administration, forerunner of the FAA, wouldn't

let anyone operate a plane near the coast. Undaunted, Bob found a

strip in Arizona where he could practice without pause. Many times he

took a six-hour-plus car or bus ride to Quartzsite, spent the weekend

flying, and wearily returned home.

After months of this, Bob earned his license on Sept. 11, 1944. He

immediately applied to the American and Canadian militaries. He even

tried the American Field Service and its air ambulance corps. Despite

the proof he could fly, no one would take him with his arm.

Disappointed, Bob decided the next best thing to piloting planes was

building them. He went to Stanford with the other 4Fs and majored in

engineering. But his father had died and he longed to be elsewhere, so

his grades fell precipitously.

In fact, he spent a term or two on academic probation before pulling

through. To his friends, this only proved his genius. No one else

could've studied as little as Bob did and still managed to graduate.

And he kept flying on the side. The war may have been a hindrance, but

it didn't prevent him from dropping toilet paper on Cal Berkeley in one

memorable flight. As any Stanford Indian could tell you, there were

enemies and then there were enemies.

Meanwhile, Elliot had joined the Merchant Marine Academy after one

semester at the University of Texas, Austin. Here he could both serve

his country and study his beloved engineering. A go-getter from the

word "go," he quietly made himself known. He became commander of the

Third Company, captain of the rifle team, and even chairman of the

cheerleading committee.

Though he sometimes joined his classmates for a night on the town, he

was a determined student. As soon as their marks were posted, he'd

check to see how he compared to the rest. Well enough, evidently, to

graduate within the top twelve of his class in 1949.

With all the ex-GIs in the hunt, work was hard to come by. Elliot, at

least, could follow his father to General Electric and get a spot in

Boston. Bob's path was more circuitous. After brief stints at the

Bremerton Naval Yard on Puget Sound and elsewhere, he wound up in

Beantown also. He was lured by thoughts of GE's J-47, the latest in

jet engines.

It was there, in GE's flight test engineering, that Bob Schmidt met

Elliot See. Working at adjoining desks, the two became fast friends.

When the department moved to Cincinnati they moved with it, renting a

house with two other teammates, Ray and Harry.

The foursome dated GE secretaries and held forth at their place out in

the country. A frequent guest at parties was Joe Flight Test, a dummy

stuffed with straw. In his cap and jacket Joe would sit on the porch,

greeting visitors with a jaunty stare.

Elliot had never given much thought to flying, but Bob infected him

with the bug. Soon, Elliot's passion for it was as feverish as Bob's.

Elliot took lessons and bought a Luscombe Silvair, the first all-aluminum plane, with Ray. They flew the small two-seater around Ohio

incessantly.

Elliot had never given much thought to flying, but Bob infected him

with the bug. Soon, Elliot's passion for it was as feverish as Bob's.

Elliot took lessons and bought a Luscombe Silvair, the first all-aluminum plane, with Ray. They flew the small two-seater around Ohio

incessantly.

Enjoying himself, Elliot buzzed low over neighbors, who shook their

fists in reply. He tried aerobatics the 65-horsepower motor couldn't

manage. He and Ray bet who could land closest to a handkerchief placed

on the airstrip. Elliot won more often.

Sometimes they flew cross-country--for instance, south to the beaches

near Tallahassee, where they'd land and lie on the sand getting

sunburned. On one trip to Michigan, Elliot wondered if he could fly

without instruments, and plunged the plane into a towering cloud. He

came out in a spiral dive before righting himself.

Perhaps because he was a devout Christian Scientist, he felt little or

no fear. Once he took up his girl, Marilyn, and the engine coughed

trouble. No problem, said Elliot, and aimed for the proverbial

farmer's field. Unfortunately, he cut it a bit too close. The tail

wheel snagged on a power line, upending the plane.

Though the pair weren't hurt seriously, Elliot's face was a mess. In

the hospital, Bob and the others told him he needed plastic surgery.

Elliot refused, citing his religious principles. His friends told him

Mary Baker Eddy wouldn't hack it this time, and Elliot relented.

While their off-hours were full, Bob was growing bored on the job.

Though he literally could handle the nuts and bolts of engineering, his

connection to planes had always been visceral, not mechanical. Aloft,

he was in control, far from the people who had slighted him because of

his handicap.

Realizing this, he resolved to follow his father into business.

Naturally, he aimed high--at the premier B-school, "Hahvud." Bob's

girlfriend Naomi thought he was crazy to apply with his suspect

Stanford grades. But experience and ambition counted more than

academics, so he got in. He waved the acceptance letter at her with a

smug air of satisfaction.

Ensconced at the Cambridge campus, Bob was finally in his element. He

held bull sessions with his classmates, including Harry and Ray, whom

he'd persuaded to join him. His triumph was an independent study

analyzing the future of jet engines. He interviewed airline presidents

around the nation, and GE was so impressed it paid his expenses.

He graduated with honors in 1954. With his research as his calling

card, he was ready to take the industry by storm. His plans had

transmuted into something more practical.

But the dream still lived, because Elliot had adopted Bob's vision of

becoming a professional pilot. He knew he needed thousands of hours of

air time to qualify. The best--and cheapest--place to get them was in

the Navy, so he had left his buddies to join.

For three years he flew the naval trainers with as much gusto as his

Luscombe. Landing on cramped aircraft carriers in the middle of

roiling seas was dangerous, so his handkerchief practice came in handy.

When he visited his friends, he regaled them with stories of death-defying incidents.

Despite his one crash, Marilyn must've forgiven him, because she

eventually married him. When Elliot couldn't make Bob's wedding, to

the same skeptical Naomi, he apologized in a telegram. It was signed

"The Phantom Pilot."

Bob began a career as a budding aerospace executive and family man.

His responsibilities meant less flying, but Elliot more than made up

for that. He left the Navy, earned a Master's in engineering from

UCLA, and returned to GE as a test pilot. He pushed planes through the

envelope at Edwards Air Force Base.

When Bob joked that Elliot should become an astronaut, Elliot chuckled

and said he'd already applied. To everyone's surprise, NASA chose him

as one of nine trainees out of 253 applicants. He was the oldest of

this second group of astronauts, which included Pete Conrad and Jim

Lovell, and one of two civilians. The other was a guy named Armstrong.

Elliot moved to Houston and dug in. He had the engineering depth to

master the systems on which his life would depend. The science of

space flight was what interested him, not Cold War competition. In an

essay for Life magazine, he waxed eloquent about the lighting

conditions facing moon landers. At a barbecue, he brought his own food--unappetizing cubes NASA asked him to try.

Like the other astronauts, he was committed to the program, but he

never lost his droll sense of humor. In a news release he carried on

about Apollo's technical challenges, such as producing water by fuel

cells. He concluded that "the potability of this water is now being

tested with mice. Apparently it is all right, but I have heard that

one of the mice became pregnant."

The men played as hard as they worked, but not Elliot. He was devoted

to his wife and kids. He frowned on his colleagues' extracurricular activities, especially the lucrative promotional deals they arranged.

He believed he was representing America, not himself.

But he wasn't completely above the hype. When Field Enterprises signed

the astronauts to tout the World Book Encyclopedia, Elliot was on

board. Friend Bob opposed buying the costly books for his family,

despite his wife's entreaties, until Elliot showed him a set. Then Bob

gave in.

With his children in school and job in hand, Bob again found time for

flying. After razzing Elliot for years about his crackup, he finally

had one of his own. It happened while he was doing touch-and-gos with

an instructor to get his twin-engine rating.

As one of the tests, Bob reduced throttle to "feather" the propeller.

The engine conked out and wouldn't restart. While Bob tried to rev it

and the instructor argued with the control tower, neither saw the

ground rushing up.

They plowed into a suburban Southern California home. The instructor

received minor injuries, and Bob's secretary, in the back seat, was

thrown clear with a scratch. Bob broke a foot and a few vertebrae, but

he was sound enough to tell rescuers to shut down the plane before it

caught fire.

He was in a cast for months, but was back at work in weeks. After all,

he had crashed on company time. But the worst blow came when the FAA

noted his arm and made him recertify himself, though he had logged

countless hours. He was furious at this comment on his competence.

Sadly, Elliot wasn't there to enjoy Bob's plight. Three years earlier,

in 1966, he and astronaut Charlie Bassett had flown a T-38 trainer to

St. Louis to use a simulator. They never touched ground. Perhaps

cutting it close one time too many, Elliot caught a wingtip on a

building's roof. The jet exploded and both men died instantly.

Elliot had served as backup on Gemini 5 with Neil Armstrong. He was

Capcom on Gemini 6 and 7, relaying instructions to the men in orbit.

In one case he solved a glitch with their fuel cells, his pride and

joy, himself. The public became familiar with his cool, calm voice.

Elliot had served as backup on Gemini 5 with Neil Armstrong. He was

Capcom on Gemini 6 and 7, relaying instructions to the men in orbit.

In one case he solved a glitch with their fuel cells, his pride and

joy, himself. The public became familiar with his cool, calm voice.

When a reporter asked Armstrong why Elliot wasn't joining him in Gemini

8, Neil replied, "Elliot's too good a pilot not to have a command of

his own." Indeed, Elliot and Bassett were scheduled to fly in Gemini 9--which ironically was in the building they hit. Instead, backups

Thomas Stafford and Eugene Cernan took their place. The duo went on to

circle the moon in Apollo 10, and Cernan was the last man to tread it

in Apollo 17.

Elliot was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with his fellow

astronauts as pallbearers. His Merchant Marine colleagues especially

felt the loss. He had won an award as one of the Academy's three

outstanding graduates. The school renamed its chapel after him, a

fitting tribute.

Years later, Bob retired after a couple of heart attacks ended a

successful career. His only regret was being grounded by his medical

condition. Though it seemed hopeless, he insisted he still could fly.

He vowed to fight the restriction all the way to the top.

The papers were on his desk when he died in his sleep in 1990. Friends

eulogized him as a can-do pragmatist and puncturer of balloons. As the

minister noted, the closest Bob came to religion was when he flew. His

ashes were scattered over the ocean--from an airplane, of course.

Now Bob and Elliot are both phantom pilots, but their influence lives

on. Bob's wife and second son took enough lessons to fly solo, and

several of Bob's pals learned to fly as well. One is building a plane

from a kit.

As for Bob's first son, he's firmly rooted to earth. But he remembers

meeting Elliot See as a child and enthusing about the stars, as if

astronomers and astronauts were the same. (Elliot, ever the trouper,

no doubt listened earnestly and encouraged the boy's dreams.) And

though the son doesn't fly, he writes about it sometimes, and lets his

imagination soar.

###

Copyright (c) 1998 by Robert Schmidt. All rights reserved.

En route to the skies, Bob

Schmidt and Elliot M. See Jr. made some earthly stopovers to get educated, including The U.S. Marine Academy, Stanford University and Harvard. Elliot's engineer-father, who worked for GE's Aircraft Division, imbued his son with a love of all things technical. As an astronaut, Elliot came within inches of living out his dream and Bob's: to journey into space.

Elliot had never given much thought to flying, but Bob infected him

with the bug. Soon, Elliot's passion for it was as feverish as Bob's.

Elliot took lessons and bought a Luscombe Silvair, the first all-aluminum plane, with Ray. They flew the small two-seater around Ohio

incessantly.

Elliot had never given much thought to flying, but Bob infected him

with the bug. Soon, Elliot's passion for it was as feverish as Bob's.

Elliot took lessons and bought a Luscombe Silvair, the first all-aluminum plane, with Ray. They flew the small two-seater around Ohio

incessantly.

Endless Flights:

Endless Flights: Elliot had served as backup on Gemini 5 with Neil Armstrong. He was

Capcom on Gemini 6 and 7, relaying instructions to the men in orbit.

In one case he solved a glitch with their fuel cells, his pride and

joy, himself. The public became familiar with his cool, calm voice.

Elliot had served as backup on Gemini 5 with Neil Armstrong. He was

Capcom on Gemini 6 and 7, relaying instructions to the men in orbit.

In one case he solved a glitch with their fuel cells, his pride and

joy, himself. The public became familiar with his cool, calm voice.